Teachers need to move beyond asking learners to memorise information to being able to ask meaningful questions and work together on real-world problems.

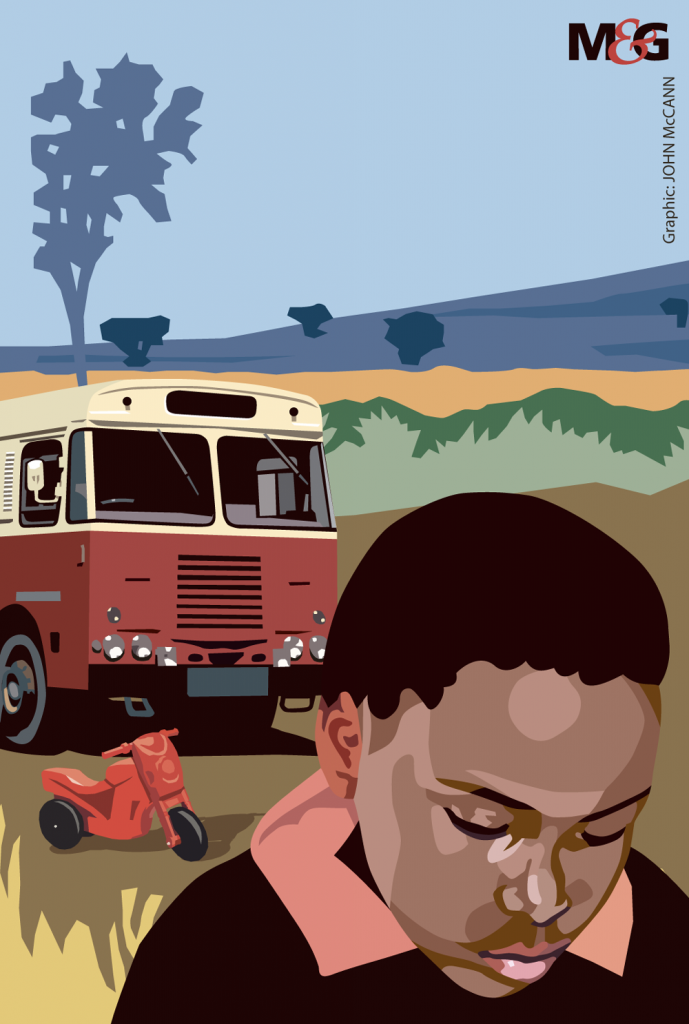

Phindulo Rahlapane swooshes around the yard on his plastic motorcycle. His Aunt Mavis Ndou (47) watches as the eight-year-old tucks in his knees below the handle to enjoy the speed he has built up.

Moments later, he abandons the motorcycle and turns his attention to the unfamiliar person speaking to his aunt. The stranger greets him, he answers with a bright smile and walks to the little play area he’s put together for himself.

Phindulo is joined by his friend, Rotondwa, from next door. Armed with an empty tin, Phindulo carefully adds water into his can and uses a twig to stir it. Rotondwa follows his lead.

U bika matope; he is cooking pap — only this one is made of mud instead of mealie meal.This is a popular make-believe game many children in Venda grow up playing. There are no squabbles between the two companions, nor are there words. The silence is filled with glances, smiles and Phindulo’s guiding hands.

Phindulo is non-verbal and has a severe intellectual disability. He communicates using facial expressions, eye contact and other gestures that his family and friends decode. He enjoys cooking “pap” in his makeshift kitchen and riding his scooter. These are his favourite past times, and sometimes, his only.

Phindulo has never attended school, but he used to go to a creche until September. The creche is not an official early childhood development (ECD) centre, a government programme specifically designed to protect the rights of children under the age of five to develop their full cognitive, emotional, social and physical potential. Mavis says it caters for people of all ages with disabilities.

In April, the department of basic education took over the ECD centres from the department of social development. But the positive effect of the migration hasn’t reached Vhembe, in Limpopo, where Phindulo lives with his family.

According to the nonprofit Grow Educare, “Failure of municipalities to implement their legislative mandate, charging unaffordable fees for zoning land, high service changes and delays in issuing municipal documents required for ECD registration and children with disabilities are not adequately provided for.”

Children from impoverished areas are the most affected by the difficulties facing ECD centres, with children living with disabilities facing a double burden.

Back to school is not a reality

“I want to go to school,” says 12-year-old Israel Masindi, who has a severe intellectual disability. “It hurts me when I see other kids going to school.”

He attended Tswinga Primary School, a mainstream school in the Vhembe district, for six years. He lives with his grandmother, Azwihangwisi (50), at the Tswinga RDP section outside Thohoyandou.

But, in January, the school told Azwihangwisi that Israel would not be allowed back to the school because of his “underperformance”. Israel has never “passed any grade by his merit as he was always condoned”, according to a psychological report from Tshilidzini Hospital near Thohoyandou.

Israel has one lingering question: “When will I go to school?” Another question follows: “Will you pay for school transport for me?,” says the grandmother.

Israel still wakes up early in the morning and walks with his friends to the school’s transport pick-up point. He is still coming to terms with why he cannot go to school.

Although researchers acknowledge that there has been progress, they also point out how the basic education department has failed children with disabilities.

Two decades ago, South Africa adopted the Education White Paper 6: Special Needs Education — Building an Inclusive Education and Training System, a policy that recognises the constitutionally protected right of all children to quality education.

The policy provides direction on the steps needed to build an inclusive education system and “place an emphasis on supporting learners through full-service schools that will have a bias towards particular disabilities depending on need and support and introduce strategies and interventions that will assist educators to cope with a diversity of learning and teaching needs to ensure that transitory learning difficulties are ameliorated”.

