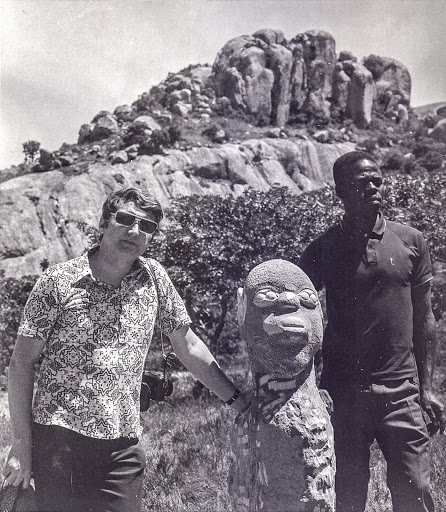

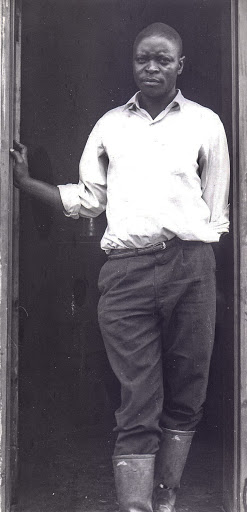

Joseph Ndandarika, who was once described as one of the three greatest living stone sculptors. (Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe)

In the act of remembering the Zimbabwean sculptor Lazarus Takawira, who died of Covid-related complications on 12 January, it is impossible not to talk about Frank McEwen, the founding director of Rhodes National Gallery (now the National Gallery of Zimbabwe) and the prime mover of the International Conference for African Culture of 1962. It was McEwen, the British curator, museum administrator and the man credited with promoting Shona stone art in the West, to whom Takawira sold his first sculpture, when the artist was barely a teenager.

Takawira was born in Nyanga, in the east of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), in 1952, to a father who was a Rhodesian policeman and a mother who was a sculptor. Female sculptors were a rare phenomenon then, and are not common even now. This background set the young Takawira on the path of first being a cop, then a sculptor, just like his mother and elder brothers, John and Bernard.

In 2016, when I went to interview Takawira at his farm outside Ruwa, on the eastern outskirts of Harare, he received me regally and warmly while seated in the sunny garden of the huge house he shared with his wife. In the two or so hours I was in his presence, he remained seated, his long legs stretched out in front of him.

At the time, as Takawira told me later in the course of our talk, he was struggling with gout. Because of his huge frame, he was popularly known as “Giant” (he wore a size 13 shoe), yet he must be the gentlest of all Zimbabwean sculptors, one of the few who were sensitive to women and the figure of the female.

Not only did he work with his wife, who helped him with the polishing and finishing of stones, but his artistic practice and its tropes can be traced directly to his mother and women. In the interview, unusual for a man of his generation, Takawira affectionately referred to his wife as “this girl”, and spoke about the various holidays in Zimbabwe and abroad they regularly took after the sale of his stones.

In the way Takawira spoke of his sculptural practice — in the diffident tones of courtship under moonlit pastoral landscapes — it’s clear he was looking for his own secret language of stone. In a Shona showing the eastern Manyika accent spoken in Nyanga, the scenic highlands where he grew up, he told me, “You don’t just randomly approach a girl and say ‘Ndeipi?’ No, no, no.” The word “ndeipi” can be translated as “Hey, what’s up?” Between peers and friends, it is a sign of familiarity, but said to a stranger, it is brusque.

“You have to find the best means to make your approach. Likewise, stones also need a nice approach. A sculptor shouldn’t just cut into a stone randomly,” he said, “because every single rock you see, even the stone you see lying on the road, is already a sculpture. What needs to be done is shaving the dirt away and it will end up a sculpture. So what I want to do is to teach these youngsters how to approach a stone because a stone, on its own, can speak.”

“You look for a stone, and find a story to etch onto the stone. Sometimes, to get the story, you have to force a stone; other times there is no need to force it. Sometimes, it even tells you, ‘This is how I want this story told.’ After you are done working on a stone, it will begin talking to you, whispering at you. Wamubudisa zvakanaka anotanga kutaura newe.”

For a man who uses the diction of romance to speak about his sculptures, it’s not a surprise that most of Takawira’s sculptures are of women. In rural landscapes of the mid-20th century, gender roles were segregated and mothers were usually a spectral — not pragmatic — influence on their sons (most men of that era cannot cook).

