Better together: Louis Moholo-Moholo and his wife Mpumie were a package. (Photo: Courtesy of family)

It is often said that a beautiful soul shines through a person’s eyes. That was certainly true of Nompumelelo Ebronah “Mpumie” Moholo. She had the kind of captivating natural beauty that attracted writers and musicians, who adorned their book covers and record sleeves with her face. Artists sought her out for the subject of their portraits.

But those were the externals. Mpumie’s soul also shone through her splendid character, mental strength and rich compassion. She was unfailingly honest, not only to others, but also to herself. Her patience was inexhaustible, and she never judged.

A few decades ago, I stayed at the home of Mpumie and Louis Moholo-Moholo in London. The warmth of their home attracted people from every walk of life, from artists to politicians and more.

Mpumie loved to cook and serve huge plates of food designed to satisfy even the most gluttonous. I can think of no better analogy for the grip of African culture on her outlook than that food, especially township delicacies like samp and mogodu, or tripe. Despite having dined in restaurants around the world, the best place for her was her own kitchen.

Mpumie was born in the Cape Town suburb of Retreat on 6 August 1947. Like other black South Africans, her family was then subjected to apartheid’s harsh regime of influx control and forced removals: uprooted to black townships away from the white suburbs. Mpumie’s mother — known to everybody as Sis’ Jean — married musician and intellectual Nation Mtwana and the family settled in Harlem Street, Langa, where Mpumie’s siblings were all born. Sis’ Jean died in 2003, but Mpumie inherited a lot from her, especially her commitment to Langa women’s struggles for the education of their children.

African musicians suffered under apartheid: forced to labour at day-jobs and able to exercise their creativity only after work, for pitifully small rewards. The life was exhausting. To persevere demanded huge sacrifice from families. It’s hard to estimate the commitment this involved, and the role of women in preserving and carrying the art form of jazz forward.

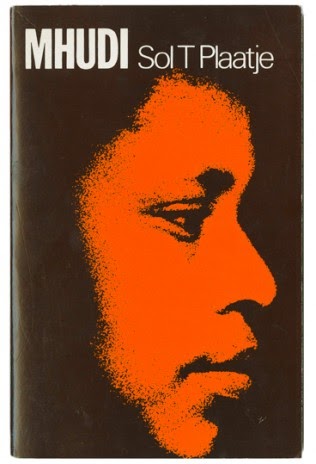

The 1978 republication of Sol Plaatje’s Mhudi (Heinemann Press) features an image Mpumie Moholo

The 1978 republication of Sol Plaatje’s Mhudi (Heinemann Press) features an image Mpumie Moholo

Apartheid’s oppression and exploitation of male jazz musicians was equally the exploitation of these indomitable women, who inspired their husbands, took care of their children and kept the home fires burning. Male artists earned so little, and so intermittently, that women were often also the main breadwinners. I’ve heard wives say: “He’s my man, even though sometimes he’s not treated like one.”

Mpumie studied nursing at McCord Nursing College. After graduating, she worked in several hospitals as a triple-qualified nurse: a coveted career for a black woman then.

Louis Moholo-Moholo had left South Africa in 1964 with the rest of the Blue Notes, to play at the Antibes Jazz Festival. He was already living in London, fighting his own battles against the cold climate and colder attitudes. In 1973, he returned to Langa to visit his mother. That’s when he met Mpumie.

I think it was love at first sight for both of them — followed by an appreciative second look. They married almost immediately and Mpumie left South Africa to be with Louis. She stayed and worked in England until both returned home in 2005.

There are highs and lows to being in a musician’s family. Some musicians compromise, deserting creative originality and plodding through routine gigs to pay the bills.

Moholo-Moholo never did that, and was respected in avant-garde jazz circles worldwide for his unique, free approach to the drums. That he held on to his vision sheds more light on the role of partners: they also provide intellectual encouragement. If we could hear even a fraction of what goes on in musicians’ homes behind closed doors, those soul-searching conversations might break our hearts. Only if a musician has a breakthrough does the situation change. Then, wives may get to travel the world with their husbands. But it’s always precarious.

