Polluters: Schonland coal mine in eMalahleni local municipality in Mpumalanga. The province, as well as the Free state and Limpopo, have the least clean development projects. (Wikus De Wet/AFP/Getty Images)

South Africa’s carbon tax laws are set to change with the international frameworks it aligns to, as reflected in the latest amendment to the carbon offset regulations.

The amendment is linked to the Kyoto Protocol, an international agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which expired last year when the Paris Agreement came into effect.

The treasury said the outcome of the negotiations at COP26 [Conference of Parties] in Glasgow starting on 31 October on these issues would inform amendments to the carbon tax regulations in the 2022-23 budget statement.

In the meantime, amendments to the offset regulations published on 8 July already provide clarity on allowing big carbon emitting industries in South Africa to carry their old credits into the inconclusive new rules that will govern the new system.

The treasury “in collaboration with the department of environmental affairs, forestry and fisheries and [the department of] mineral resources and energy will consider a possible expansion of the carbon offset mechanism to include offset projects developed outside South Africa including at a regional level. Any further announcements on the scope of the offset mechanism will be made in the budget 2022-23,” the treasury said.

The treasury said the offset projects and credits were tied to international standards with robust verification systems. It added that it would ensure the environmental integrity of the carbon offset allowance mechanism and limit the potential for fraudulent credits to be used for purposes of the carbon offset allowance.

These international agreements give rise to specific ways in which developing and poor countries can lower greenhouse gas emissions by way of financial support from big emitting countries and multinationals — who then use that investment as a credit towards their efforts to stop the acceleration of climate change

Sometimes they trade this credit in the carbon market.

South Africa’s offset regulations under the Carbon Tax Act (2019) govern how companies can use the credits they get from supporting climate efforts — for example renewable energy projects — for these tax allowances.

Under the Kyoto Protocol, a clean development mechanism (CDM), allowed emission-reduction projects in developing countries to earn certified emission reduction credits. Parties at the UN climate talks, or COP, are yet to finalise the transition of the clean development mechanism under the Paris Agreement, which marked the end of the old agreement on 31 December last year.

Talks on this were delayed when COP26 was postponed last year because of the Covid-19 pandemic. A committee has put temporary rules in place and requests for credits continue in the absence of a framework.

That committee took a decision to make all credits under the transition phase of these rules provisional, which means it carries the risk of not getting certified once the new rules are final. A meeting about this and other dilemmas is set for November.

The committee said the clean development mechanism incentive has led to registration of more than 8 100 projects and programmes in 111 countries — from renewable energy projects to large industrial gas projects. To date, more than two billion certified emission reduction credits have been issued, a token of the amount of greenhouse gas that was avoided or reduced by the clean development mechanism.

The transfer of credits under the old protocol is a bone of contention at COP negotiation level. India, Australia and Brazil want a new system that will allow countries to use unspent old credits from Kyoto, as well as the double counting of emissions reductions and trading of Kyoto-era credits, creating a loophole.

In South Africa it would mean Sasol selling its credits in a carbon market to another emitter and then counts that credit towards its own mitigation targets. The July amendments to the country’s carbon offset regulations will already allow a company such as Eskom to transfer its unused credit allowances to the new system.

COP25 in 2019 ended with a draft text that suggested the old credits be counted until 2025, a move opposed by some countries because it will further delay more ambitious support for developing countries to mitigate climate change while they are burdened with extreme weather and other effects.

Olivia Rumble, the executive director at Climate Legal, said South Africa’s offset regulations were very clear on how long offsets are eligible.

“The Offset Regulations (as amended) prescribe that vintage offsets created up until July 2019 will only be eligible up until the end of next year,” she said, adding that the offset scheme had numerous benefits for people in South Africa.

“Offsets have the benefit of reducing a taxpayer’s liability, by enabling additional greenhouse gas emission reductions where taxpayers for technical or other reasons may not have otherwise been able to implement reductions on site, or at least do so cost effectively,” she said.

“Offset projects deliver least cost emission reductions but they also generally tend to have broader co-benefits. These benefits, as identified by the government, include the channelling of capital to rural development projects, creating employment, restoring landscapes, reducing land degradation, protecting biodiversity, and encouraging energy efficiency and low carbon growth.”