Strangely for a line of work dominated by men, his brothers were not his major influence; it was his mother, a largely forgotten figure, whom he endlessly referenced in his works and who taught him how to sculpt. Takawira’s brothers, John and Bernard, came to be celebrated artists and key figures in the artistic school more commonly and, misleadingly, known as Shona sculpture — misleading because many of the artists were not Shona-speaking, but of Malawian and Mozambican origins; and also because, before the late 19th century when the so-called Shona stone art came into being, no one really called themselves Shona.

Takawira’s mother started off in Nyanga, working with pottery, and then from clay moved to carving wood. It was by chance that a man called Joram Mariga, universally acknowledged as the 20th century (re)founder of the ancient artform of stone sculpting, also considered Nyanga his base. (The other key node of the stone sculpture movement is Tengenenge, in Guruve, in northern Zimbabwe, founded by the South African-born tobacco farmer Tom Blomefield).

Mariga, whose day job was in the civil service as an agricultural demonstrator, mudhumeni in the local parlance, had started off carving wood, after seeing his brother and father do it. It was Mariga who encouraged Takawira’s mother to start carving stone and, following his advice, she began working on stones.

When the young Takawira came back from school, she would often ask him to finish her stones. “Sometimes I didn’t like the task because it was dirty work, but my mother would beat me and insist that I finish the stone,” he said. Mrs Takawira wasn’t the only one Mariga inspired; others include Crispen Chakanyuka, John and Bernard Takawira, Kingsley Sambo and Moses Sambo.

The young Takawira’s fate would change, one day, after encountering McEwen, who used to visit the Nyanga workshop every month to buy artworks and check on the artists. On seeing a sculpture of a bird with its head turned backwards, he asked who had made it and, when told it was the young Takawira, he offered to buy the avian stone. Initially reluctant to sell the stone, Takawira did so only at his mother’s insistence and from the sale got £5 — a lot of money then — which the pre-teen artist used to buy a suit and shoes.

II

Frank McEwen, who was born in Mexico to British parents, arrived in Salisbury (now Harare) in 1957 to take up the director’s position at the still half-finished Rhodes National Gallery edifice — a squat, stylish Art Deco building. The structure, at the top of King’s Crescent (now Julius Nyerere Avenue), was designed by a local architect firm, Montgomerie and Oldfields, students of Le Corbusier, the Swiss-French pioneer of architectural modernism.

On his way to take up the position of director, McEwen had embarked on a triangular, months-long journey across the Atlantic, which began in France and took him to Rio de Janeiro, ending up in Cape Town. “This voyage sounds useless to the arts: from my point of view, it was not,” McEwen later wrote. “Isolated in open oceans for many months, sailing from ardent centres of civilisation towards one of their furthermost developments, I was able to ‘decant’ meditations on the future and clarify them more and more.”

Since his decision to study at the Sorbonne Institut d’Art et D’Archéologie, the École du Louvre, and the Académie Julian, after elementary education in London, France had been his base. After studying with the art historian Henri Focillon and the painter and printmaker Lucien Pissarro, McEwen decided to settle in Paris as a painter and critic; it is where he soon fell in with the artists Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Constantin Brâncuși, Graham Sutherland, Henry Moore and the art historian Georges Salles.

McEwen’s time in France had a long-lasting effect on him, and was a source of stories whenever he was playing the role of raconteur at his rooftop apartment above the gallery, where he hosted memorable parties.

(When his daughter-in-law Adele Aldridge visited together with her husband, Frank (Jnr), in 1969, they went on safari excursions to Mozambique, Wankie Game Park and the Victoria Falls. Although exciting, it “didn’t compare with the thrill of the experience of being McEwen’s guests in his natural habitat and experiencing a taste of his social life and listening to all his stories of the people he had known, such as Brâncuși, Braque, Matisse, Picasso and many others.”)

After settling in Salisbury, one of McEwen’s priorities was the speedy completion of the building in time for its first major exhibition, From Rembrandt to Picasso, to be opened by the Queen Mother on 16 July 1957. The show — featuring 350 works, including by Rembrandt, El Greco, Van Dyk, Ribera, Van Gogh, Matisse, Picasso and Moore, loaned from European museums and private collections — was a triumph, and showed McEwen at his best: he was using his old European networks and flipping through his comprehensive contacts’ book.

Despite the show being an overwhelming success, there were problems for which even McEwen’s impressive contacts were of no use: “When we sought to borrow treasures for Rhodesia from galleries in Europe, they asked, ‘Where is Rhodesia and [on] what continent?’ The reply ‘central Africa’ brought panic to the imagination of would-be benefactors — visions of fly-ridden jungle swamps seething with crocodiles discouraged them.”

