Sports, arts and culture minister Nathi Mthethwa handing over Radio Freedom equipment. (Photos: Jairus Mmutle/GCIS)

The recent calls for the removal of Sports, Arts and Culture Minister Nathi Mthethwa by members of the arts, culture and heritage community seem to miss the bigger problem, which political economy scholar and ANC member Oscar van Heerden posits is, “The ANC is confused (ideologically and strategically), therefore the government is confused, and therefore the state is confused.”

Although Van Heerden’s remark was made in light of the evidence relating to the State Security Agency at the Zondo inquiry into state capture, I am of the view that the confusion he identifies pervades all the departments of government, not least the department of sports, arts and culture.

It is no secret that South Africa is facing an acute leadership crisis. This is why the calls for Mthethwa’s resignation are not misplaced. He has presided over a department that has come to be known more for its professional mourning services rather than “providing leadership to the arts, culture and heritage sector to accelerate its transformation” (as per its official mandate set out in the various drafts of the revised white paper on arts, culture and heritage, which still hasn’t been finalised).

As important as fixing the problem of ineffective leadership is, we cannot lose sight of the ideological crisis — especially as it relates to the role of the arts and culture to postcolonial nation formation — the ANC has been in since at least the late 1960s. This crisis, according to literary scholar Ntongela Masilela, has to do with the ANC’s “enforced separation of politics and culture”.

Although the contemporary ANC can be rightfully characterised as having “no intellectual ideas left” (as Van Heerden does), the dominance of orthodox Marxist-Leninism in the ANC leadership circles for most of the second half of the 20th century led to the development of a bureaucratic view of the arts and culture.

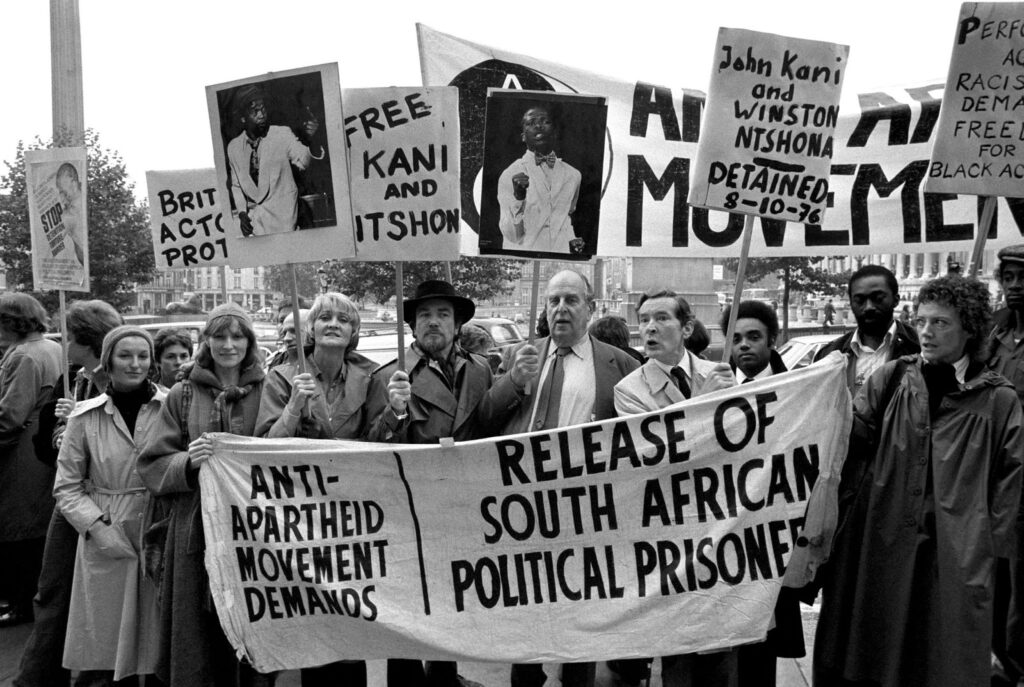

Anti-apartheid actors protest outside the South African embassy in London. (PA Images/Getty Images)

Anti-apartheid actors protest outside the South African embassy in London. (PA Images/Getty Images)

In 1992, the poet Keorapetse Kgositsile cautioned against this bureaucratisation when he criticised the ANC’s “criminal backwardness about culture, generally, and its role in society at any given time”. Even when it established its department of art and culture in 1982 (to house the activities of Medu Art Ensemble and Amandla Cultural Ensemble), Masilela accused it of having “created a performance space for the arts rather than a place for cultural production”.

Perhaps the most glaring example of how lowly the arts and culture have come to be regarded by the governing party is how this site of struggle is now lumped together with sports and recreation. This relegation suggests that, contrary to the revised white paper’s admission that “decolonisation of the sector leaves much to be desired”, the current administration views the arts as mere entertainment for “the masses” — meaning that the official conception of the arts and culture is a non-ideological one, or so it seems.

