Art of liberation: Keorapetse Kgositsile in 2009. He was a pre-eminent cultural figure in the struggle, and was not afraid to critique the ANC’s ‘backwardness’ when it came to culture. His bridging of politics and art was one of his many talents. (Oupa Nkosi)

Keorapetse Kgositsile’s first country of residence after leaving the United States was Tanzania, where he was appointed at the University of Dar es Salaam. This was most opportune for him in his undying commitment to the national liberation movement and its ally, the South African Communist Party.

Here his proximity to Morogoro, where President Julius Nyerere apportioned land for the ANC to set up camp, 170km outside of Dar es Salaam, fulfilled a deep yearning held over the 10 plus years in exile in the US. The ANC set up the Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College to receive and educate the influx of post-1976 youth fleeing the genocidal white oligarchy after the Soweto Uprising.

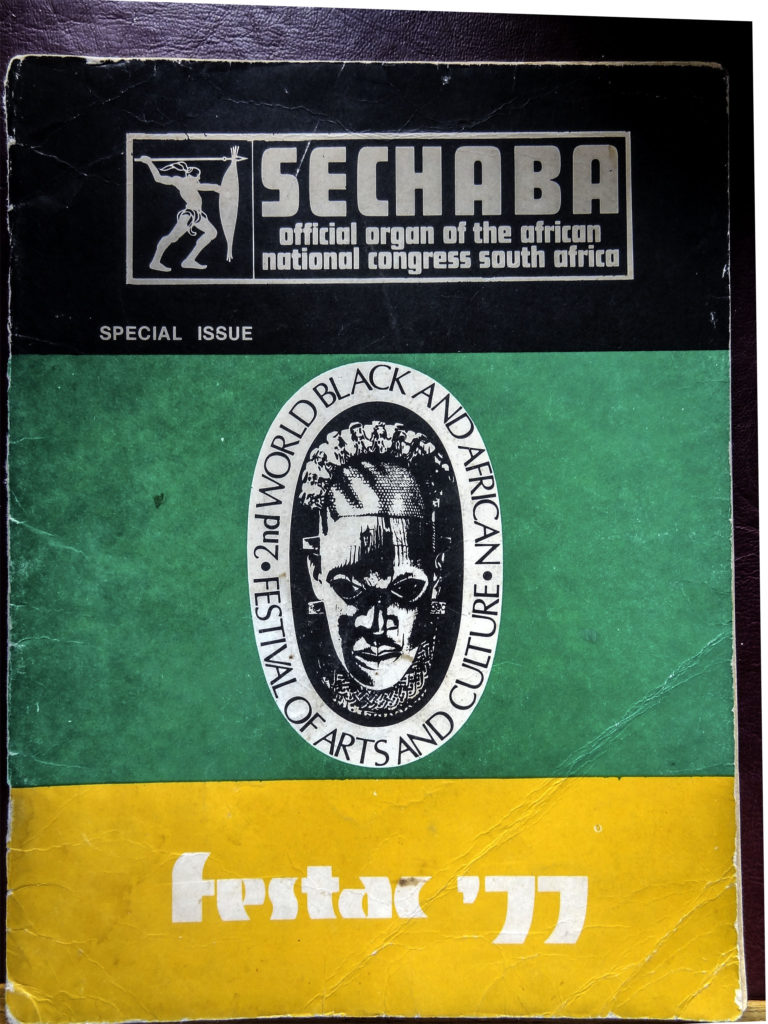

When the Nigerian government extended an invitation to the leadership of the external mission to participate in the monumental Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (Festac) hosted in Lagos in 1977, the ANC appointed Kgositsile to lead its cultural delegation.

This contingent included, in the majority, some of the youth freshly out of South Africa, still reeling from the effects of their deadly encounter with apartheid state machinery, while also navigating their newly-assigned exile status. In Nigeria, the students staged re-enactments of their confrontation with the white South Africa’s security police on the stages of Lagos, disarming even the local national army who were in attendance, who reportedly wept unreservedly.

