President-Kassym-Jomart-Tokayev. (Kazakhstan President Press Office/TA

In recent weeks, Kazakhstan’s president Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has taken a stand against inequality.

Addressing the country after days of protests that were suppressed by mass police brutality, he acknowledged the wave of popular anger against his predecessor, long-ruling strongman Nursultan Nazarbayev.

“Thanks to the first president,” he said, “in the country there appeared a group of very profitable companies and a group of people who are rich even by international standards. I think it’s time to pay back the people of Kazakhstan.”

Until the wave of protest and violence shook Kazakhstan in early January, even this mild public criticism of Nazarbayev would have been unthinkable. But Tokayev appeared to have gotten the message that the people of Kazakhstan wanted a change after decades of oil-fuelled oligarchy. He promised to make it happen.

“As head of government, I will continue the policy of political transformation and modernisation of our society,” he said.

As it turns out, Tokayev’s family had secretive wealth, safely stored in Europe, as far back as 1998 — when nearly half of Kazakhstan’s population lived under the poverty line. A leak of banking data from Credit Suisse shows that a Swiss bank account for Tokayev’s then-wife Nadezhda and 14-year-old son Timur was opened that year, even as Timur attended an expensive boarding school in Geneva.

It’s unknown how much money passed through the account over the years. According to the Swiss leak, it reached its maximum value of Sf1.5-million ($1 million) in 2005.

Documents from an offshore services provider, corporate files and property records all show that, in the years to come, the family continued to accumulate significant wealth outside Kazakhstan. In 2012 — after the Swiss account was closed — the Tokayevs opened offshore companies in the British Virgin Islands that had their own bank accounts in Switzerland and controlled a UK company with $5-million in assets at one point in 2014. They also amassed properties in Moscow and Geneva worth at least $7.7-million.

During those years, Tokayev held a series of senior government positions, including minister of foreign affairs, prime minister and senate chair. Neither he nor his wife had any known businesses or sources of wealth. Only their son Timur has ever been connected to any real business — and even that deserves considerable scrutiny. As reported by Kazakh media, he was listed as the co-owner of an oil company that won lucrative development rights to a Kazakh oil field, and later earned millions in profits, at just 18 years old.

Timur may also be the family’s original connection to Switzerland. It recently emerged that he attended College du Leman, one of Geneva’s most expensive boarding schools, and also has a diploma from the US-accredited Webster University branch in Geneva.

