The Good Ship Jesus, Tracey Rose, 2017. Photo: Courtesy the artist and Dan Gunn, London

On the morning of the press conference and walkabout for Tracey Rose’s first major retrospective at Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art in Cape Town in February, I was thrilled by the prospect of seeing the work of a major figure in contemporary African art whose myth preceded her. For Rose is larger than life, her mixed-media works, part photography, video, installation, digital prints — a high-octane mix of the absurd, anarchic, and carnivalesque.

Unsurprisingly, the show came with an age restriction, despite that at a click and swipe, children are exposed to the furthest reaches of depravity. Morality is passe, censorship mere smoke and mirrors. Or rather, morality is under siege, censorship a violent and reactionary bid to hold fast to bygone values. This is the volatile and extremist moment we are living in, in which Rose’s art plays an incendiary role.

Exorcism and cleansing rituals are vital thematic concerns, as are the matters of “repatriation, recompense and reckoning, post-apartheid legacies, liberation movements”, and, at their reflective and performative centre, Rose’s body — “a channel for the demonstration of exasperation, aggravation, disruption and paradox”. A heady cocktail indeed.

The Prelude: Garden Path, 2003. Photo: Courtesy the artist and Dan Gunn, London

The Prelude: Garden Path, 2003. Photo: Courtesy the artist and Dan Gunn, London

The body in art is nothing new, but in South Africa, there are very few who have chosen to make it the hammer-anvil-crux of their creative expression, perhaps because of our ongoing moral prurience, or its banal subtraction to a sign of race? After all, in this globally benighted historical moment, it is race that has once again reared its pitiful head, at the expense of all else that makes us singularly human.

A friend, instrumental in the creation of the South African Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, recently sent me two “prompts”: “Is it essential for black artists to be able to fit into traditionally white spaces to further their careers? If so, to what extent? Is it possible for black artists to remove their identity from the subject matter of their work and still thrive, or is that all people expect to see from them?” These prompts, no matter how tedious, remain vital.

In the case of Rose both are embraced and, crucially, transformed. Her gendered and raced body is the crux, as is its historical victimisation and its transmogrification, for what Rose does is invoke and transform historical pain to further complicate the conceptual and physical nature of human struggle. Protest is insufficient, performance is vital, hence the integral elements of absurdity and the carnivalesque — say, the donning of a tall papier-mâché hat in the shape of a cock and balls while mounted on a donkey, heaving clumsily through a jungle. In The Prelude: The Garden Path, the nod to imperial invasion, the deluded belief in a civilising mission, the pornography of power, and the precarity of womanhood in a white male world are all acutely in evidence.

Paradox, not didacticism, is the key to Rose’s photographs, videos and installations. Her purpose is not to tell us what to think, but to situate us, often uncomfortably, in the middle of a charged arena of mind and body. Given the predictive nature of the contemporary African art world — its market economy, over-inflation of the black body, and subsequently the diminishment of its complexity — Rose’s work, four decades in the making, remains refreshing. Why? Because it capitalises on a deep-rooted psychic unsettlement that is peculiarly South African, because it pivots and twists about a body which resists singular definition, be it gendered or raced, and all importantly, because it is a celebration of an explosive, inflammatory, provocative, outrageous artist.

Rose is that rare creature, someone who never hesitates, who galvanises the corrupted paradox of creative expression. In her introductory speech for the show, Koyo Kouoh, the executive director of Zeitz Mocaa, isolated a single word to define Rose’s work — rage. Rose, she says, is an “enraged artist … a South African citizen, a woman, in rage”. Hers is “a cry for respect, for liberation — a productive rage”. The politics of the body and nationhood are inextricably bonded, Rose’s “productive” anger understood as a potent reckoning, because as Kouoh understands it, Rose’s anger is never merely reactive. She does not fight against a problem but produces the possibility for its correction and transformation.

