Elusive: The documentary Chasing Trane fails to catch the full John Coltrane.

Not all professors or the public are sold on John yet. I have heard quite reputable critics put Coltrane down for reasons that are sometimes extra-musical, sometimes extra-rational. But, to my mind, the greatest disparagement of John Coltrane must come from those who cannot hear what he is doing. From people, well meaning and/or intelligent as they might be, who simply do not hear the music.

Another reason why people might not be able to hear John Coltrane might be the simple fact that he is such a singularly unclassifiable figure; almost an alien power, in the presence of two distinct and almost antagonistic camps. John’s way is somewhere between the so-called mainstream and those young musicians I have called the avant-garde.

John Coltrane is in neither camp, though he is certainly a huge force in each. Most of the avant-garde reedmen are beholden to John and a great many of the new mainstreamers think they are John Coltrane. Trane’s influence moves in both directions … sometimes detrimentally (Benny Golson, Cliff Jordan, et cetera); sometimes to great effect (Wayne Shorter, Archie Shepp).

Coltrane’s move from being just another “hip” tenor saxophonist to the position of chief innovator has to be traced from the beginning of his recorded efforts and all those changes, resolutions, and transmutations in Coltrane’s approach to his instrument documented to get a more complete picture of just what has happened between that chorus with Miles and My Favorite Things.

And even the most confirmed Coltrane debunkers must agree that a whole lot has gone on during that time … like it or not. But I think the trilogy — starting with the first Atlantic album, Giant Steps, proceeding through Coltrane Jazz, and coming finally to My Favorite Things — shows Trane’s development, from sideman to innovator, in microcosm.

Before the trilogy, and after the Columbia album with Miles Davis, Milestones (the solo on Straight No Chaser), it became evident that Coltrane was moving into fresher areas of expression. That solo, even though in some senses it was the most “lopsided”, ill-thought-out solo Coltrane has produced on records, still contained more fresh thinking about how one is supposed to play the tenor saxophone post-Coleman Hawkins/Lester Young than anyone else around had shown.

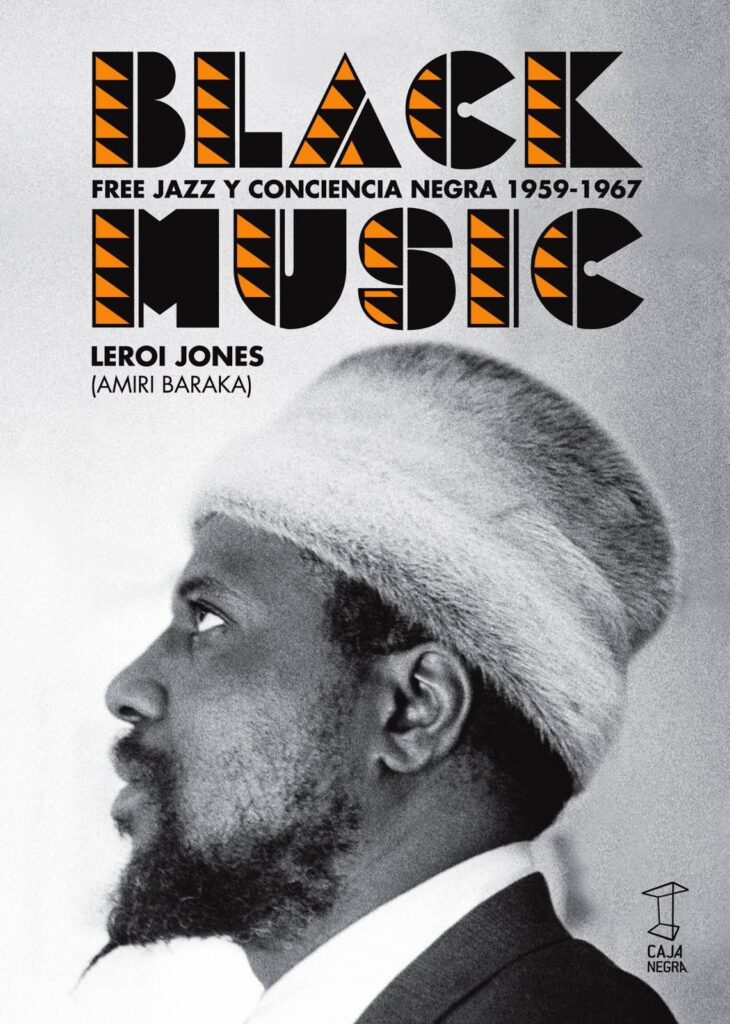

Amiri Baraka’s Black Music, a collection of reviews, essays and reflections

Amiri Baraka’s Black Music, a collection of reviews, essays and reflections

The masses of 16th notes, the new concept of using whole groups or clusters of rapidly fired notes as a chordal insistence rather than a strict melodic progression. They, the notes, came so fast and with so many overtones and undertones, that they had the effect of a piano player striking chords rapidly but somehow articulating separately each note in the chord and its vibrating subtones.

It is the prison of the changes or the recurring chords that sent Ornette Coleman and so many others recently over the hump … so they play as if they were paying no attention to the chords at all (which, of course, is not true).

Coltrane’s reaction to the constant pounding chords and flat static, if elegant, rhythm section, was to try to play almost every note of the chord separately, as well as the related or vibrating tones. The result is what someone termed “Sheets of Sound” or, more derogatorily, “just scales”.

After Straight No Chaser, Trane began to find out exactly what he was doing. But a great many times the chord jungle just caused him to run around and around, hoping somehow to get into that thing he’d found and was trying to work out.

I heard him several times during that period, just after he stopped playing with Monk. One night he played the head of Confirmation over and over again, about 20 times, and that was his solo. It was as if he wanted to take that melody apart and play out each of its chords as a separate improvisational challenge.

And although it was a marvellous thing to hear and see, it was also more than a little frightening; like watching a grown man learning how to speak … and I think that’s just what was happening.

This edited extract of A Jazz Great: John Coltrane (1963) is taken from Amiri Baraka’s Black Music (Akashic Books).