Because Katrina Esau is one of very few remaining speakers of the N|uu language, she decided to publish a children’s story in her mother tongue, saying it was a ‘matter of the heart’ for her. Photo: James Oatway/Gallo Images/Sunday Times

At a 2017 lecture titled Decolonise the Mind, Secure The Base delivered at Wits University’s Great Hall, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, that lucid man of letters, elaborated on his lifelong quest to preserve and elevate indigenous African languages. “If you know all the languages of the world and you don’t know your mother tongue or the language of your culture, that is enslavement. But if you know your mother tongue or the language of your culture, and add all the other languages of the world to it, that is empowerment,” the writer and scholar explained.

I recall this and other seminal moments in the struggle to preserve and promote our relegated languages in a discussion with Puku Books founder Elinor Sisulu, in the aftermath of the launch of Katrina Esau’s groundbreaking children’s book in the near-extinct San language of N|uu. Sisulu is excited and encouraged by the publication of the book, and Puku Books’ (which focuses on the promotion of children’s literature in our indigenous languages) involvement in bringing the book to life.

“Children’s books written in our mother tongues are at the heart of the decolonisation project,” Sisulu says.

We both know that this is a statement of what ought to be, rather than what is. By error or design, children’s literature in indigenous languages has thus far existed only in the margins of decolonisation campaigns that have been gathering speed in recent times.

The Puku Books founder is absolutely correct, of course, in her assessment of the significant place children’s literature ought to have in our national life and consciousness. She is also very clear about the role that translation can play in kickstarting a reawakened sense of the importance of our languages, preserved in literature.

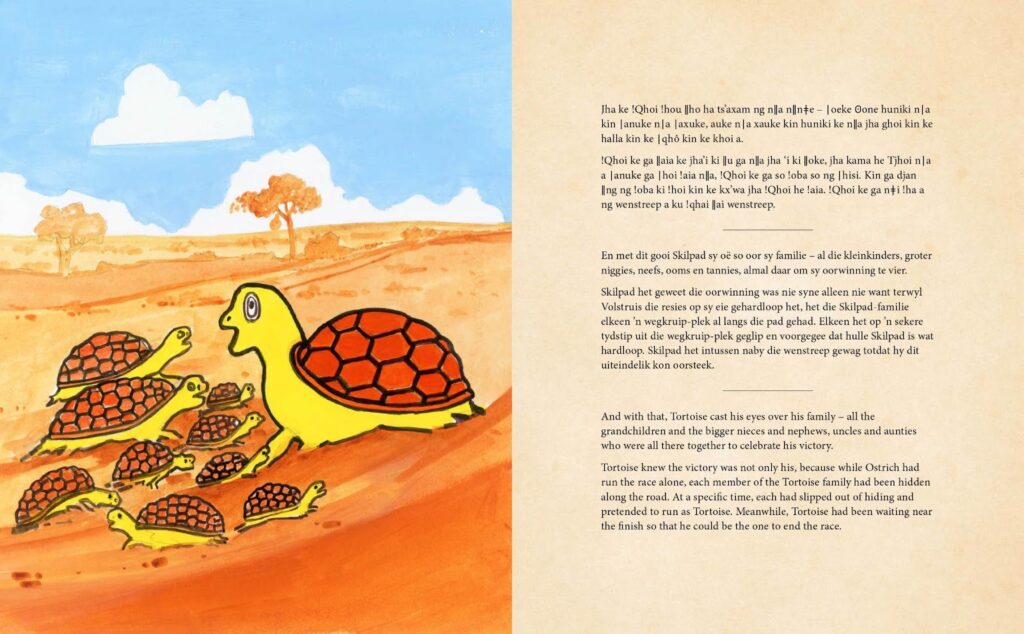

Katrina Esau’s book is a trilingual endeavour, featuring English and Afrikaans translations alongside the narration in N|uu, which is the last surviving of the Tuu cluster of San languages.

There are only a handful of people fluent in N|uu left alive, Sisulu explains, including the 87-year-old author Esau and her granddaughter, Claudia du Plessis. It only made sense to go the route of translation, in order to achieve a broader interest in and wider readership for the book.