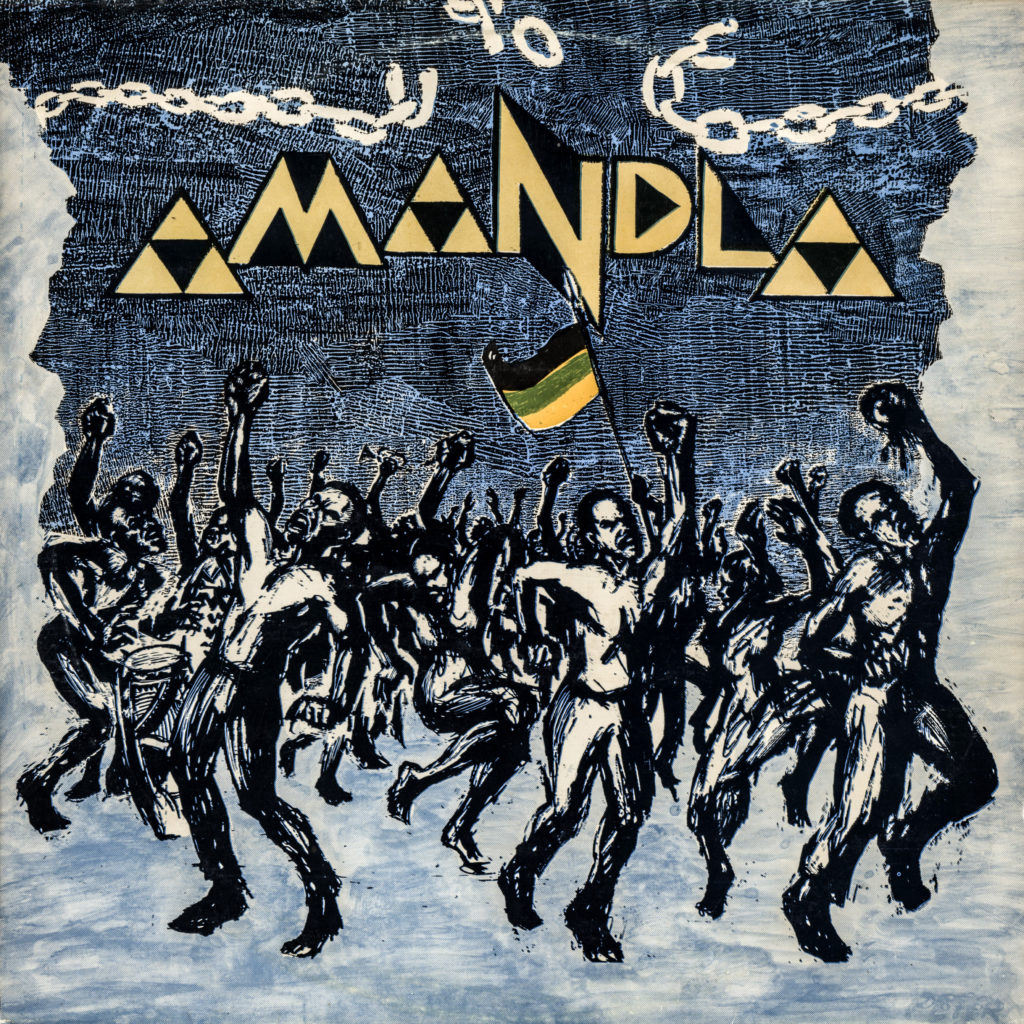

The “South African Question” was concretised in the pan-African imagination. In what became a decisive moment for the liberation movement’s relationship with culture as a weapon of resistance, the ANC’s Mayibuye Cultural Ensemble, later the Amandla Cultural Ensemble, became a core component of ANC’s external mission, spearheaded by Kgositsile.

Amandla Cultural Group – First Tour Live, 1983

Amandla Cultural Group – First Tour Live, 1983

After Festac, the ANC began establishing regional cultural committees globally, including, notably, in the Scandinavian countries, where another cultural stalwart Lindiwe Mabuza was the party’s ambassador, soliciting financial support through anti-apartheid solidarity movements in countries such as Sweden, Norway, and Finland.

The Amandla Cultural Ensemble would find wide reception and hospitality in these countries throughout the 1980s. Her efforts also led to the publication of an anthology of ANC women’s poetry in 1981, Malibongwe, a crucial surviving document of women’s experiences in the camps across Southern Africa.

In 1980 the ANC adopted tactical principles aimed at developing insurrectionary potential in the townships of South Africa from neighbouring Botswana. This was an all-out people’s war mandated by the ANC’s declaration of 1979 as the Year of the Spear. There, in Gaborone, a troupe of artists with ANC affiliations had formed an art collective called Medu Art Ensemble — a pivotal historical organisation that comprised visual artists, musicians, literary and dramatic practitioners. Among the members were ANC-trained members Wally Serote, Thami Mnyele and Mandla Langa, as well as Judy Seidman, Bachana Mokwena, and Dennis Mpale, who all tasked themselves with providing “propaganda” to send to South African townships to detonate a popular revolt.