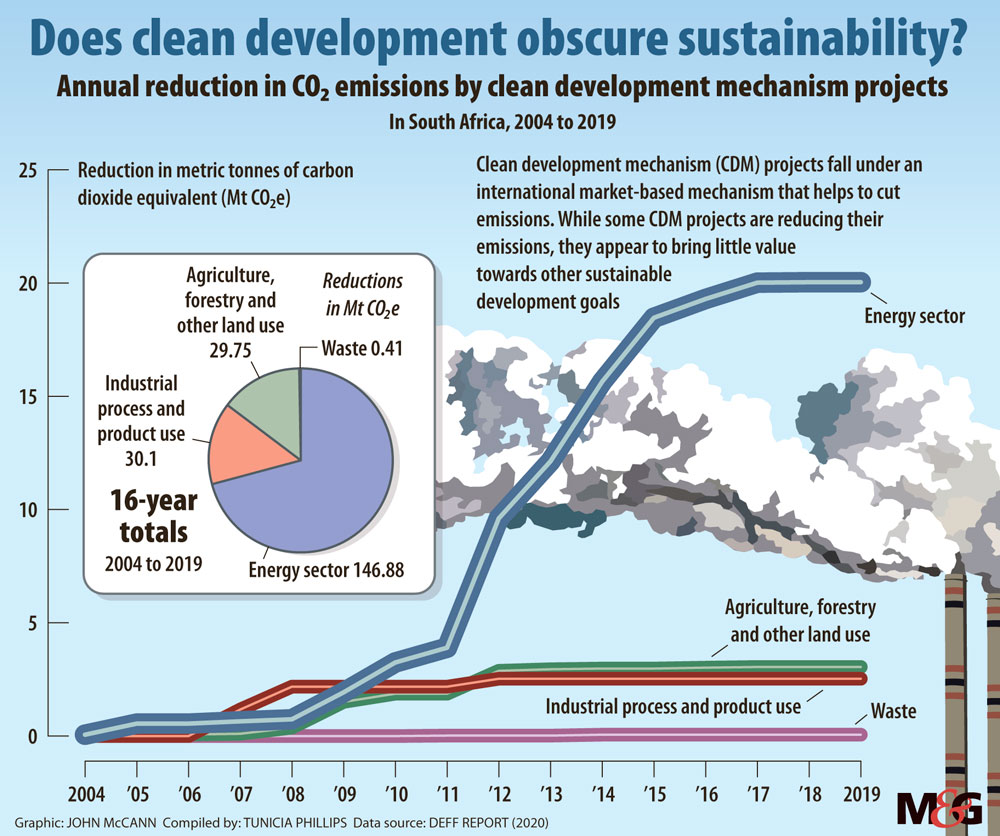

Researchers have questioned whether offset projects under the old mechanism have contributed to sustainable development in South Africa since it adopted the clean development mechanism in 2005. The data showed that the mechanism has contributed to emission reductions but has shown little value for social development and people.

“Given the uneven distribution of CDM (clean development mechanism) projects across countries and regions and the fact that a few technologies and sectors have dominated in the early stages of CDM, the question to be asked is whether CDM has fallen short in contributing to sustainable development in South Africa,” said the authors of an article in the International Business & Economics Research Journal, titled The Impact Of Clean Development Mechanism Projects On Sustainable Development In South Africa.

The United Nations Environment Programme found that clean development mechanism projects were particularly unevenly distributed in South Africa, with the majority of projects happening in the Gauteng and Eastern Cape provinces — 50% of all clean development mechanism projects.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

The Free State, Limpopo and Mpumalanga have the least — 18.9% — of the total number of clean development mechanism projects despite being hubs for at-risk assets such as coal.

In the clean development mechanism study, direct benefits to people such as employment and direct social and environmental benefits were low.

“The overall analysis of CDM’s impact on sustainable development reveals that South African projects are focused on greenhouse gas reductions to the detriment of welfare and economic considerations,” the researchers concluded.

The UN secretary’s office also cautioned countries about the authenticity of certificates for credits given to projects with little value for people. “All organisations should exercise appropriate caution and undertake adequate due diligence when dealing with or engaging in business with individuals claiming affiliation to or specific status with respect to the UNFCCC and the CDM,” the office said. It later said fraudsters were arranging uncertified and unrecognised CDM investments under the pretence of being from the UN climate body.

Labour unions have warned that people living in South Africa’s coal areas are set to be hardest hit if the country’s shift to a low-carbon economy is poorly managed. The unequal and poor distribution of development projects under global treaty commitments shows that the country has not focused on transition development initiatives for vulnerable communities who are reliant on and built around fossil fuel investments that are increasingly growing in risk.

Tunicia Phillips is a climate and economic justice reporting fellow with the Adamela Trust, funded by the Open Society Foundation for South Africa