Although the fund paid out close to R28-billion to employees and employers for April and May, the labour department said in a statement that nearly 970 000 employees had not received their Ters payments. (Ntswe Mokoena)

Labour Minister Thulas Nxesi has painted a bleak picture of the financial threat posed by growing joblessness to the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF).

In a reply to a Democratic Alliance question in Parliament, Nxesi warned that the fund would become “financially unsound” in the event of continuing heavy job losses.

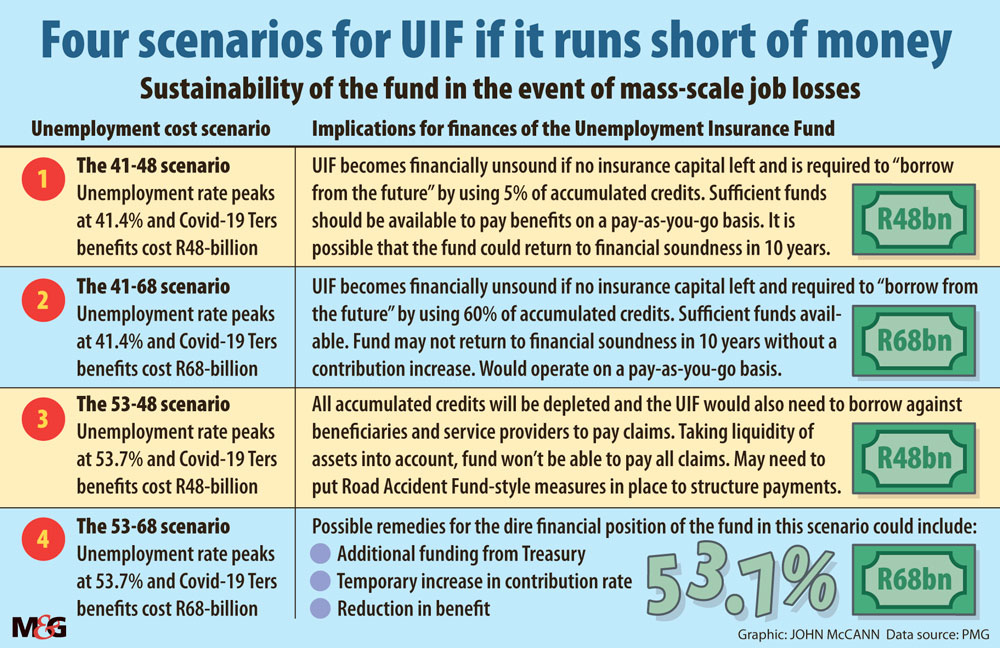

Surging unemployment will have the dual effect of reducing the fund’s income and placing new demands on it for payouts. The minister set out four scenarios of the UIF’s growing financial weakness and reliance on external funding if joblessness rises beyond the 41% mark.

He said the fund would initially be forced to tuck into its accumulated credits.

These currently stand at R41-billion, according to the UIF board’s actuarial findings on the effect of Covid-19 on the fund’s financial sustainability.

Once the joblessness rate rose beyond 51%, Nxesi warned that the UIF would have to go cap in hand to the treasury.

This would not be without precedent: the treasury bailed out the fund in the late 1990s. But the labour department’s director general, Thobile Lamati, told the Mail & Guardian that going to the treasury for additional funds “would not be ideal this time round” because of current constraints on the fiscus.

Lamati said the labour department had projected that an additional 1.5-million South Africans could be unemployed because of the pandemic and the lockdown and that “a number of small companies are going to be in financial distress”.He insisted that despite this, the fund would be in a position to cushion employees who may now be laid off.

The unemployment rate hit a record 30% in the first quarter of 2020, before the economic effect of the Covid-19 pandemic was felt.

The economy is expected to undergo further contraction. Highlighting the need to breathe new life into the economy, the treasury’s supplementary budget projected that gross domestic product will fall by 7% this year, while

the South African Reserve Bank expects a slightly higher contraction of 7.2%.