In South Africa, a country built on reactive rage, immune to criticism, violently absolutist — indeed nihilistic — what Rose offers is a mechanism and means through which to thread human complexity. If history meets the body politic, so does “conspiracy, dream and desire”. In Rose’s world the material and psychological, conceptual and emotive are one. That Kouoh and Rose have a relationship spanning two decades and counting — they first met at the Dakar Biennale in 2000 — further underscores the depth of their collaboration. That Kouoh is adamant in her focus on in-depth individually-fuelled exhibitions are, in this regard, a vital wager. For what troubles Kouoh is the perception of black artists as a collective. Why, she asks, are group shows devoted to otherness ubiquitous? Why is it so difficult to recognise a black African artist as a singularity?

Rose refuses “to simplify reality for the sake of clarity”. This resistance runs against the dominant dogmatic culture. Her satirical strategy, mired in calculated paradox, resists “the narrative of struggle and reconciliation”. Two enshrined values are contested here — the belief that sequential constructs lead to truth, and that, through this discursive process one can reconcile the wounds of history. That Rose is critical of Nelson Mandela’s reconciliatory politics underscores this pervasive doubt. We remain arrested, intestate, appallingly broken as a nation. That said, Rose is careful to remind us that she is no nationalist. Her vision echoes that of Kouoh, for whom “South Africa is a name to understand the world and the human condition”. Their shared vision is global yet local, all-encompassing yet ruthlessly particular. And it was none other than Steve Bantu Biko who shared Kouoh and Rose’s advocacy, declaring in I Write What I Like that Africa would gift the world with a “human face”. Despite all evidence to the contrary — a reversion to barbarism, here and abroad — I remain convinced that Biko was right. Rose’s explosive retrospective is its brilliant answer.