The next year, 1958, the busy McEwen inaugurated what came to be known as the Workshop School — an art centre right at the gallery, at which his gallery assistant, Rowena Pearce, gave attendants paint, brushes and canvases and where they were introduced to the rudiments of painting.

Mubayi preferred working with verdite, a green metamorphic rock that has become hard to obtain. This might be because of the stone’s industrial use: when ground, its particles are used to make sandpaper. (Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe)

Mubayi preferred working with verdite, a green metamorphic rock that has become hard to obtain. This might be because of the stone’s industrial use: when ground, its particles are used to make sandpaper. (Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe)

The Workshop School — about which he wrote, “From the beginning it was obvious also that, in a country where there was not art, neither traditional nor contemporary, a school must be made to arouse latent talents and to form a new, nontraditional culture” — in some ways evinced McEwen’s paternalism.

Some of the people who joined the school include Joseph Ndandarika; Thomas Mukarombgwa; Nicholas Mukomberanwa; Moses Masaya; Lazarus Takawira’s two brothers, Bernard and John; Sylvester Mubayi; Joram Mariga and the multi-talented Charles Fernando, also a jazz musician, who, on seeing McEwen, declared: “I am Charles: I’d die for art.”

Of the Africans who came to the school, contradicting his earlier sentiments, McEwen wrote that they “showed a talent, first of all for wood carving, and then carving in local varieties of stone, notably serpentine and steatite, with immediate and dramatic success. And so was brought about a ‘renaissance’ (rather than a new birth) of the talent for stone carving, whose existence had remained dormant for and unsuspected since long before the coming [of] European civilisation to this country a hundred or so years ago”.

In some instances, some of the first-generation sculptors were also painters, but most chose to pursue stone sculpture, despite the sneers of their peers, who considered it dirty, dusty work. These men and women are, in many ways, (re)inventors of a tradition. Right at the beginning, when the stone lay across the savanna without form, without any tutorship, Mariga picked it up, chiselled it, sometimes ascribing religious function, which before had never existed (or, if it did, had been forgotten).

In the words of McEwen, the sculptors “instinctively espoused all African symbols and stylisations” common to West Africa: the big head, the sturdy sculptural legs, the chevron, the snake and other spiral symbols. “Therein may be some link with tradition, because the great birds and other objects found at [Great] Zimbabwe were of the same material,” McEwen wrote.

McEwen was wading into by then a half-century enigma, the legend of the old silent stones of Great Zimbabwe, the stone enclosures near the town of Fort Victoria (now Masvingo). Originally thought, in the words of Cecil John Rhodes, to be “an old Phoenician residence” and by some to be the wealthy Ophir region mentioned in the Bible, the provenance of the walls were believed by Rhodesians to be foreign. Rhodes believed, like many other white settlers, that the stones were of non-African authorship.

In his monumental work Great Zimbabwe, Peter S Garlake, the progressive Rhodesian-born, University of Cape Town-trained architect and archaeologist, wrote that the belief among Rhodesians was: “The African had not got the energy, will, organisation, foresight or skill to build these walls. Indeed, he appeared so backward that it seemed that his entire race could never have accomplished the task at any period.”

In another year or two after McEwen’s arrival, nationalist sentiment crystalised, and the future nation of Zimbabwe — Dzimba Dzamabwe, houses of stones — derived a name from these same stones that Mariga, Mubayi and the Takawira brothers were already working.

When people like the nationalist Michael Mawema — reportedly the man who coined the name “Zimbabwe” — started celebrating these walls, the Rhodesian authorities downplayed their significance: “Zimbabwe is just a ruin — a silent reminder of a dead and unhappy past,” a government notice was run in the press.

In response, the English historian Terence Ranger, then based at the University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (now the University of Zimbabwe), wrote in the African Daily News: “Once we were told that Zimbabwe was too ‘civilised’ to have been built by Africans; now when the scholars have proved that it was built by Africans, we are told that it is only a ruin anyway!”

III

“Our most courageous carvers, however, even reject soapstone and work the toughest granite,” McEwen wrote. “They do not refuse the archaic technique of grinding one stone against another over a long period, producing perhaps one work a month or less.” He might have been talking about Sylvester Mubayi, a featured artist at the Zimbabwe’s pavilion at the Venice 2016 Biennale.

Sylvester Mubayi was among those artists who joined Frank McEwen’s Workshop School, inaugurated in 1958. (National Gallery of Zimbabwe)

Sylvester Mubayi was among those artists who joined Frank McEwen’s Workshop School, inaugurated in 1958. (National Gallery of Zimbabwe)

For some of the older artists, such as Mubayi, using a grinder is anathema. When I asked Mubayi, who was born in 1932 and started working as a sculptor in the late 1950s, whether he used one, he replied in his soft accents, “Yes, I do, here and there, when I am working with hard stones, but most of the work is hand work.”

