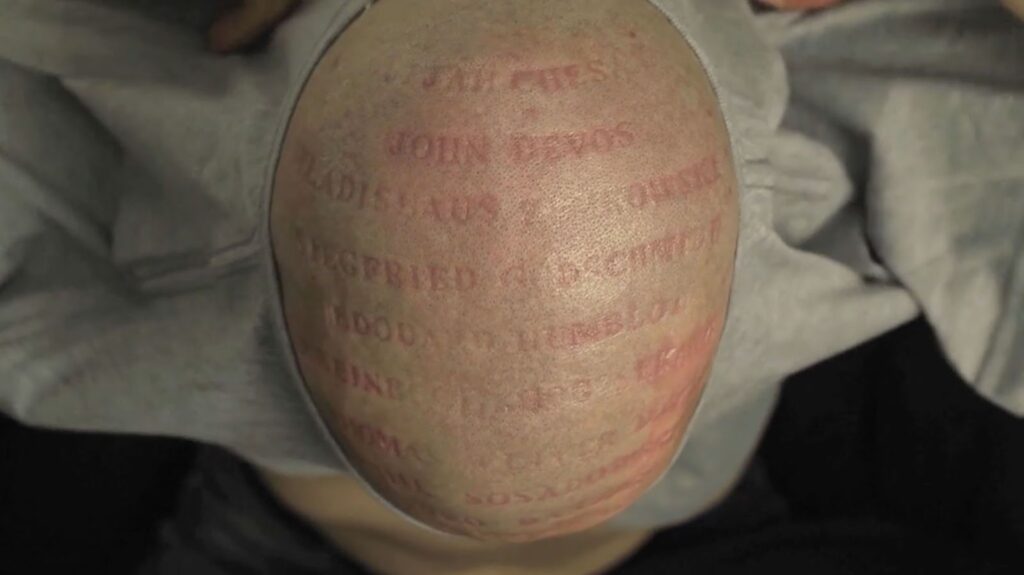

A still image from Paul Emmanuel’s ‘Remember Dismember’, a cyclical video looped so as to have no “beginning” or “end”

Over the years, reflections on June 16 have shown that this historic day is fast becoming something akin to a “burnt book”. I liberally borrow the notion of a “burnt book” from Talmudic Jewish religious scholarship’s central thesis that the burning of sacred texts often gives rise to their endurance and timeless evocation.

Academic and poet Patrick Pritchett argues that although the Jews had their libraries burnt, the “burnt book” is not necessarily “an emblem” of this horror. Instead, it “embodies redemption through negation”. Memorialisation of Auschwitz and other massacres tells us that it is impossible to erase the collective memory of crimes committed against humanity.

This is how I look at the story of the June 16 Soweto students’ riots, and the specific importance of artists and critical thinkers as keepers of our collective memory. When we rebel and part ways with the barbarism of the apartheid and democratic state, we will keep the memory of this historic event alive for current and future generations. This task is also about self-redemption and is life-giving. It is a rebellious gesture against those who, in poet Mazisi Kunene’s words, are “blinded by their own discoveries of power”.

Theodor Adorno, in his reflections on writing poetry after Auschwitz, rightly warns against the dangers of a “self-satisfied contemplation” in favour of a poetics that first and foremost sees itself as tainted by the barbarism of its age. As artists and thinkers of all stripes, the urgent task is to disrupt any stupefying ideas of national manners at the dinner table of the co-opted and the wilfully ignorant. What matters the most is what the black feminist scholar, Patricia Hill Collins, calls the kind of activism that is more than just big talk. But a way of “trying to make a difference in people’s lives”.

To look back at the sociocultural conditions that gave birth to the fires of 16 June 1976 moment 45 years ago is to rebel against wilful ignorance so brazen in the governing ANC. It was therefore not surprising when President Cyril Ramaphosa did not mention the gallant youth of Soweto ’76 in his State of the Nation address in February. The names of Tsietsi Mashinini, Khotso Seatlholo, Sibongile Mthembu (now Mkhabela) and the murdered children Hector Pieterson and Hastings Ndlovu were absent.

Paul Emmanuel “performs the dismembering of history” by donning parts of nine uniforms worn by soldiers, diplomats or businessmen that serve to trace South Africa’s military history from the Union that fought in WWI through the militarised apartheid state of mid-century to today’s neo-liberal capitalist democracy.