As links between the ANC in Botswana and progressive organisations at home continued to strengthen, the ANC sent to Medu Kgositsile and his then-wife singer, poet, and comrade Baleka Kgositsile (née Mbete). They arrived there in 1982, and Kgositsile also took up a post at the University of Botswana.

That year the definitive Culture and Resistance Conference, organised by Medu, was held from July 5 to 9 at the University of Botswana, under the impetus of examining and proposing suggestions for the role of art in the pursuit of a future democratic South Africa.

Sechaba Festac special issue cover.

Sechaba Festac special issue cover. The conference was unabashedly pro-ANC in agenda and orientation. Kgositsile was keynote speaker, and his passionately partisan speech set the politicised tone for the rest of the festival, seen in the adaptation of the term “cultural worker”, which he proposed to mitigate the elitist and western associations of the term “artist”. He saw a cultural worker as not being any different to a nurse, teacher, or football coach, all there to meet the needs of the struggle. He used his keynote address as a vehicle for pushing the ANC to take culture seriously.

Kgositsile proclaimed: “The past few years have seen attempts by the artist, both at home and in exile, to organise themselves with the struggle and fashioning ways of making their talents functional in their communities and to the struggling masses of the people as a whole. Mayibuye, Amandla! are examples of such cultural collectives”.

He further asserted that there was “no such creature as a revolutionary soloist” in a struggle for national liberation — a dream is not a dream, if not the dream of the community; “all else is criminal”. “Cultural worker” became the phrase of the moment and moulded the politicised propagandist work that came out of Medu, moving across the border through the underground into South African townships.

Kgositsile’s bridging of politics and art, which he himself modelled, also bridged the young cultural worker in the ANC camps with the international solidarity campaign, finding support in the more culturally progressive governments of Cuba, the Soviet Union, Scandinavia, Britain, and other African countries that had been anti-apartheid allies, throughout the 1980s.

In this way, Kgositsile elevated the position of the “cultural worker” to that of any other worker in the struggle, perhaps even more crucial in garnering international solidarity through art’s ability to speak to more than just the head, but also the heart. I note with great enthusiasm how the term is beginning to gain traction today, which attests to the power of culture as a weapon to define and assert blackness in its own terms under apartheid, and also points to our cultural archive as continuously generative to serve those needs today. It also, sadly puts a spotlight on the ANC’s continued disregard for artists.

Out of these developments, the role of culture in the struggle for national liberation became a mainstream agenda in the ANC’s external mission. By this time, Kgositsile was also notoriously outspoken about the “backwardness” of the ANC when it came to culture — “within the movement there is an annoying, criminal backwardness about culture, generally, and its role in society at any given time”, he lambasted in an article published in the ANC’s magazine. He laments that “it took the ANC until 1982, a period of seventy years, to establish the department of arts and culture; and that was after the unarguable success of the historic Culture and Resistance festival earlier that year”.

That festival/conference was a watershed moment which led to the establishment of the department of arts and culture in exile, and the launching pad of the in-house cultural journal, Rixaka. Kgositsile was appointed deputy minister of that newly found department, headed by Barbara Masekela.

This new department was represented at the Culture in Another South Africa conference in Amsterdam in 1987, organised by the Dutch Anti-Apartheid Movement. Its proceedings are recorded in the documentary Before Dawn, and can be viewed on Vimeo. This conference symbolises many gatherings of this type in the 1980s, focusing on culturally boycotting apartheid and on divestment, putting pressure on the apartheid government from the outside, and leading to the state of emergency to be declared. It was cultural workers who concretised and animated the politics and policies of the external movement, spreading anti-apartheid fires globally, driven by the will and undying resolve of the masses on the inside.

In 2004 Kgositsile was appointed special adviser to then minister of arts and culture, Pallo Jordan, and in 2006 the title national poet laureate of South Africa was conferred to him by that minister, recognising his efforts in being uncompromising about his position on the arts, and his valour in critiquing the ANC’s short-sightedness on the subject.

Uhuru Phalafala (PhD) is a lecturer at Stellenbosch University. She is currently completing a monograph on Keorapetse Kgositsile titled Black Radical Traditions From the South: Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement. She heads a project that repatriates and republishes apartheid-era cultural production, which has recently republished an anthology of ANC women’s poetry from 1981 titled Malibongwe (uHlanga 2020). Her project Mine Mine Mine is a mythopoetic chronicle of her grandfather’s journey as a migrant worker in the gold mines of Johannesburg

To purchase a copy of the Festac ’77 book, please visit this website