He was horrified by the way young sculptors at a nearby art centre in Chitungwiza, a town to the southeast of Harare, just start off with a grinder, breaking the stone’s resistance through brutal, industrial force, whether they were working with a soft or hard stone. “Zvino art yacho haizobuda.” The art won’t come out that way.”

Mubayi prefers working with verdite, a green metamorphic rock that has become hard to obtain. This might be because of the stone’s industrial use: when ground, its particles are used to make sandpaper. Mubayi’s knowledge of stone is so extensive he might as well be a geologist: the stone serpentine, he told me, although beautiful, is sensitive to weather changes. “It will embarrass you. It will crack, especially in cold climates.”

Mubayi, who has held many exhibitions in Europe and North America, should know; his anthropomorphic figures, straddling this and the nether world, in which humans are indistinct from animals, are found in prestigious collections. In the 1980s, together with Ndandarika and Mukomberanwa, Mubayi was described by the Sunday Telegraph’s art critic, Michael Shepherd, as “three of the greatest living stone sculptors”.

That Zimbabwe produced such acclaimed stone artists, and that the Shona sculpture movement became the phenomenon it was, should come as no surprise. The sometimes monotonous savanna landscape is broken by spectacular rock formations — gargantuan granite domes that rise with abrupt majesty from the flatness below and delicately balanced rocks, placed on top of the other as if by a fastidious worker — fashioned by tectonic forces, the elements and time itself.

It’s no surprise some visitors are immediately struck by these features; one such visitor — the Ghanaian Sally Hayfron, who first went to Southern Rhodesia from Ghana in May 1960 to meet her future mother-in-law, Bona Mugabe — was enchanted by the rocks. Robert Mugabe was on holiday from his teaching post at St Mary’s Teacher Training College, Ghana, and wanted to show his mother the woman he wanted to marry.

Many decades later, remembering his first wife, Mugabe recalled her fascination with the stones and how he used to tease her: “My late wife Sally used to appreciate the balancing rocks so much and she would constantly quiz me why such features of rocks carrying other rocks were not found in her home country, Ghana. I would chide her and say we could carry a few rocks to Ghana, balance them in the same way as those in Epworth, so she could watch when she visits.”

Like Sally, McEwen was similarly bewitched by these rock outcrops, which he sometimes explored in his spare time, looking for rock paintings inscribed by the Khoisan. Overcome by the beauty of the stones, he would then enthuse about the geological formations in words borrowed from epic poetry: “Have giants made castles with them [rocks], or did the gods, simply, as they did in the Bay of Rio and in other rare places, decide to outdo the possibilities of spectacular scenic beauty with incredible fantasy?”

IV

McEwen, who died on 15 January 1994, will be remembered especially for two reasons: the Shona stone sculpture movement, which, more than anyone else, he worked tirelessly to promote in Europe and North America and Icac, the art history convention held in Salisbury in 1962.

The idea of the conference grew in Paris, much like the independence of African states, negotiated in the metropolitan centres of Europe. Four years in planning and originally slated to be held in 1960, it was moved three times, before settling for August 1962.

I have often wondered why a cultural congress of this kind was held in, of all places, Salisbury, Rhodesia, when it could have been held in a dozen other recently independent African countries; Nigeria, for one, had expressed interest in hosting the conference (In 1977, it eventually hosted the Festival of Arts and Culture (Festac); the first was in Dakar, Senegal, in 1966).

In an interview with the Evening Standard, McEwen acknowledged the anomaly: “People, familiar with art, were astounded that such a manifestation as this congress could have taken place in Salisbury. No such festival has been held in any part of Africa before.” It’s a question he attempted to address in his essay In Praise of African Art, in which he wrote that “there are no particular reasons but those of circumstances”.

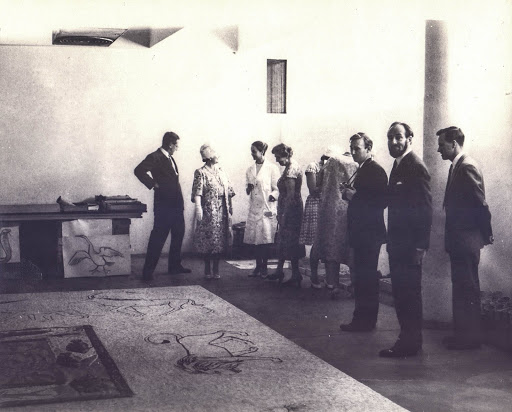

Frank McEwen (second from right), who was the director of the Rhodes National Gallery (now the National Gallery of Zimbabwe) from 1957 to 1972, is credited with promoting Shona stone art in the West. (Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe)