In its annual report, released on June 29, the reserve bank notes that the country’s near-term outlook depends on how the Covid-19 pandemic develops and the extent of restrictions placed on business activity in an effort to contain the virus.

Since April, the UIF has been providing short-term financial support for employees whose income has been hit by the pandemic and the lockdown in terms of the Temporary Employer/Employee Relief Scheme (Ters).

The scheme covers only a portion of employees’ salaries. The average monthly payment is R6 000, with the minimum R3 500. Ters came to an end this week. But the UIF has not yet met all its financial obligations to claimants under the scheme. The

fund has experienced some “technical glitches” regarding the June claims, according to a statement by UIF commissioner Teboho Maruping.

The UIF’s spokesperson, Makhosonke Buthelezi, revealed this week that the fund has been selling assets to make Ters payouts.

In May, Lamati told Parliament’s labour committee that the fund had set aside R80-billion to deal with the possible mass retrenchments as a result of Covid-19. The UIF had R40-billion set aside for contingency operations, which would cover three months without liquidity.

As the lockdown could extend beyond three months, there would potentially be a need to sell government bonds to continue operating.

In his first scenario, Nxesi told Parliament that if the unemployment rate reaches 41.4%, the UIF will have to “borrow against future earnings” by using 5% of its accumulated funds to meet the new demand for unemployment support.

In this scenario, Covid-19 benefits would cost the fund R48-billion and it would be left without any “insurance capital” to fall back on.

In this scenario, beneficiaries would be paid out on a “pay-as-you-go basis”. The fund was expected to make up its losses over 10 years.

The second scenario also foresees unemployment rising to 41.4%, but with benefit payouts ballooning to R68-billion. In this situation, the UIF would have to borrow from the future by using 60% of its accumulated credits.

Sufficient funds would still be available, but Nxesi said: “It is unlikely that the fund could return to financial soundness in 10 years without a contribution increase. [It] will essentially operate on a pay-as-you-go basis.”.

The third and fourth scenarios forecast unemployment reaching 53.7%.

In scenario three, the UIF would have to pay out R48-billion in Covid-related benefits, depleting its accumulated credits and forcing it to borrow from beneficiaries and service providers to pay claims.

“Taking liquidity of assets into account, the fund will not be able to pay all claims when due and may need to put [road accident fund]-style measures in place to prioritise/structure payments.”

In the fourth scenario the UIF could be required to make Covid-related payments of R68-billion. To make up for the losses, the UIF would have to source funding from the treasury. It could also introduce a temporary increase in the contribution rate of companies and workers, or it could cut benefit payouts.

June 30 was the deadline for the lodging of Ters claims, because the scheme was intended to pay out for three months per applicant.

But the UIF still has to meet major unprocessed demands from the scheme. Some companies and employees have not yet received their claims for May because payments were stopped for three days after the UIF detected fraud.

Buthelezi insisted that the fund has caught up on claims that were not processed in time. But he conceded that “you may still have instances where some delays are experienced on certain applications”.

A recent survey of 40 000 businesses by Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies, Business Unity South Africa and the Manufacturing Circle found that most businesses will be forced to retrench people once the Ters benefits come to an end.

This was despite greater economic activity being permitted since June 1, when South Africa transitioned from level 4 to level 3 of the lockdown.

Only four companies said they had retrenched before the move to level. But almost half had required employees to accept lower pay, and more than a third said they would most likely lay off workers once the Ters grants end.

Most companies also noted that while the economy had opened up following the hard lockdown, demand for goods and services was still low. The cost of reopening under level 3 has also increased, because businesses are required to introduce new measures to curb the spread of the virus.

Although the fund paid out close to R28-billion to employees and employers for April and May, the labour department said in a statement that nearly 970 000 employees had not received their Ters payments. That amounts to about R4-million in unpaid benefits.

Thando Maeko is an Adamela Trust business reporter at the Mail & Guardian