Jabba performing at Back To The City festival in 2016. (Photo: Tseliso Monaheng)

It’s close to midnight in Cape Town. Hip Hop Pantsula is on stage, drenched, rapping about financial power, not believing everything you read in the paper and, curiously, erstwhile Gauteng premier Mbhazima Shilowa, to a fully packed Zula Bar, located on Long Street.

He continues to fire up a series of impactful lyrical missiles at what Peter Tosh calls the shitstem as his DJ, Hamma, slices ’n’ dices up a bare bones dancehall riddim on the decks. “Government-e dam a run like the mafia run ting, dem ah always wanting that they’re above the law, they are wrong, dem gwaan pay, in the bed that they done made, they gwaan lay,” he raps.

In hindsight, it was an odd event, somewhat. Jabulani Tsambo — or Jabba or HHP, short for Hip Hop Pantsula — was one of the biggest artists in Mzansi, among the best MCs on the African continent, and the best crowd controller bar none. That he’d been booked for a show at a moderately sized club renowned for its consistent support of independent artists was special beyond measure.

“Before we even start this track, I’ve just had the worst month ever, man. I’ve just had my own bullshit happening in the month; there’s just so much that is going down,” he shared. Hamma cued up the self-love mantra, Get Up, from the South African Music Award-winning Acceptance Speech, released in 2007, the same year HHP and dance partner Hayley Bennett were crowned overall winners on SABC2’s Strictly Come Dancing.

The Zula Bar performance, which happened in 2009, was memorable because HHP had broken through to an audience that was neither rap nor kwaito, nor house. He was making music with PJ Powers, guesting on shows at Kirstenbosch Gardens with Lira and, later, hosting his own television programme.

HHP, aka Jabba, performing at the Maftown Heights festival. (Photo: Tseliso Monaheng)

HHP, aka Jabba, performing at the Maftown Heights festival. (Photo: Tseliso Monaheng)Years later, when his star had somewhat waned due to an influx of new talent, and a sonic landscape that had swung in favour of trap music, I paid HHP a visit. He was frustrated by the state of rap; he was tired of fighting online trolls daily; and he’d gone on Cliff Central to speak about the times he’d attempted suicide.

We found him in relaxed work mode. His skeleton band was around, and they were running through songs for an upcoming show. He made time for conversation in between rehearsals.

“I’ll be honest: Jabba died. This new Jabba is someone else,” he said. “I’m happy to be alive. One thing that [made me depressed] was having to live a double life. I hate that celebrity lifestyle. One of the reasons why I’m rapping, is I was really hoping to be a Maftown hero. I think Maftown’s been wanting a hero for so long, and I was sure that Cassper [Nyovest]’s [gonna be that]. But Cassper’s now like, he’s out there, he’s in the world now, and Maftown still needs a hero. We still need a Superman.”

The statement was at odds with how he’d come to be perceived in the context of South African hip-hop. Jabba was a hometown hero, who never forgot to mention both his province, North West — “Ha o na le mona boss, dimma/ we’ve been hungry for long, and all along le re tima/ now le batla ho re skeem-a/ we always pledge allegiance to Bokone-Bophirima” — and his birthplace, Mafikeng — “It’s a lessons for my niggaz all over to get down/ all my women feeling jiggy from Jozi to Cape Town/ if o ikutlwa mafolo-folo then come down, to mahipi a Tlhabane and Maftown”.

Jabba started out as part of rap crew Verbal Assassins, and then transitioned into a solo artist, undergoing many a rebrand before his 2004 breakthrough, Harambe. He formulated a style, an approach, and a movement unseen in rap up to that point in history. Motswako artists of that era, from Morafe and Molemi, to Tuks and JR, have the visionary HHP to thank for carving and maintaining a lane.