Frank McEwen (second from right), who was the director of the Rhodes National Gallery (now the National Gallery of Zimbabwe) from 1957 to 1972, is credited with promoting Shona stone art in the West. (Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe)

By the time the conference was held, Rhodesian politics had taken a right-wing turn and Ian Smith, a young MP and future prime minister of Rhodesia, was becoming a major player on the political scene. Far from embracing “the winds of change” that British prime minister Harold MacMillan had spoken about in his 3 February 1960 speech in the parliament in Cape Town, white Rhodesians were erecting barriers and walls to block these said winds.

The Liquor Act of 1959 had allowed Africans to drink European liquor — older, Shona-speaking Zimbabweans still call lager, wines and whiskey hwahwa hwechirungu, white people’s alcohol — but hotels and cafés, realising the mixing that would happen as Africans drank “white people’s liquor”, found loopholes to disregard the law.

With attitudes like this increasingly becoming mainstream, it’s easy to see why McEwen’s ideas about the central place of African art in European modernism were considered dangerous for a hierarchy built on the idea that Europeans were the only source of civilisation.

“The great attribute of African traditional art is expressionism and the Africans had it centuries ago,” McEwen told Time magazine. “The entire modern movement in Western art owes a debt to primitive Africa, and that is the point we are trying to make with this exhibition.”

In an essay, he elaborated this point: “It is not by hazard that Cezanne, suffering birth pangs from his heroic art, came partly from the geometrically minded Poussin and led the way to Cubism. The Picasso group was dominated by Cezanne. It flirted with African art and Cubism was begat. These activities came as early as in 1907, and they foreshadowed the Mechanical Age, the Age of Mechanical Art and that remote but rhythmically adjacent domain of African Culture.

“For does not the rhythm of the machine unite with the solemn or frenzied thumping of drums — and the drum with the beating of the heart. We are on the verge of many discoveries. We must broaden our minds to accept them, because they will be at once scientific, spiritual and artistic: things not dreamt of in our materialist philosophy.

V

One of the guests of the conference-cum-exhibition, which began on 1 August and ran until 30 September 1962, was Sally Mugabe’s compatriot, Vincent Kofi, a sculptor whose presence in Salisbury became known beyond the town’s small artistic milieu. This was not because of his work, but petty Rhodesian racism.

The Ghanaian had been working in the gallery and felt he needed some caffeine. “Some of the European girls working at the gallery said they were going for coffee and invited me along. They went ahead, but when I tried to join them, the people in the café said they could not serve me.” Despite the passage of the Liquor Act of 1959, there was “no coffee for Kofi”, as one newspaper memorably summed up the sorry episode.

Kofi was in Salisbury, a guest at Icac, the result of the painstaking work that began in 1959, after the Gallery’s board of directors approved the project, themed the Festival of African and Neo-African Art and Music and Influences on the Western World. The provisional organising committee of the conference had McEwen himself as secretary; the journalist Nathan Shamuyarira, later an academic and nationalist, was the festival’s press officer; the journalist Hosea Mapondera, ordinarily the gallery’s librarian, was doubling up as the conference’s public relations officer; Antony Howarth was the treasurer and Jennifer Dewhirst Smith was the exhibitions officer.

As soon as the board gave him the permission to go ahead with project, McEwen began consulting with some of the grandees of the art world, including Bernard Fagg, a British curator and archaeologist and the man who founded the National Museum of Jos; Alfred Barr, of Museum of Modern Art (Moma) and the authority on Pablo Picasso; Ulli Beier, the German editor and scholar, founder of the magazine Black Orpheus and co-founder of the Mbari Artists and Writers Group that had in its number people like Wole Soyinka and Chinua Achebe; Kwabena Nketia, an acclaimed Ghanaian composer and ethnomusicologist; Pancho Guedes, Mozambique’s most important architect; Tristan Tzara, poet, artist and the founder of the Dada movement; Robert Goldwater of the Museum of Primitive Art, New York.

Seventy delegates were to be invited from the continent, North, Central and South America, the West Indies and Europe to present papers and take part in the general activities of the conference. Some of the guests at the conference included Hugh Tracey, director of the International Library of African Music and founder of the African Music Society; Selby Mvusi, a South African artist who had lived in Southern Rhodesia before getting an appointment at the School of Fine Art at the Kwame Nkrumah University in Kumasi, Ghana; and the Trinidadian dancer and choreographer Percy Borde and his wife Pearl Primus, herself also an accomplished dancer.