“Going forward,” Sisulu says, “we envision a future where this translation can happen between indigenous languages, so that a children’s book in Tshivenda could be translated into Setswana and Xitsonga and isiXhosa, and so on. We see that kind of cross-pollination happening even at the level of university departments, with literature as well as with academic texts. But the beginning, the foundation, has got to be in our children’s literature.”

‘Children’s books written in our mother tongues are at the heart of decolonisation,’ says publisher Elinor Sisulu

‘Children’s books written in our mother tongues are at the heart of decolonisation,’ says publisher Elinor Sisulu

Having read Ouma Katrina’s book, I am willing to attest to Sisulu’s assertion that there is a great deal of care and complexity involved in the practice of writing for children. It is without doubt only deceptively simple.

The publication of !Qhoi n|a Tjhoi/The Ostrich and the Tortoise is the culmination of an unwavering commitment on Esau’s part to save the endangered N|uu language. She has previously converted her tiny home on the outskirts of Upington into a school where she teaches the language to children.

The small border town of Upington is in the province of the Northern Cape, whose provincial motto, Sa IIa !aisi uisi (We go to a better place) is in N|uu. In an age where virtue-signalling has become the norm rather than the exception, the conversation rightly shifts to the dangers of paying only lip service to the sacred work of preserving and promoting our indigenous languages, relegated as they are to the margins of our mainstream cultural endeavours.

Sisulu recalls the renowned Gcina Mhlophe, storyteller supreme and celebrated across this land, decrying the fact that this society only acknowledges her for appearances’ sake, without the material support that would make a tangible impact on her work and art.

“What does it help me, to be celebrated and fêted, and yet continue to struggle in my daily life, with limited means at my disposal?” the master storyteller once famously asked.

Esau, too, has been a recipient of accolades whose actions do not match up to their words. Awarded the National Order of the Baobab in Silver in 2014, it would seem that her language advocacy work has not received the kind of support such a move seemed to portend. Her fledgling academy, named !Aqe IIX’oqe (Gaze at the stars), established at a time when the language of N|uu (which she describes as “the language of my soul”) was thought to be extinct, has survived on little to no material assistance since then.

More recently, Esau has featured in the department of sport, arts and culture’s Living Human Treasures series of booklets, sharing this honour with the luminary artist Esther Mahlangu, musician Madosini, and sculptor Noria Mabasa.

Sisulu points out that Puku Books, enabled in part by a government PESP grant to the organisation, has been able to add material reward to its support of Esau’s efforts, culminating in the publication of her book, and is anxious to do more.

The Ostrich and the Tortoise typifies how a great deal of care and complexity is involved in the practice of writing for children.

The Ostrich and the Tortoise typifies how a great deal of care and complexity is involved in the practice of writing for children.

Explaining her reasons for doing what she does despite limited means, Esau speaks for all of our marginalised indigenous languages when she says, “The aim of the work is that we want to hear the language. We also want to see it in books. We want to keep it visible. We are doing this because it is a matter of the heart for us.”

Despite her age, Ouma Katrina Esau still has exciting plans for the work involved in preserving her beloved N|uu. She has previously made known her intention to produce audio and video materials that would enable all who are interested in learning the language to do so remotely. Puku Books has committed to walking this challenging journey with her and to making sure that the dream remains alive even when this heroine is no more. The organisation hopes to continue collaborating with other partners in this regard, some of whom have given invaluable support to publishing her book. These include the Africa Publishing Innovation Fund, the Embassy of Switzerland, the National Arts Council, the National Film and Video Foundation and the National Library of South Africa.

Bodour Al Qasimi, the President of the International Publishers Association (IPA), stated in a special message sent through to the launch of Ouma Katrina’s book that it is “thrilled to see Puku Books’ goal to contribute to the survival of the N|uu language come to fruition with the launch of The Ostrich and the Tortoise in the N|uu language. The preservation and promotion of indigenous languages is a pillar of the IPA Africa Publishing Innovation Fund, and Puku’s work in this area is absolutely essential to this undertaking in South Africa.”

The work of writing children’s literature in our mother tongues is deeply important in the context of our diverse nation. That is where we begin to water the seeds of our long-overdue projects of decolonisation.

The book is available through puku.co.za