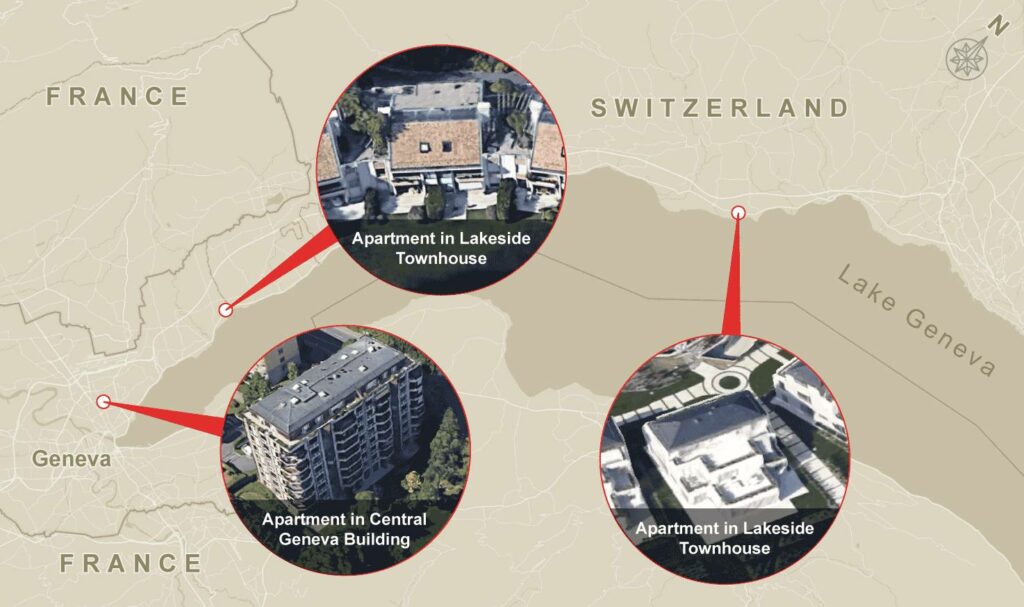

The Tokayevs also made property acquisitions in and around Geneva, all in Timur’s name: an apartment in a quiet district in the city, an apartment in a lakeside townhouse in the nearby municipality of Versoix, and another townhouse apartment in the village of Saint-Prex.

Timur Tokayev’s properties in Geneva. (Edin Pasovic / Google Earth)

Timur Tokayev’s properties in Geneva. (Edin Pasovic / Google Earth)

It is unknown how long Timur spent in Geneva after graduating, but his father did live in the area while he was serving as director general of the UN Geneva office in between 2011 and 2013.

Meanwhile, Timur had moved on to Moscow, reportedly cruising around the Russian capital in a Lexus and BMW with diplomatic plates and receiving an advanced degree from the diplomatic academy of the Russian foreign ministry.

He and his mother also acquired several expensive apartments in Moscow. Curiously, as an investigation by now-imprisoned Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny showed, the Russian government appears to have wiped any mention of them from Russian property records. (Navalny’s team discovered the Tokayevs’ ownership from records they had downloaded before they were deleted from the registry.)

Some of their real estate has since been sold. Their remaining Moscow properties include a large apartment in an elite downtown residence called Fusion Park, and another large, two-floor apartment 2km from the Kremlin. Tokayeva was also registered at a third apartment in the city’s northwest.

The Fusion Park apartment complex in Moscow where Timur Tokayev has an apartment. (Google Street View)

The Fusion Park apartment complex in Moscow where Timur Tokayev has an apartment. (Google Street View)

The Tokayevs’ secrets also extend outside of Europe. Thanks to documents from the Pandora Papers — a trove of files from offshore service providers that were shared with OCCRP by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists — reporters were able to trace their activities to the British Virgin Islands, a jurisdiction used by wealthy people around the world to secretly hold their assets.

In 2012, the year after the Tokayevs’ Credit Suisse account was closed, the family established two offshore companies in the British Virgin Islands. The companies — Wishing Well Group, owned by Tokayev’s former wife, and Wisdom Invest & Finance, owned by Timur — appear to be corporate vehicles created for the purpose of owning a UK company called Edelweiss Resources. (Records also indicate that each of these shell companies also held its own Swiss bank account.)

Because Edelweiss has filed only abbreviated financial statements, little is known about its activities. But its latest filing from March 2014 does show that it had just more than $4-million cash in the bank and nearly $1-million in investments that year.

The same summer, the Tokayevs took another step to hide their investments even more deeply. A Cyprus registration agent involved in the formation of their companies asked its British Virgin Islands office to remove the Tokayevs as shareholders and replace them with nominee or proxy shareholders that would effectively hide their ownership. The request came in an email leaked in the Pandora Papers. The three Tokayev companies have since been shut down.

Kazakhstani officials are not obliged to make public their asset declarations, leaving the source of the Tokayevs’ millions a mystery. The family did not respond to requests for comment.

In response to inquiries from OCCRP and Süddeutsche Zeitung, Credit Suisse said it could not comment on individual client relationships and rejected “allegations and inferences about [its] purported business practices.” (Click here to read the bank’s full response to the Suisse Secrets project).

Research on this story was provided by OCCRP ID. Data expertise was provided by OCCRP’s Data Team. Fact-checking was provided by the OCCRP Fact-Checking Desk. This story was originally published by the OCCRP.