A logo of Naspers Ltd. sits on the side of the headquarters of the Media24 Ltd. building in Cape Town, South Africa. (Graeme Williams/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Ask someone in a bookshop or a pub or even a newsroom what Naspers is, chances are they’ll say: a media company. Dead wrong. Going by this year’s annual results, and the half decade before, you’d be closer if you’d called it something like Uber Eats or Gumtree or Paypal or Facebook. Or all of those in one.

Fair enough, the “pers” in Naspers does not stand for purple, it refers to the company’s newsprint roots. And sure, Media24 — owner of Beeld, Rapport, News24 and City Press — is still part of the business, but by now it’s so small compared to the rest, that classifying Naspers as a media group would be like referring to your iPhone as an abacus, just because it has a calculator built-in.

Many South Africans — most of them investors in one way or another through the large holdings the government and private pension funds have in Naspers — have no idea what the largest company on the JSE is doing. (Ask a feisty analyst, and he or she would say, neither does the company’s management.)

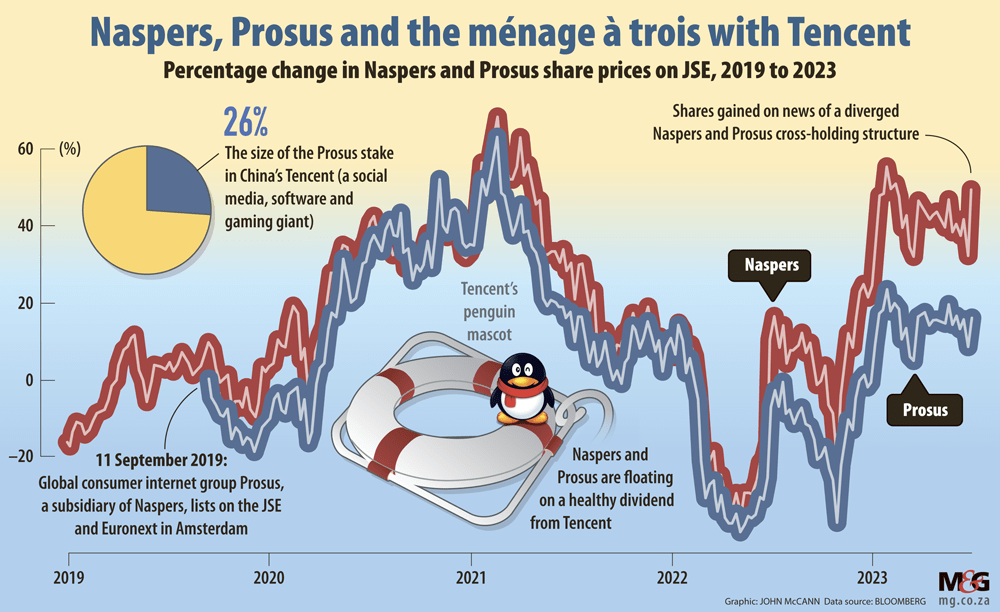

Naspers likes to style itself as a consumer-facing technology group. Through its Amsterdam-based subsidiary Prosus, it holds a sprawling portfolio of businesses in food delivery, education technology, electronic classifieds, online payments and e-tail. Of course, it also has a 26% stake in China’s Tencent, a well-timed investment that was made more than two decades ago when Koos Bekker was at the helm.

Tencent, which dabbles in anything from social media and online games to productivity tools, has this year again paid a handsome dividend. And that’s a lucky thing, because, apart from Tencent, most of the rest of Naspers and Prosus are making losses.

Sounds concerning, doesn’t it? Losses with a capital L. The same L you see in the back window of a car you don’t want to be behind. Still learning. Still getting the hang of the machine.

And Naspers is a complex machine. Not only to steer, but to understand.

That’s why much time in results presentations and many pages of annual reports are spent on trying to explain how it all fits together.

Just about every year, the company’s management also announces a new move aimed at simplifying the structure. See, after a previous round of simplification, Naspers and Prosus ended up holding substantial stakes in each other. This came about as a result of a share swop that was meant to unlock value. Now, if you’re confused, don’t worry, you’re not alone.

“Shareholders didn’t like this cross-holding, they found it too complex and difficult to understand,” said Naspers and Prosus’ chief financial officer Basil Sgourdos.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

This time around, management announced that it would unwind the cross-holding.

The mechanics of this involves a capitalisation issue of shares in which Prosus and Naspers will not participate. Importantly, it will not affect control; Naspers will still be the holding company with 72% of the votes in Prosus.

The markets have welcomed the move to a simpler structure, with Naspers shares holding on to its 10% gain in the week since the announcement and Prosus advancing 7%.

Analysts like it too, but caution against giving chief executive Bob van Dijk and Sgourdos too much credit. It is worth remembering that the cross-shareholding complication is something that was introduced by the current management team not so long ago, according to Argon Asset Management equity analyst Ian Brink.

The move also allows the group to continue with its other priority — buying back shares. Last year, Prosus embarked on an “open-ended” buyback scheme.

Basically, it would sell shares in Tencent and use the money to buy back its own shares. At the same time, Naspers was selling Prosus stock to buy Naspers shares.

Why would you buy your own shares? Well, because they are cheap. Or more accurately, they are not an accurate reflection of their true value. This is where the D-word comes in.

For years Naspers and Prosus, since its listing in 2019, have struggled with a discount to the value of its stake in Tencent. It is easy to see what Tencent is worth, because it is traded on the stock exchange in Hong Kong. But Naspers and Prosus are quoted at much less, which in effect means that the market ascribes a negative value to the rest of its portfolio of e-commerce assets.

So, both companies have been buying back shares, boosting their own share price and narrowing the discount by more than 15 percentage points in the process.

“I think it’s the hammer approach to fixing the discount problem — buying back shares arithmetically should reduce the discount. There are however no guarantees that that narrowing will persist after the share buybacks stop — and they have to stop at some point,” adds Brink.

But for now, the unwinding of the cross-holding would allow buybacks to continue unencumbered, Sgourdos said.

Meanwhile, Prosus is trying hard to get the rest of its assets to profitability, setting 2025 as a target date.

The latest numbers show that on a full-year basis losses have increased, but they seem to have peaked in the first six months, according to All Weather Capital equity analyst Jarred Houston. Revenue has grown in all of these segments and the path to profitability seems clearer.

Importantly, management is also heavily incentivised to get food delivery, payments, e-classifieds and edtech to stand on its own feet.

“It is harder to ascribe a negative value to something that actually turns a profit,” Houston adds.

Brink thinks they might meet the aggregate profitability of e-commerce target even sooner than the first half of 2025.

The big cheque book has also been holstered.

Capital allocation has been poor historically and they have overpaid for assets, says Brink. “There does seem to be a more disciplined approach to capital allocation now.”

Houston echoes this sentiment.

“Prosus is not going after large new acquisitions anymore, but investing in the businesses that it already owns. The group’s strategy is now more focused on smaller bolt-on transactions that could increase the profitability of the existing businesses,” he says.

For now, Prosus and Naspers are being carried by the Tencent dividend and share sales.

Ironically, a tiny part of Naspers did turn a profit last year. Media24 chipped in with $7 million. Not much out of a $3.3 billion profit on an equity accounted basis. But a trading profit nevertheless.