“We’re living HHP’s dream. Everything that’s happened, he predicted. It sounded like all kinds of gibberish back then. Big up to him,” said Khuli Chana during an interview on location for the filming of the Hape le Hape 2.1 music video. Jabba was gone by the time Khuli and I spoke on the eve of his third album, Planet of the Have Nots.

“Motswako, as a movement, I feel like it hit a ceiling, and especially after Jabba. A good friend of mine asked me a question at the funeral: ‘Now that we’ve laid broer, do you think it’s the end of an era, or the end of a chapter?’ And that’s the question that Jabba has left us with. He carried that torch man, like you don’t understand. When [Morafe was] coming up, Jabba moved with us. He consciously made us shine. He also became the reason we peaked,” Chana recalled. “So when we were bubbling under, that guy would randomly jump on stage as a surprise on our show. So you’ve got this giant on stage with you, you give him the mic and he’s singing your hooks. When he does shows, he’s singing the Morafe hooks, he spits Khuli Chana verses. He plugged us hard.”

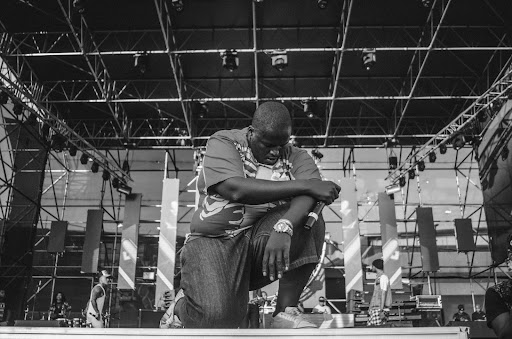

Jabba kneels before the Back to the City audience in Newtown, 2016. (Photo: Tseliso Monaheng)

Jabba kneels before the Back to the City audience in Newtown, 2016. (Photo: Tseliso Monaheng)

Yet all that sceptre-wielding, energy-siphoning dedication had fallen by the wayside when the new school of rap found comfort in the spotlight. “People kinda heard that Cliff Central interview and stuck to the wrong thing,” Jabba said that one time at his home. “I wasn’t there to talk about that shit. For me, it doesn’t say that Jabba’s seeking attention; that’s what people think. I think to me, it says that there are so many people who try the same thing, that this [revelation was] a big deal to them. Like, I tried to kill myself too. I mean, I took five Panados, but like, a lot of people go through depression.

“One thing that’s powerful about what’s going on is that people are forgetting that we’re all human. They get so exposed when you tell the truth. It’s a beautiful thing to be alive right now, and to be Jabba. Right now, I’m all about Jesus Christ man. That brother, he literally saved my life. I feel like in that last suicide attempt, he kinda said to me: ‘Look man, first of all, you’re a dumb ass nigga, because you’re not dying. I sent you here for a reason. Secondly, you know you’ve just committed the biggest cardinal sin, fam. So you can either die and go to hell, or I come and take over.’ And I just started doing shit my way.”

The rapper was found dead on 24 October, 2018, just more than two years after our visit.

At Zula, HHP ran through his vast discography, comprising party starters (Bosso, Let Me Be) and socially tinged joints (Harambe, Hell Pon Me); at no moment did he lose the audience. Instead, he set a bar that he consistently passed. He incorporated his quirky dance moves and ticked all of the required boxes. He had the whole joint hanging by the thread of every bar, shouting and screaming back phrases on cue. It was impossible to imagine a future without grootman, but here we are.

Although he might be gone, his legacy remains — in songs, and in the strides he made to ensure that the Motswako baton is passed on from one generation to the next. The reason there is a Cassper Nyovest, a Maglera Doe Boy, a Focalistic, or a Steeno le Twenny, is because Jabbaman took flight from where Stoan and Baphixile had left off, and created an empire. This is but a small portion of what he did, for he is an artist that defied categorisation, and a man whose warm personality represented a boundless capacity to give.

For all the parts that Jabba lost in pursuit of greatness; for all the times the music industry forgot his contributions, we remember.