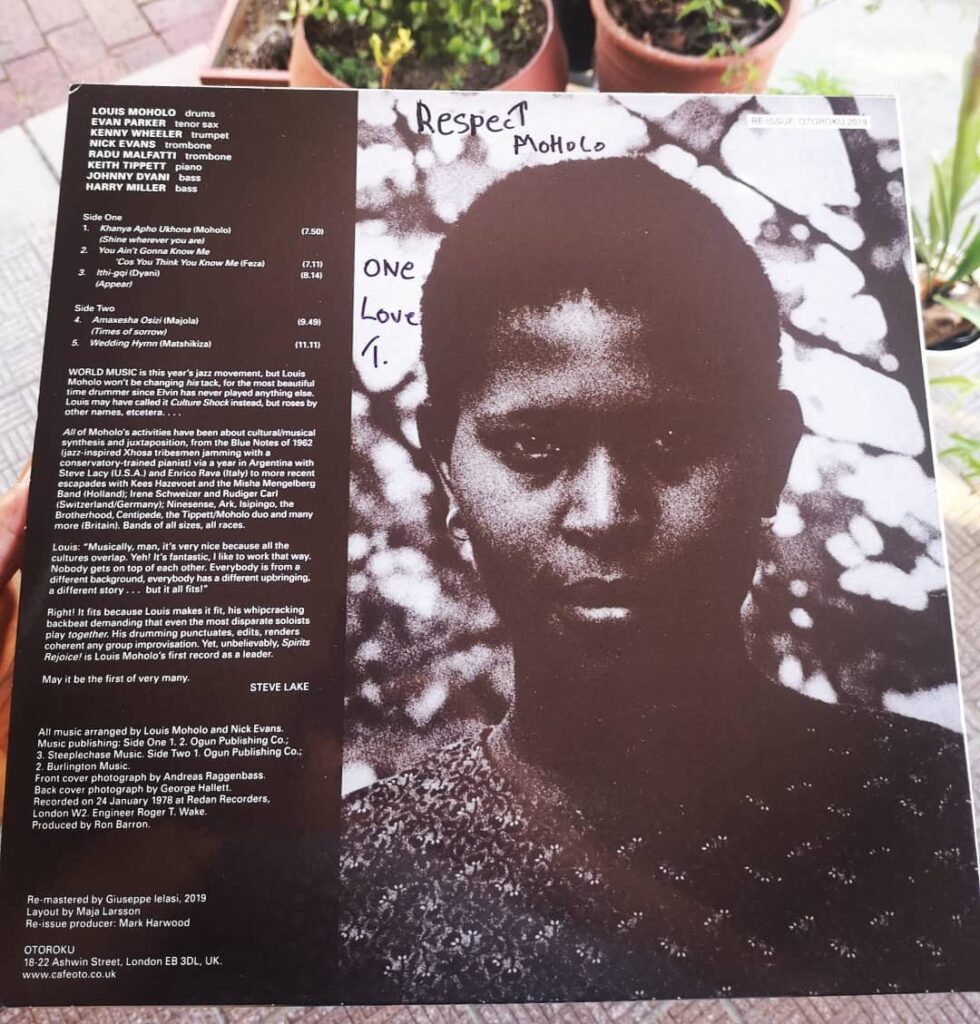

A picture of the back cover of the Louis Moholo Octet’s Spirit Rejoice! album, featuring an image of Mpumie Moholo. (Picture courtesy of Atiyyah Khan)

A picture of the back cover of the Louis Moholo Octet’s Spirit Rejoice! album, featuring an image of Mpumie Moholo. (Picture courtesy of Atiyyah Khan)

Every great musician has a dynamic partner by their side. And that was Mpumie: the engine of her husband’s success. Louis Moholo-Moholo’s drums were also an engine behind the revolutionary South African bands that transformed the European modern jazz scene.

And Mpumie was always there. She solicited and arranged gigs, oversaw recording contracts and performance dates, and compiled publicity, all the while nurturing the health and welfare of the family. She encouraged her husband to create even in their darkest moments.

It takes an extraordinary woman to make that kind of contribution to this art form. Louis Moholo-Moholo and Mpumie were a package; she merits the same attention as, say, Yoko Ono in the musical growth of John Lennon.

When they returned to South Africa, the travelling continued. Because Mpumie was so strong, we all missed the signs of exhaustion and fatigue. The signs that her health was weakening were ignored. And she wouldn’t slow down.

In September 2019, she helped to organise a duo set for Moholo-Moholo and Italian pianist Giovanni Guidi at the Guga S’thebe Cultural Centre. During that set he collapsed. Mpumie was at hand to help, and he was rushed to hospital.

Mpumie closed the book with a brilliant final chapter. She dedicated her life to freedom: not only the freedom in Louis’s music, but freedom from hate, self-pity, self-interest and the kind of pride that might make another person feel they were better than their neighbour. Those freedoms validate Mpumie not only as the daughter of her family, but as a national treasure: truly a first lady of South African jazz.

Madoda Nethi is Mpumie’s brother-in-law and a former chairman of the Western Cape Jazz Appreciation Society