Mermaid, Lagos, 2018. (Photo: Mike Calandra Achode, Tommaso Cassinis)

The big money fiesta of the late 1970s and early 1980s ran Nigeria into the ground. The toll of the governmental politics of those days — facilitating an urban culture of crime, vice and zero responsible public ethics, fuelled by corruption in all sectors of society — finally set in. Between 1983 and 1986, Nigeria applied for International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank loans in a structural adjustment programme that aimed to reduce the country’s fiscal imbalances. This programme required fundamental changes that included privatisation, deregulation and the reduction of trade barriers.

The first social sign of cultural decay was the disappearance of Owambes (parties). The Nigerian government no longer had any interest in promoting “frivolous” ideas. Culture and culture-related fields were no longer seen as strategically important enough or as contributing to national productivity. So, the government stopped funding culture. The National Theatre in Lagos fell into disrepair. Traditional big venues like Tafawa Balewa Square were no longer accessible, because the government, which controlled these spaces, was not interested in promoting cultural production. In general, public venues for hosting musical events began closing down. Lagos was badly hit.

The hardship and sacrifices of the structural adjustment programme required a drastic restructuring of the country’s economy. The programme caused mass unemployment, a rise in food prices, and an inflation spiral that affected many businesses, leading to their eventual liquidation. The economy’s disposable income that supported the creative arts and culture was also hit hard. This austere situation caused a migration of creative talent out of Lagos to different parts of the world, especially to the global West. The economic downturn in Lagos was so critical that virtually anyone and everyone who had the means or qualifications left Lagos for greener pastures. Record labels closed as the music business wound down. The structural adjustment programme made Lagos a terminally ill city.

Wafflesncream, 1004 Estate, Lagos, 2018. (Photo: Mike Calandra Achode, Tommaso Cassinis)

Wafflesncream, 1004 Estate, Lagos, 2018. (Photo: Mike Calandra Achode, Tommaso Cassinis)

But, at the same time, as life became tougher for Lagosians, music became the drug of choice for many people to escape reality. Its effect was more evident in shared experiences. People looked for and constructed spaces to share their stories through music. The unavailability of big venues, despite the obvious public dependency and demand for music for survival, triggered the detraditionalisation of sites of hybrid identities (the office, the home and the church) as the new sites for “clubbing”.

In particular, the Christian, song-based praise and worship tradition was a perfect channel for people to recalibrate and make meaning of the hardship they were going through. This promoted the blurring of the difference between secular and non-secular music. Once again, the church became a place of resistance — but this time through popular music production, and with the difference that this time it was not the old “African” churches but the new popular Pentecostal churches.

Fela Kuti and Africa 70, Zombie, 1976.

Fela Kuti and Africa 70, Zombie, 1976.

It was particularly in the high-density areas that Pentecostal Christianity spread, as the toll of economic reforms hit Lagos hard. Like fuji music, Pentecostal roots in Lagos lay at the behest of the poor and the needy, unlike other organised Christian religions that are not populist in nature. The Lagos Pentecostal churches positioned themselves as agents of modernity and crafted a message of success. And this was formulated through music.

Taking advantage of the mass appeal of fuji music (as a traditionally Islamic-inspired sound), the churches appropriated the speech-act performance of fuji and connected it to sacred pop (popular commercial gospel music). With this new, hybrid marriage between gospel and fuji music, the church also became the venue for popular dance — the new “nightclub” in town. It became tradition that every Friday night, young “clubbers” would now troop to a night vigil prayer worship service that lasted all night long. But even the church could not quarantine itself from the transactional nature of Lagos: many young Jagua Nanas (sex workers) found these churches fertile hunting grounds. To sum up, the churches had everything: great music, electrifying atmosphere and husband-seeking young ladies. Which nightclubs could beat this?

The battle for the soul of the common man moved to new arenas. As Christianity became widely seen as the modernising religion, and money was the reward for being religious, some churches began presenting sexy adverts that showcased a life of luxury and enjoyment. There were new battles of roadside churches versus mega churches versus megaphone-churches. In the markets, there were now mobile churches that brought the sound of the Lord to the people. Gospel secular music flourished. All these factors, the music plus success preaching and the attraction of modernity, caused a great number of former Muslims to convert to the Christian faith.