The bureaucratisation of the arts and culture is largely to blame for the dramatic shift from “the emergence of community-based cultural organisations openly aligned to the struggle against apartheid” to the post-1994 function of the arts and culture as an instrument of rainbow nation social cohesion. As argued by the #RhodesMustFall movement of the recent past, the rainbow nation-building project is a farcical maintenance of whiteness in blackface. This is despite its pretences as a pragmatic programme of action.

The daily occurrence of so-called service-delivery protests over the past 15 years represents the most sustained levels of much-needed contestation around the very idea of “post-apartheid South Africa”. So, the government’s propaganda of “social cohesion and nation-building” through the arts can only be read as an attempt at “manufacturing consent” (to twist the title of Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky’s influential book, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media).

What is to be done by artists and cultural practitioners in this state of confusion? One answer would be that artists must simply “go to work” and “reflect the times”. With much love and respect to Toni Morrison and Nina Simone, this is easier said than done. My view is that artists have to refuse the reduction of their work to “entertainment”. Where entertainment lulls and desensitises the audience, I am arguing that contemporary artists have to think seriously about aesthetic practices that would heighten our senses for the purposes of what sculptor and poet, Pitika Ntuli puts as “building our resistance” to injustice.

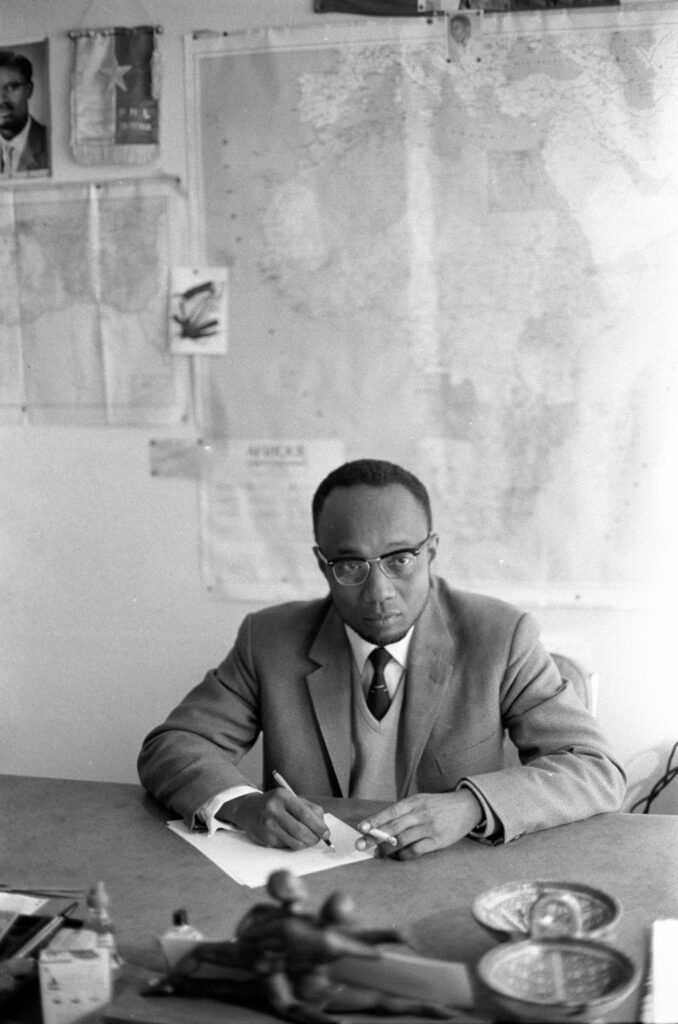

Guinea-Bissau anti-colonial leader Amílcar Cabral. (Ben Martin/Getty Images)

Guinea-Bissau anti-colonial leader Amílcar Cabral. (Ben Martin/Getty Images)

Contrary to those who say that we should not weaponise the arts and culture, the words of Guinea-Bissau anti-colonial leader, Amilcar Cabral, that “you measure a people’s potential for liberation based on how different their culture is from their oppressors”, should haunt all of us. To what extent can we say that contemporary South African cultural life is different from that which prevailed in colonial-apartheid times? Is there even such a thing as a “post-apartheid national culture”?

These questions implicate the process of nation formation that has been led by the ANC. I emphasise this idea of process precisely because a nation is not a given: it is formed through social and political processes. Any claim to the contrary must be viewed as an attempt to bamboozle the people — what Cabral would describe as an “easy victory”. The ANC’s failure to fully decolonise this country necessitates a continuation of the struggle in and for representation; a struggle that should be waged on the ground and in our minds.

The role of artists in such a struggle would be to help us to imagine a new country, not to hustle whoever is in charge of the ministry of arts. Yes, artists (particularly those who are black) have been reduced to mere beggars for the next grant or residency. But which poor black person hasn’t been reduced to either a hustler or a beggar? The precarious situation facing artists won’t improve if the general structural conditions don’t change. It seems to me that many more artists would have to start seeing their position in relation to the people at large. Work awaits all of us.