Some of the institutions represented at the gallery include the University of Ife, the British Museum, Moma, the Institute of Contemporary Arts, the Sorbonne and the Houston Museum.

A lot of the legwork — writing of letters, travel to meetings with bureaucrats to secure artworks and publicity — was done by Mapondera, a descendant of the great nomadic rebel chief Mapondera, active from 1894 until a decade later, when he was captured by British settlers. As an African, it was easy for Mapondera’s descendant to talk to officials in the West African states — especially Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire — where they must have felt strongly the anomaly of a racist country holding such a festival.

The main exhibition comprised 100 masterpieces of ancient African sculpture, ranging from the terracotta pieces of Nok culture, dating from 2 000 years ago, to the Benin empire bronzes of between the 15th and 19th century, which signalled the shift from realism to expressionism. There were also some pieces of wood carvings of just 50 years old.

The main show was accompanied by satellite exhibitions, which demonstrated “African influences on the School of Paris and consequent influences on international schools”; “African influences in Brazil”; “African influences in the West Indies”; “African influences on North American Negro art” and “contemporary African art from most parts of Africa (south of the Sahara).”

There was a component of music to the festival, which had recitals by drummers from western Nigeria, Timbila artists from Mozambique, local mbira players, Kwela music, and mineworkers’ bands. Other neo-African music came from Brazil, Cuba, Trinidad and Tobago; and jazz from the US.

VI

It was the Nigerian historian Saburi Oladeni Biobaku, pro-vice chancellor of the University of Ife and director of its Institute of African Studies, who gave the opening address: “One of the fallacies of the modern world is to have persisted for too long in the belief that Africa was the dark continent in the sense that she was primitive in every way, backward and superstition-ridden, the abode of abysmal ignorance and debilitating disease. In short, civilisation had skipped Africa altogether; culture and regeneration must come to her from the outside.”

Probably referring to Hegel, who discounted Africans from history, Biobaku noted that, “Despised and condemned, some even said that Africa had no history; no past.”

Biobaku had not much interest in dwelling on those whose mission was denigrating Africa: “Those who planned this festival conceived a great idea and this, I suggest, is to refute past misrepresentations and place Africa in its true perspective. To us Africans, whenever we have had the opportunity to freely express ourselves, we have never doubted that we had and still have our own culture. Culture is as indispensable to a human being as a soul. For long, however, no one would believe our protestations.”

The Nigerian was quick to emphasise that this “reassertion of our own culture … is not supposed to take place in isolation, nor do we in Nigeria intend by it any notion of cultural chauvinism”. A member of the Antiquities Commission in his native Nigeria, Biobaku was backing his talk with action by giving his assent for some prized masterpieces to be allowed to be loaned for the Icac exhibition.

Biobaku observed that more studies were needed to “unfold the full story of African cultural contributions.” Already, he added some of the masterpieces Africa had given to the world were “now gaining wide recognition.” He then name-checked the bronzes of Benin, the terracottas of Ife, and pieces from the Nok culture.

In this roll call, while in the stone country itself, there was no way he was not going to mention Great Zimbabwe, some 300km south from where he stood. “And in this country the Zimbabwe monuments are receiving worldwide attention in scholarly circles.”

One of the people who addressed the conference was Tzara, the Dadaist, whose speech was concise. “It was in 1916,” just a year after his arrival in Zurich, Switzerland, from Bucharest, in his native Romania, “that I came into contact with the first works of African art. I would say at the time it was a rarity; few people even knew what it was; there was great confusion; very little was known about it. But it opened very extraordinary horizons to us and even then we were saying that African art must not be considered from the angle of curiosity, but should merit the same attention as archaic Greek sculpture or another sculpture of very great art.

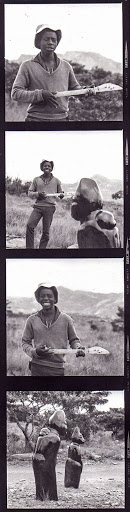

Joram Mariga is viewed as the 20th century (re)founder of the ancient artform of stone sculpting. (Image courtesy of National Gallery of Zimbabwe)

Joram Mariga is viewed as the 20th century (re)founder of the ancient artform of stone sculpting. (Image courtesy of National Gallery of Zimbabwe)“If I had known in 1916 that I would be among you today in Salisbury, where a magnificent exhibition of African art is taking place, where questions of very great importance are now being discussed. Had I known that Africa has become for us today a centre of interest, whereas at the time — towards 1916 or 1920 — it was a distant continent; very, very little news reached us from this country, from these countries, of which one knew the names and had some ideas, of course.

