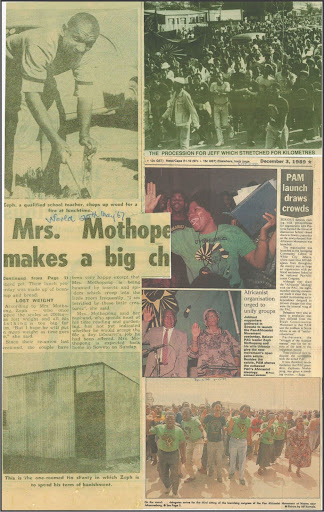

Uncompromising: Zeph Mothopeng was the president of the PAC from 1986 until his death in 1990. (Photo: Patrick Durand/Sygma via Getty Images

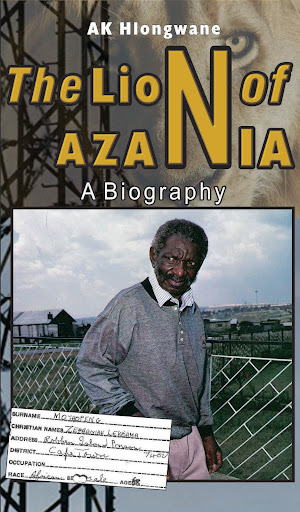

This year marks the 31st anniversary of the death of the former Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) of Azania president Zephania Lekoame Mothopeng. Sizing up his legacy will be a mammoth task, given what Tom Lodge says about public lives in The Lion of Azania: A Biography by Ali Hlongwane: “Lives lived solely for the struggle may be virtuous, but they are hard to embody as flesh and blood.”

For biographer Hlongwane, this has been a lifelong study, having lapped up the teachings of Mothopeng as a youth in the PAC structure the Azanian National Youth Unity (Azanyu) in the 1980s. The researcher consolidated his study as a master’s student at the University of the Witwatersrand and the book grew from those studies.

The biography reads like a love story between Uncle Zeph and his wife, Urbania Bebe Mothopeng (née Lonake). In an interview with the author, she exclaims: “That chap suffered a great deal.” She could be referring to both the political and the personal. Her husband was one of the most tortured prisoners in the country.

But Urbania, who would also become a leader, having to see to the formation of the African Women’s Organisation, is referring to the reluctance she displayed when Mothopeng made it known that he wanted a relationship. Her positive response came three years later in the form of a letter. This would begin a journey of one of the “happiest married couples in the world”.

Uncle Zeph paid tribute to his wife after his banishment in Qwaqwa: “You have managed to keep the home fires burning against all odds and you have been a shining example to my children and I hope they will follow in your footsteps.”

The sense of foreboding probably came from the state wanting to get rid of the veteran by any means necessary. At one point the teacher inherited the name “Cobra” after a serpent charged at him in one notorious prison courtyard.

His daughter, Sheila Masote, wrote to her father listing some incidents: “There was the terrible stabbing you endured in the crown of your head from a police official at the Pretoria Central Prison; being tied hands and feet to two poles and being rolled over like a spit braai for hours on end; the electrocution and the staged ‘snake bite’ on Robben Island.”

For biographer Hlongwane, the book is the culmination of lifelong study, having been taught by Mothopeng in the Azanian National Youth Unity (Azanyu).

For biographer Hlongwane, the book is the culmination of lifelong study, having been taught by Mothopeng in the Azanian National Youth Unity (Azanyu).

At the age of 65, Mothopeng was indicted as part of the trial of the Bethal 18 in a 50-page document alleging, among other things, that “the use of violent means pertaining to urban unrest in 1976 was discussed, organised and methods to be used demonstrated.”

One writer quoted in the book dubs the trial “the Terrorism Act Trial of the 1970s”. This refers to the 16 June indictment where Soweto students ran riot against the regime.

The court roll at the secret trial included such leaders as the PAC’s founding-president Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe and chair Potlako Leballo, among others. Sobukwe is dubbed “co-conspirator number one”. Mothopeng is the number one accused, sentenced, at the end, to two 15-year terms running concurrently.

But in 1989, the government decided to release Mothopeng from prison, practically on the eve of FW de Klerk’s February 1990 speech, which saw the unbanning of the PAC, the ANC and other organisations.

Hlongwane portrayed the journey of his hero, who died on 23 October 1990, as a tragic one. He died at the time his organisation was about to pronounce on the talks (or the non-talks) with the De Klerk regime.