Paul Emmanuel “performs the dismembering of history” by donning parts of nine uniforms worn by soldiers, diplomats or businessmen that serve to trace South Africa’s military history from the Union that fought in WWI through the militarised apartheid state of mid-century to today’s neo-liberal capitalist democracy.The 45th anniversary of this important chapter in South Africa’s quest for freedom from colonialism and the shackles of apartheid came in the wake of the deadly Covid-19 pandemic, a worsening economic strife, the looting of state coffers and rolling blackouts. This series of heady stuff preoccupying the minds of most South Africans partly explains why that dark day of the murder of black youths in 1976 was, with minor exceptions, a low-key affair. But the amnesia and subtle obliteration of this historical landmark at the upper echelons of the people’s government has been a recurring feature since 1994. Many people who care deeply about this political moment are now accustomed to off-the-mark headlines regarding June 16, such as president Thabo Mbeki’s humiliation of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela at Orlando Stadium in 2001.

Party-loving and boozing youths have also become a familiar sight in state-funded gumbas through which large sums of money have been plundered from the national purse. No wonder the diminishing significance of June 16 in the nation’s public imagination has only worsened.

This week’s national commemorations, while only partly salvaged by a desire to tackle spiralling youth unemployment, were nonetheless another presidential side-show festival of mealy-mouthed gestures and other silly jigs. Contrary to the ethos and the revolutionary imperative of the young men and women who marched in Soweto 45 years ago, South Africa is replete with rigorous acts of muting the fiery emancipatory vocabularies that were key philosophical tenets of Soweto ’76.

Clearly, as Innocentia Mhlambi, Heidi Brooks and Njabulo Zwane have recently observed, the post-apartheid dispensation has largely failed to advance “the local, indigenous cultural forms” of being and knowledge production. The point being made here is important because it helps in articulating an expanded reading of the textual and political import of the Soweto ’76 riots, and not only looking at them as an anti-Afrikaans language insurrection. Such a reading, as Joel Netshitenzhe puts it; is essentially asserting “indigenous culture which was previously suppressed”. What Netshitenzhe suggests is in line with looking at the previous sociocultural abuses of language, and in Helena Pohlandt-McCormick’s words, “to penetrate the silences of historical memory in South Africa”.

Working from head to toe, portions of the artist’s exposed body, inscribed with the ‘lost men’ of South Africa’s wars, appear as he robes and disrobes, thereby creating a metaphor for sections of the soldiers’ bodies that could possibly have received a mortal battle wound. (Courtesy of Paul Emmanuel)

Working from head to toe, portions of the artist’s exposed body, inscribed with the ‘lost men’ of South Africa’s wars, appear as he robes and disrobes, thereby creating a metaphor for sections of the soldiers’ bodies that could possibly have received a mortal battle wound. (Courtesy of Paul Emmanuel)

Pohlandt-McCormick’s counsel also speaks to the need to confront the country’s stubborn spectre of political violence as language and a way of life. “Violence may be subtle or blatant, but it was an integral part also of historical and political thought in South Africa. It manifested itself in political and everyday language, in the way evidence was destroyed or concealed, and in the way its material and discursive reality shaped the telling of stories, what could be remembered and articulated …”

But memory, as the historian Sifiso Ndlovu attests in the case of the Hector Pieterson Museum in Soweto, “rarely goes uncontested”. Ndlovu says that as a “never again” project, such memory “runs up against competing memory projects including of outright denial or interpretive justification of the violent past often articulated by white South Africans”.

This week’s solo performance art by Johannesburg visual artist Paul Emmanuel, a gay man of Lebanese and South African parentage, is in this mould of “fresh” resistance. Emmanuel projected his “white body onto the General Louis Botha monument, because on my skin I have remains of the men who died in all the battles that South Africa has taken part in.” Comprising nine pre-shot video scenes projected on the wall of Botha’s monument at the Union Buildings in Pretoria, he was visiting South Africa’s archive of blood-letting and the tyranny of mainly white men from World War I to the Marikana massacre.

Remember-dismember (2015) from Paul Emmanuel on Vimeo.

Titled Remember-dismember, the work is concerned that, “if there is a distorted version of history, this is a form of dismemberment. I am taking on and putting off, putting on and taking off, all the uniforms that white men have worn over the years. In one of them, I even put on and put off an executive business suit. There are a lot of design similarities between military uniforms and European business suits. It is a uniform and a form of armour.”

Emmanuel is also tackling the issue of toxic masculinity and “how society constructs ideas on what it means to be a man. Because of my sexuality, I have struggled with that for a long time.”

This is the time to be mad. We need new poems. As Lesego Rampolokeng shows in his forthcoming Bavino Bachana Mixtape, these poems are not from a familiar and warm rainbow land. Rampolokeng is in full flight, re-imagining South Africa’s ills with his unrelenting visceral register.

“idiotic sick

take patriotic stand in

this land

perineal area

between gonorrhea & perennial diarrhoea

this land

built on digging &

salt-panning humans

walking trenches

mine-dumped veins

sand-senses

this land

caprivi-stripped down

to the skeleton

this land rattles on …”