“Had I known that today so much mingling is taking place between occidental art and African art and culture, which is representative of the modern world and of which one had absolutely no idea at the time. Well, I am happy to find myself among you..” By December of the following year, Tzara was dead.

Next up to speak was Alfred Barr, of Moma, who started by apologising that he wasn’t suited for the task at hand. Barr was in Rhodesia, he said, “under false pretences”, because James Johnson Sweeney, who had curated Moma’s African art exhibition and Robert Goldwater, formerly of Moma but then with the Museum of Primitive Art in New York, had been unable to attend the gathering.

Barr began by referring to philosopher Herbert Spencer, who, in his book on the culture of the people found on the coast of Guinea, “reported that the sculpture there struck the lowest level of art”.

Spencer’s attitude towards this art, Barr observed, “is perhaps characteristic of the 19th century [attitude] towards African art” south of the Sahara. There was, to be sure, interest but it was limited to two kinds of people: scientists, which people Barr insists are the same as anthropologists; and explorers (or, in his words, “curio hunters and antiquarians”), who for the past few centuries had been bringing back “strange, barbaric images,” universally derided, from the outer ends of the Earth.

Something, however, had happened with the turn of the 20th century: “One of the great achievements of European and European-American culture is the extraordinary expansion of its taste, interest and judgment to include the art of the rest of the world.” The acceptance of “exotic art” had begun first with the art of the Far East and had then extended to the “tribal art” of Africa.

Surrounded by a few of these so-called tribesmen and tribeswomen, Barr was, naturally, self-conscious about his use of the phrase “tribal art”, even chiding himself for its use: “I sometimes question the word ‘tribal’, but we must not start debates now. We have 12 days to argue.”

This wasn’t the only problematic phrase Barr would use in that presentation. “The real discoverers of African art, aesthetically speaking, were, of course, artists.” He then mentioned Parisian painters, people like Matisse and Picasso; young artists in Dresden who called themselves “The Bridge”, a trend that continued in London with artists like Wyndham Lewis and Roger Fry.

The next 12 days were like this, when speaker after speaker (mostly white men) stood to speak about the influence of Africa on Western culture. In one lecture exploring the influence of Africa dance on Western dancing styles, the German scholar Helmut Gunther said, “It is one of the ironies of history that it was precisely when Europe seemed at the height of her power that Africa began to influence the Western world — the Africa that had appeared at any rate to have no power.”

One person who had problems with Europeans and Americans holding forth about African art was Felix Idubor, a Nigerian artist and delegate to the conference. “The most saddening aspect of the exhibition was the presentation of African art and music by foreigners. Under normal circumstances, this should have been done by the Africans themselves, who would have done it in the true perspective, having in their possession a better background of the cultural history of Africa.

“It is not my intention in this article to kill the enthusiasm with which foreigners try to appreciate our culture. In fact, I do appreciate their efforts, in spite of the fact that they have little or no knowledge of the subject. All I am trying to say is that is the prerogative of the African to take care of these things and that, I suppose, is in order.

“All this aside, however, I think it’s time for our government to establish a national gallery, which will compare favourably with the Rhodes National Gallery. This is necessary if we must arm the nation just in case the organisation would decide to hold its next exhibition in Nigeria in due course. Nigeria, without any gainsay, has the richest and most advanced culture in the continent and, as such, we should take the lead.”

White Rhodesians were not pleased, but not for the same reasons as Idubor; in a letter to the editor of the Rhodesia Herald, a certain AJ Knopp wrote that the reason there was general lack of interest in the conference among Rhodesians was the belief held by some “that everybody must for the period [of the conference] simulate an ‘arty-crafty’ outlook” and that Icac was “badly timed”.

The writer cannot have been referring to the weather of a country that some insisted was the best in the world. Rhodesian winters, from May to July, were winters only in name and even the winds of August could not have been disruptive for a gathering dominated by indoor talks and discussions.

At the end of the letter, we see the real, and, to white Rhodesians, frightening import of what the writer really meant by bad timing: “People are genuinely interested in art, but not when they have had a surfeit of nationalistic activity such as ‘let us go back to traditional foods — take off our shoes — bring back the witch doctors’ bones, and last but not least, get rid of industry.”

VII

A growing trend in Zimbabwean nationalism, totally unrelated to the conference which, incidentally, Robert Mugabe attended, was the rejection of the symbols of the white man’s civilisation, activities devised and directed by the former teacher-turned-nationalist. Mugabe, it turned out, had an innate ability to inspire and organise and was by then the publicity secretary of the National Democratic Party (NDP).