Removing children with disabilities from mainstream schools contradicts the policy and research, which shows that inclusive education benefits learners, teachers and the education department.

A 2015 Human Rights Watch report states: “South Africa continues to expand its parallel special education system for people with disabilities and those deemed to have on-going learning barriers, preventing them from learning in an inclusive general school system.”

Special schools are not the solution

Israel’s remaining option was Fulufhelo Special School, for learners with intellectual disabilities, about eight kilometres from his home.

In February, Azwihangwisi filed an application at the special school and when she sought for the status of the application after six days, she was told the application had gone missing.

She then made a second application at the special school but was directed to the mainstream school for the principal to submit to the Vhembe district. She did as she was told.

“But when I inquired about the progress of the application, the deputy principal said one of the forms had been returned to the school by the district doctor because it had errors that needed to be rectified. I am still waiting,” she said.

Tswinga Primary School principal, Ms Tshamaano, declined to comment when asked about Israel’s second application which is currently stuck at the school, because she is not allowed to speak to the media.

Moko Ramaano, the principal for Fulufhelo Special School, said the school had never lost any forms, adding that the process to admit a child had become stringent, because it is now controlled by the Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support (SIAS) policy, a product of the Education White Paper No 6, which advocates for inclusive education.

A Human Rights Watch report states: “Research shows that social workers and education officials refer children to special schools, sometimes after a short stay in a mainstream school, but in many cases after a long and tedious process of referrals and assessments. Such referrals often prevent children’s entry into inclusive, mainstream education. This limits their access to a complete cycle of basic education, to which they are entitled by law. Many children are in special schools that segregate them and do not support their holistic development or cognitive skills.”

Ramaano said there are a couple of processes that still need to take place before Israel can be admitted to Fulufhelo Special School.

“So, we don’t just rush to admit a child. We admit a child by the directive and recommendation from the district. They should have agreed that indeed the child will not benefit from the mainstream, only a special school is [likely to be] the only place they will benefit at,” Ramaano says.

The deputy principal, Tshifhiwa Tshikosi, who is also the coordinator of the SIAS policy, said Israel’s second application forms were stuck at the mainstream school after they were returned by the district doctor, who had since retired.

Equal Education Law Centre

Robyn Beere, the deputy director at the Equal Education Law Centre, said the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation’s policy guidelines define inclusive education as a process that involves the transformation of schools and other centres of learning to cater for all children, including those with disabilities.

“A teacher in an inclusive school would be able to differentiate the way she teaches, the curriculum and assessment so that all learners are able to achieve and reach their full potential. Learning and teaching materials would cater to a range of abilities and the classroom environment would be welcoming, accommodating of difference and conducive for learning for all,” said Beere.

Asked whether Israel’s mainstream school acted lawfully by removing him without first having secured a space at the special school, Beere said: “At no point should the child have been removed from school and it should not have been the parent’s responsibility to try and find placement at a special school.”

Class interventions to support Israel should have been put in place and, where reasonable, accommodations beyond those “the teacher is able to implement — for example, assistive devices, concessions for assessment – the learner should have been referred to the school-based support team and an individual support plan put in place with the involvement of the parent”.

She said that if the school needed additional support, it should have contacted the district-based support team.

“The learner should have been accommodated at the school as far as possible, irrespective of whether or not he was able to function at grade level. If all involved considered placement at a special school would have as a last resort been in the best interests of the learner, the district office should have secured placement at a special school and the learner should then have been transferred from the mainstream school to the special school.”

Mike Maringa, the spokesperson for the Limpopo education department, had not responded by the time of publication.

Merriam Mabunda (54), of Tshitomboni village outside Thohoyandou, said it was an uphill battle to get her 16-year-old non-vocal son, Mashudu, into Fulufhelo Special School. He waited for four years and only managed to be enrolled at the age of 10 in 2016.The doctor had said that “he is not the type of a person to go to school” but did not give a reason.

Before he was enrolled Mabunda was asked if he could look after himself in the bathroom. And they asked about Mashudu’s interests. “He enjoys farming,” she answered. “That’s when they said they will admit him and teach him work that involves hands.”

Mashudu has since established a pigsty at the back of the house. She said he has made her a proud mother. “I hope this business will help him to realise his dream and become a commercial farmer.”

A system littered with remnants of apartheid

Critical disability studies researchers argue that the gaps in access to education for children with disabilities must be understood in the context of South Africa’s history. The apartheid education policies left former bantustans and townships disproportionally under-resourced, if at all. According to the book Disability and Change, edited by Brian Watermeyer, Leslie Swartz, Theresa Lorenzo, Marguerita Schneider and Mark Priestley, special schools and training of educators were only available for white people.

“For the majority of black people, their lives were about struggling on a daily basis to cope with the poverty, deprivation and violence of the apartheid system struggle compounded by their disability.”

These inequalities are glaring in provinces such as Limpopo. In 2020, the South African Human Rights Commission in the province released a report that demanded an urgent intervention into the dilapidated state of the schools for learners with special needs.

The commission also found that most of the 35 schools for children with special needs lacked learning materials, infrastructure and staff.

Limpopo-based activist Ramphele Mawelewele said: “Infrastructure in South Africa is a huge problem for people with disabilities. If the government prioritised accessible infrastructure for everyone, it would have halved most of the challenges differently-abled people face.”

Mawelewele works with various NGOs in the province, advocating for inclusive education for people living with disabilities. She became paraplegic in a car accident in November 2007, shortly after writing her matric.

She wants the government to make it mandatory for all schools to cater for people with disabilities.

This story was published with the support of Media Monitoring Africa and the United Nations Children’s Fund as part of the journalism lsu Elihle Awards initiative.