The question of negotiations with the De Klerk regime became sensitive when the leadership was asked at the Truth and Reconciliation Commision about the militant activities of the Azanian People’s Liberation Army during the “truce” when negotiations for a peaceful transition began.

It is clear that there was a two-sided struggle in the movement, with each faction trying to sway the other. This is where Hlongwane prefers not to tread but to leave the topic “for another day.” The hero died at the threshold of a critical decision about the future of an envisaged Socialist Republic of Azania.

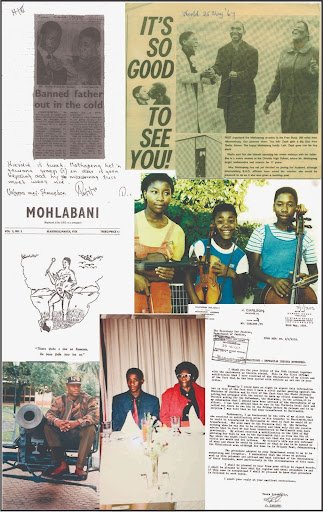

The Lion of Azania features reproductions of Mothopeng’s family records.

The Lion of Azania features reproductions of Mothopeng’s family records.

A poignant moment in the book is when veteran journalist Ameen Akhalwaya from The Indicator asks the recently released leader: “What is your message to [then-head of state] PW Botha and the people?” Mothopeng’s answer is on point: “I am going to spell it out tomorrow when I speak at Regina Mundi Church.”

The writer notes: “He didn’t do so. The commissioner of police banned the Regina Mundi meeting.” This displays Mothopeng’s uncompromising character, at least in the eyes of the minority apartheid regime.

For Mothopeng, the negotiations process was inherently contradictory. The section titled “The Method of Obtaining Reforms by Negotiation Rather than by Revolution” in the appendix states: “Negotiations must be in secret or behind closed doors. Only points of agreement must be made known. The points on which agreement has been reached can be attainable and must be implemented immediately. The reason is to hoax or lull the public in order to make them accustomed to the process of negotiation and actually believe that negotiations have succeeded.” The document is believed to have been penned by Uncle Zeph and is dated 1990.

But the leadership who supported negotiations also claimed Mothopeng’s legacy. This is based, among other things, on the Akhalwaya interview from an undated Azania News (a PAC publication). Mothopeng is asked: “In South Africa, there is some confusion about the membership of the PAC, that it is all-African. Some interpret this to mean ‘indigenous African’, while PAC leaders abroad say the PAC is nonracial, that ‘African’ means all who owe allegiance to Africa. Can you clarify?”

The freedom fighter declares: “The question of who goes to parliament will be determined by the system of one person, one vote.”

At a press conference held after De Klerk’s speech by Mothopeng and the PAC’s former secretary general, Benny Alexander (later known as Khoisan X), Mothopeng argues that the negotiations can only take place based on the “ownership of resources, particularly land as well as the question of one person, one vote in a unitary state without any minority veto powers or protectionism”.

But for the youth in the Revolutionary Watchdogs, Mothopeng was uncompromising to his last breath. They say the firebrand intimated that talks could only take place at the transference of power and the land to the indigenous peoples. This, in turn, could only happen when the liberation movement was at the height of the struggle. That moment had not arrived, argued the radicals, as they didn’t even have liberated zones in the country controlled by the movement.

Hlongwane’s biography is one of few that is comprehensive on “the Lion of Azania”, according to the reviewer

Hlongwane’s biography is one of few that is comprehensive on “the Lion of Azania”, according to the reviewerThis historical phase is the only omission in an otherwise well-researched book on an unsung hero of the struggle.

Another issue is the PAC’s position on economic policy. Hlongwane traces the portrayal of the movement being “anti-communist” as being based on its critique of the South African Communist Party (SACP), and particularly its predecessor, the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA).

The PAC favoured the postulation of the “black republic” espoused by the Communist International in 1928, which delegates of CPSA rejected. They opted for the “South Africa belongs to all who live in it” postulation later reflected in the Freedom Charter. According to Hlongwane the slapping of the anti-communist tag on the movement was unfortunate because Mothopeng himself asserted: “The premise from which I start is socialism.”

This book is one of few that is comprehensive on “the Lion of Azania”. Hlongwane is writing another biography of a former chair of the PAC, John Nyathi Pokela.

The fact that these biographies are so scarce is regrettable. We can only encourage the likes of Hlongwane to continue.

The Lion of Azania: A Biography is published by Skotaville Publishers and distributed by Jacana Media