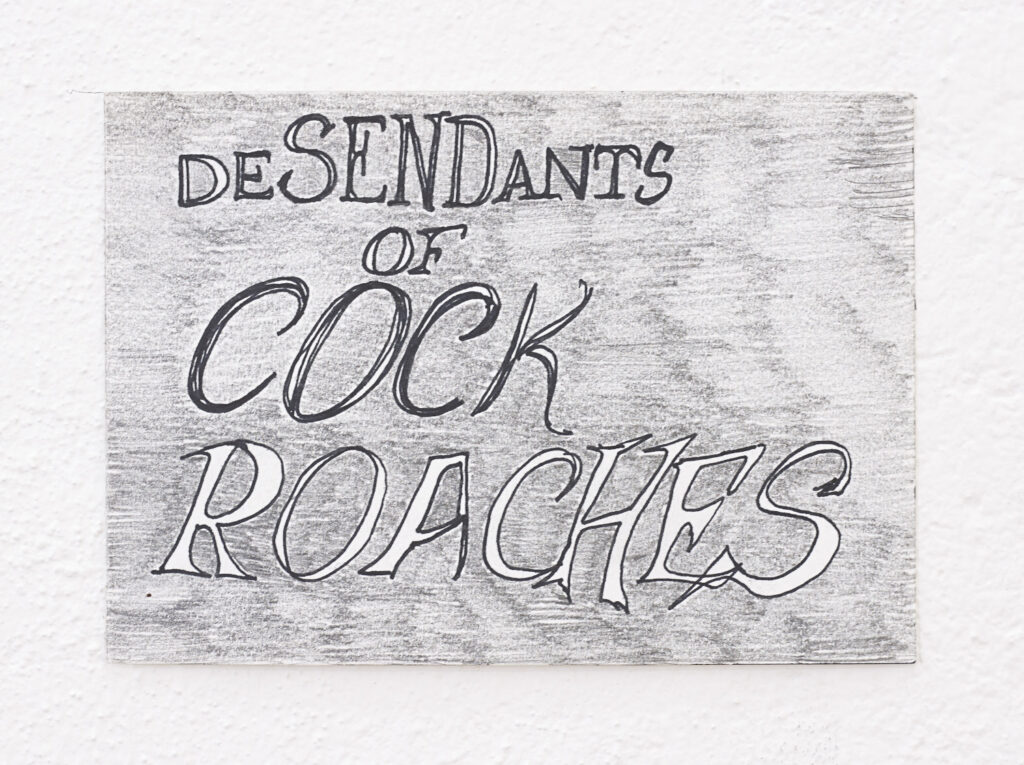

From The Good Ship Jesus, 2017. Photo: Courtesy the artist and Dan Gunn, London

From The Good Ship Jesus, 2017. Photo: Courtesy the artist and Dan Gunn, London

“As long as we can keep talking, we are not killing each other,” says Rose. The sentiment is salutary, but it is also dangerously at risk, precisely because we no longer speak to each other, because we have chosen to inhabit silos, isolate ourselves through cellular systems defined by Group Think. It is against this culture, rife today, that Rose holds fast to “freedom of expression”. I jokingly asked Zeitz’s chief curator, Storm Janse van Rensburg, if Zeitz had installed a sound-proofed room for the “Karens” who would very likely be outraged by the show, but Van Rensburg’s answer was more understanding — that as a museum, as a retrospective, they would have to accept the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.

Van Rensburg is correct in stating that Rose’s solo show is “an emotionally-charged space” which, doubtless will spur outrage. But then, as writer, playwright and performance poet Lesego Rampolokeng presciently noted, “we don’t have a culture of criticism, only a culture of bitching”. Against this reactionary drive, Rose presents us with a world vision that is as personal as it is general, that compels us to absorb paradox and weather the raw rub of human difficulty. Rose speaks personally of “an ancestral bitch slap”, the realisation that cultural inheritance is in and of itself corrupted and corruptible. Of the more recent past, the 1990s — surely the South African art world’s first great defining moment — Rose notes that then “the art world was more progressive and messy”.

This is an apt description of Rose’s world, even today. The tension that underlies progression and evolution is, for her, invariably “messy”. This is as it should be, given that Rose is a wild card, a Fauvist, a beast, as exacting as she is perverse, as reassuring as she is enraging, as confident as she is profoundly wracked by doubt. It is for all these paradoxical reasons that I strongly recommend that you see Rose’s show. Titled Shooting Down Babylon, it is, as the title suggests, a Nietzschean tour de force, a rage against the machine, a denunciation — through autocritique — of all forms of idolatry, all unquestioned values and beliefs, all rear-guard certainties. Apart from the depth of the creative works on show, there is the added delight one experiences when entering a bling, sparkly, emerald-green corridor, which suggests a mirror ball, or Rose’s many-sided refracted personae. We enter worlds within worlds, the richly complex and protean world of Rose, which, for Kouoh, remains “unparalleled”.

Super Sometimes – Life In The UnderGround, 2012. Photo: Courtesy the artist and Dan Gunn, London

Super Sometimes – Life In The UnderGround, 2012. Photo: Courtesy the artist and Dan Gunn, London

But what I forgot, when I first drafted this essay — seduced as I was by the high drama the show generates — was a bracketed subtitle that applies to one specific work, The Art of War, a direct reference to Sun Tzu’s immortal military manual. Because, for all the seeming excessiveness and rage which the show conveyed — and the thrill which its uncensored delivery inspired — I had neglected to see its canny edge – the tricks and powers of dissimulation, the left-field takes on a problem, the varied ways in which Rose, after Sun Tzu, does battle.

As Sun Tzu notes, “In battle, there are not more than two methods of attack — the direct and the indirect; yet these two in combination give rise to an endless series of manoeuvres”. The variation in Rose’s delivery stems from her manipulation of direction and indirection — her “simulated disorder” that reveals her “discipline”, her “simulated fear” that reveals her “strength”. Shock is not enough for Rose, with it must come a seismic inspiration, for Rose wants none other than to change the ways in which we see and feel the world. Her significance in the eyes of Kouoh cannot be underestimated. And doubtless, in Zeitz Mocaa’s brief yet brilliant history, Rose’s solo show is its most provocative.

Sun Tzu sums up its daring-threat-power brilliantly: “Let your plans be dark and impenetrable as night, and when you move, fall like a thunderbolt.”

Shooting Down Babylon runs until 28 August 2022