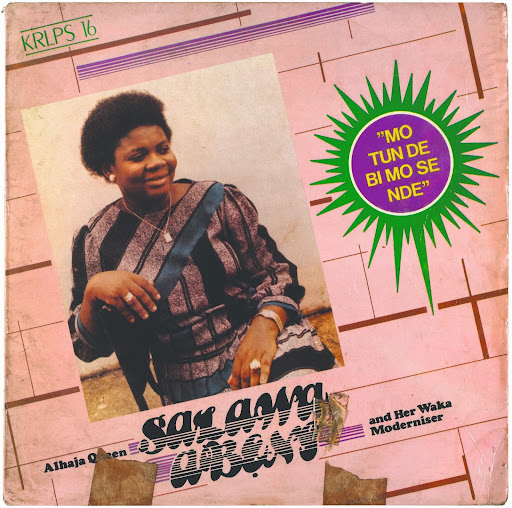

Alhaja Queen Salawa Abeni and her Waka Modeniser, Mo Tun de Bi Mo Se Nde, 1986

Alhaja Queen Salawa Abeni and her Waka Modeniser, Mo Tun de Bi Mo Se Nde, 1986

In reaction to this Christian invasion, the Muslim cultural intermediaries in Mushin, Ajegunle, and other informal urban slums extended their spiritual and musical inclinations to high-density contact zones. This came, among others, in the form of mobile billboards on public mass transit vehicles like motorcycles, tricycle motorbikes, molues (a local mass transit bus), and bolekajas (Yorùbá for “come down let’s fight”) — a rowdy half-metal, half-timber bus construction. It was aided by unregistered social networks like savvy street hawkers, who created new “musical” arenas that echoed popular lyrics, slang, and graphics from fuji music, or “area boys” (a local street subculture group of gangsters). It further institutionalised street hawking as a cultural infrastructure and an established commodity chain for music promotion, distribution and marketing.

Street hawking, which is organised and run by a cartel, became a fast way of distributing products to the mass market. The process empowered the members of these unofficial networks by revalorising their sense of participation and inclusion as citizens of the city. Interestingly, the potency of these informal networks gained the notice of Lagos politicians. The politicians started to invest in the creation and destruction of subcultural groups in the city. For example, many area boys found employment as easily mobilised thugs for political groups and government officials. When their services were needed, the area boys would be brought on. They would be returned to the street once debriefed, adequately rewarded, threatened and warned against disclosure.

In the late 1980s, while all this was happening, another process was evolving in the high-density urban area of Ajegunle, the “Jungle City”. This slum is where all the hard criminals live and hang out, like the infamous One Million Boys gang of robbers that attacked their victims with locally fabricated firearms and machetes. It is where all the real stories of the hardship of the city can be heard. It is a place that was spontaneous with its tactics and strategies for surviving Lagos. It is a place that resisted the city. According to Ajegunle’s resident philosopher, poet, musician, and activist, Aj Dagga Tolar, “Ajegunle has become a metaphor for the entirety of the Nigerian nation.” And: “It is in this part of the country that you meet the poor of the poorest, and we try to survive day in and day out.”

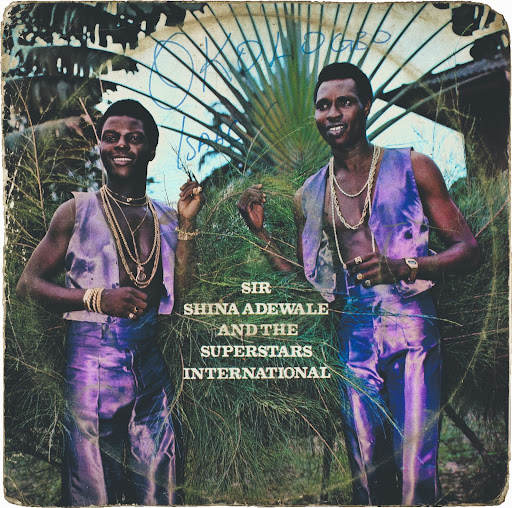

Sir Shina Adewale and the Suerstars International, 1978

Sir Shina Adewale and the Suerstars International, 1978

But Ajegunle is also an example of how failure generates opportunity given a certain form of creativity and necessity. It is in Jungle City that Lagos began its cultural regeneration after the structural adjustment programme, because Ajegunle became the main site for emerging new musical creativity, dance and performance that was all held together by its own distinctive sound. At the time the Ajegunle sound was galala, a blend of roots reggae, fuji and street slang lyrics. The lyrics of this sound were always about survival, success and salvation that spoke directly to the heart of the common Lagosian.

In Lagos, what resonated with the larger urban landscape always came from the poor social bracket. It is like this here, in Ajegunle, where cultural intermediaries like the galala musician Daddy Showkey defined the musical taste, dance and fashion of all of Lagos. For example, Daddy Showkey sagged his jeans and so did all area boys. Many area boys also adopted dreadlocks in homage to the musician. Cultural intermediaries from Ajegunle, like Daddy Showkey to fuji star Wasiu Alabi Pasuma, became role models for urban style and swagger. The Italian designer denim jeans and T-shirts they wore became the urban dress code. In the end, the area boys measured their sartorial taste based on standards of being hip set in Milan or Naples.

Ten Cities (Spector Books/Goethe-Institut), a book on clubbing in Nairobi, Cairo, Kyiv, Johannesburg, Naples, Berlin, Luanda, Lagos, Bristol and Lisbon between 1960 and March 2020, is edited by Johannes Hossfeld Etyang, Joyce Nyairo and Florian Sievers. This extract, on the economic factors driving the hybridisation of fuji music in Lagos, is the eighth in a series of 10 weekly excerpts from the book