Unsustainable debt: SAA workers striking for higher wages. Compensation for state employees accounts for 37% of national consolidated expenditure. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

As the country grapples with the disastrous effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on its frail economy, the risk posed by inefficient state-owned enterprises (SOEs) has been significantly enhanced. Put together, the state guarantees R385-billion in debt for these entities.

With alarm bells sounding at state arms manufacturer Denel, state broadcaster the SABC, and SAA — and with power utility Eskom still in intensive care — commentators and big business have called for a review and realignment of the role played by SOEs in the economy.

This includes an improvement of management and governance, cost cutting, the elimination of waste and corruption, and an end to the political interference.

Business leader Martin Kingston, who has experience in both the private and public sectors, believes part of the problem is that the government, as the shareholder in SOEs, often becomes over-involved in strategic, operational and accountability structures in these entities.

This anomaly, he added, is rarely found in the private sector, but allows other agendas to dictate operations at SOEs. “When you’ve got a board at a state-owned company, and it’s got certain fiduciary responsibilities, it must be left alone to discharge them,” he said.

“What you often find is that the board takes decisions on how it will achieve key objectives, and who it will involve and hold accountable, but these efforts are undermined by the shareholder representatives, who often have different goals,” he said, adding that it was ultimately the boards who take accountability for the performance of the entity.

Kingston is part of the Business for South Africa initiative, a collective that has brought together different bodies representing business to respond to the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Earlier this month, the body released a 111-page document detailing its proposals to rescue the South African economy.

Released two weeks ago, the document, titled “Post Covid-19: A new inclusive economic future for South Africa”, presents an accelerated economic recovery plan that identifies SOEs as a risk and calls for an “urgent” review of all SOEs, with a view to rationalise them and decisively address those that do not add discernible value.

SOEs, the organisation said, generate an average return on equity — a measure of efficiency that is calculated from profitability in relation to the cash it gets from its shareholders — of less than 0.2%. This average is well below the 5% their peers in other emerging markets generate.

To illustrate the risk these entities pose to the economy, their government-guaranteed debt, at R385-billion, is more than a third of the state’s R980-billion contingent liabilities. In the case of SOEs, this refers to money the government would have to pay, given a future event such as a cross-default.

“As Business for SA, we’ve said if we’re going to recover from the economic damage of Covid-19, we need to put in place an aggressive economic strategy that will deal with the issue of SOEs and render them efficient and, if that cannot happen, they need to be responsibly migrated off the government’s balance sheet,” Kingston said.

Democratic Alliance MP Alf Lees, who heavily criticised the creation of an SAA 2.0 that will cost the taxpayer R26-billion, said the airline was an example of a programme by the ANC to create unnecessary, high-paying jobs in the SOEs for cadres.

“Once the ANC had created the hundreds and thousands of unsustainable jobs, it has made it possible for the trade unions and Cosatu to hold the ANC to ransom: both to force them to increase salaries way above market rates and to prevent the elimination of the unsustainable jobs,” he said.

“This has certainly been the case at SAA, where the employee numbers ballooned to a point that, by international standards, SAA had at least 30% too many employees and which has contributed considerably to the massive losses.”

Kingston’s last assignment in the public sector was on the board of SAA; he resigned just after the company was thrust into business rescue last November.

The airline is no stranger to shareholder interference: the most recent example is the resignation of former chief executive Vuyani Jarana.

At the time of his departure, SAA’s turnaround strategy, which included restructuring that would have led to job losses, was approved, but efforts to implement were being second-guessed and hampered by the shareholder. In his resignation letter, Jarana said the lines of accountability between himself, the board and the shareholder were blurred and affected his work.

Jarana resigned a couple of days after Eskom announced the resignation of Phakamani Hadebe as its chief executive.

Hadebe has remained silent about his reasons for calling it quits, but there has been speculation he was frustrated by his shareholder minister — Public Enterprises Pravin Gordhan — becoming too involved in operations at the power utility, which was experiencing a particularly bad period of load-shedding.

Two weeks ago, Denel became the latest SOE under Gordhan to announce the resignation of its chief executive, in this case, Danie du Toit. His resignation is attributed to his loss of confidence that Denel — which is in the process of selling off some of its divisions — can be saved.