The party had assigned him the role of organising what Nathan Shamuyarira called “a semi-militant youth wing” — a kind of a vanguard within the party. The nationalist youth agitated for the return of old Africa: the thudding of drums, ululation by women, the wearing of traditional costumes such as leopard-skin hats, and ancestral prayer chants.

In the 1960s, seven decades after the colonial encounter, Sundays were marked mainly by two rituals: women went to church, while men sat at the council-owned taverns where they drank the traditional sorghum brew. On 3 December 1962, a few months after Icac, the NDP met in Highfield for the last time before the party was banned; it proved to be a gathering thick with emotion and symbolism.

At the Cyril Jennings Hall, in the Salisbury township of Highfield, in a gesture in which Mugabe involved ordinary Zimbabweans in nationalism, Mugabe’s youth ordered the attendants, estimated to be between 15 000 and 20 000, to take off their shoes, ties and jackets, symbolic of their rejection of European civilisation.

Those who were thirsty would be served water in clay pots which, until then, had been considered a mark of barbarity, to be used furtively, at night, at ceremonies to honour the ancestor dead. What was going on was reminiscent of Heathcliff, who, in Emily Brontë’s great novel Wuthering Heights, cried out: “I shall be dirty as I please, and I like to be dirty, and I will be dirty.”

Shamuyarira would later write in Crisis in Rhodesia, “The emotional impact of such gatherings went far beyond claiming to rule the country — it was an ordinary man’s participation in creating something new, a new nation.”

Mugabe, cultural theorist of the revolution, told the people, “Today you have removed your shoes. Tomorrow you may be called upon to destroy them altogether or to perform other acts of self-denial.” These symbolic acts were the next chapter in the story of the awakening of nationalist consciousness in the country, seeming to invoke the “despairing turn towards his unknown roots and to lose himself at whatever cost in his own barbarous people”, which Frantz Fanon writes about in The Wretched of the Earth.

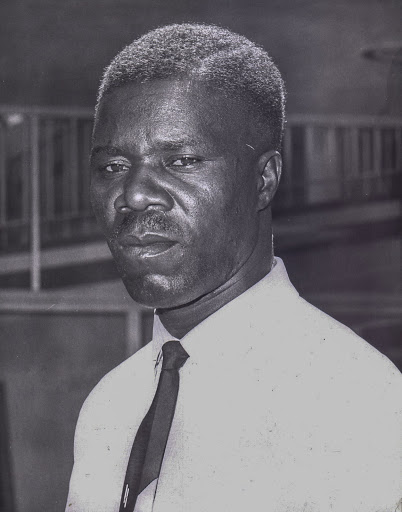

Lazarus Takawira’s brothers, John (above) and Bernard, came to be celebrated artists and key figures in the artistic school more commonly and, misleadingly, known as Shona sculpture — misleading because many of the artists were not Shona-speaking. (Courtesy of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe)

Lazarus Takawira’s brothers, John (above) and Bernard, came to be celebrated artists and key figures in the artistic school more commonly and, misleadingly, known as Shona sculpture — misleading because many of the artists were not Shona-speaking. (Courtesy of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe)

If history remembered the name Robert Mugabe and not that of Frank McEwen, it is because of the struggle that the former led in the decade to come and the latter’s decision, tired and sick of the country’s toxic politics, to leave the country in 1973 and live in a boat off the island of Bahamas.

Even though McEwen quit the gallery a decade after the conference, what I might call his parting shot was delivered during the 1962 conference, when he called out the editor of the Rhodesia Herald for the newspaper’s disinterested coverage of the conference: “If you want respect, and you need it, try and do your part of this duty; we will do ours. The international press is responding admirably to the gallery’s work and always has done. Where is the village mentality, Mr Editor? It only remains in one place, like a Victorian monocle encrusted in your brain.”

After McEwen’s departure, the struggle for liberation intensified, and Shona stone art suffered before flourishing after independence. By then Mubayi, Ndandarika and Mukomberanwa had come into their own.

Takawira had walked away from the warmth of his mother’s hearth, confronted head on the intimidating example set by his brothers Bernard and John, and quit his day job as a cop to become an acclaimed sculptor in his own right. Takawira is now shrouded in silence, as in the poem Zimbabwe (After the ruins), by Musa Zimunya, who wrote: “I want to worship Stone/ because it is Silence/ I want to worship Rock, so hallowed be its silence/ for in the beginning there was silence/ and we all were/ and in the end there will be silence and in the end we all will be.”

Attempts to establish the names of Lazarus Takawira’s mother and wife were futile.