This is after the government failed to deliver on funding needed to restart operations and deliver on R14-billion worth of orders.

In his February budget, Finance Minister Tito Mboweni promised R576-million, to Denel but it has been reported that only R72-million has been paid to date. Denel runs the risk of incurring penalties and returning advance payments should orders be cancelled.

Gordhan’s spokesperson Sam Mkokeli dismissed suggestions the minister was too involved in operations in entities under watch.

“The department is on a path of restructuring the seven entities under its mandate to improve governance, operational efficiencies and place them on a sound financial footing,” he said.

“Our entities have a clear mandate to minimise job losses but without compromising the pressing need to create commercially viable and dynamic organisations that can stand on the strengths of their balance sheets. Their own revenue must match or exceed the costs.”

On top of troubled SOEs, the treasury, together with the department of public service and administration, is deadlocked with public-sector unions over implementation of year three of the multi-year wage agreement signed in 2018.

In papers filed as part of an urgent labour court application by the government to postpone bargaining- council proceedings, the state says it does not have the R35-billion needed to implement the agreement. The application was dismissed.

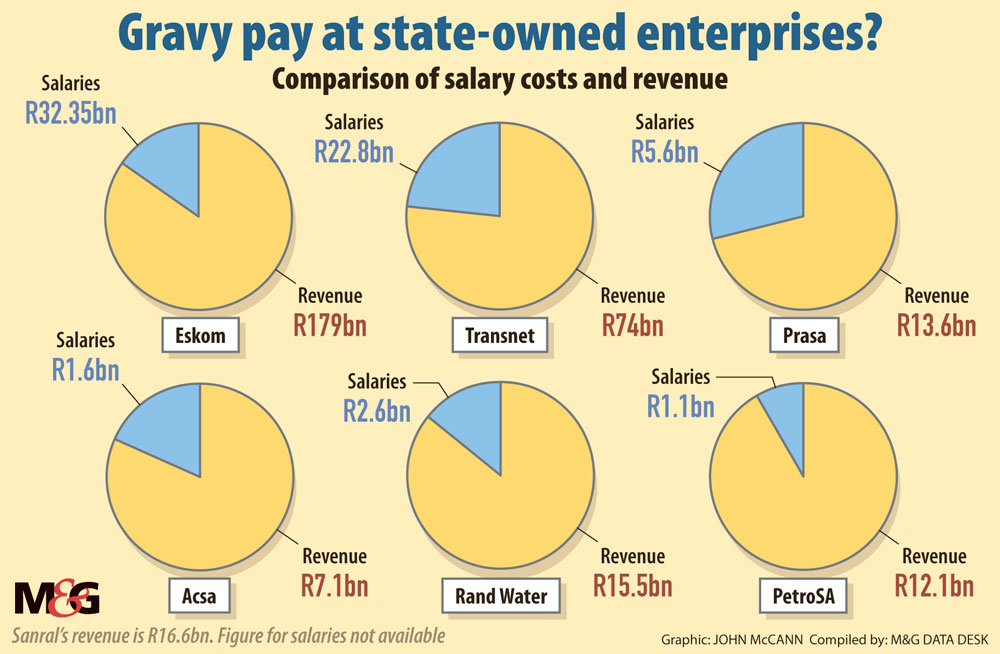

Cosatu spokesperson Sizwe Pamla said the government had only itself to blame for allowing compensation of state employees to reach 37% of its consolidated national expenditure. He also pointed a finger at SOEs, saying they received bailouts over and above money they wasted on high salaries and consultants.

“They don’t seem to be bothered about the messy pay and benefits structures within the vast plethora of agencies and public entities that contribute to … the spending on remuneration,” Pamla said.

Economist Xhanti Payi said political interference in SOEs is unavoidable because the government owns them, but stressed that it needed to be strategic and geared towards helping SOEs compete.

“I get the sense that the public itself — if Twitter and radio callers represent the public — actually wants the interference, because they feel the government must play a role in these entities in order that the public benefits,” Payi said.

“It’s the same reason we want a black bank. Somehow, we hope a government-owned entity will deliver what the private sector denies us. This is why the opposition is so strong [on] privatisation, but want the government to interfere so as to save jobs and create opportunities.