Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu calling for peace in Katutura, Namibia in 1988. Photos: Rashid Lombard

Rashid Lombard is an OG (original gangster). A Grootman. A hard livings cat from a generation that loved and drank and danced and argued prodigiously and then stood up to the Man with the sort of fearless insouciance and fight rare in this age of superficial social media “politics” and “activism”.

Short, bespectacled and with a ponytail sticking out from under a pork-pie hat or a beret, Lombard, who turns 71 on 10 April, has been instantly recognisable in the activism and arts scene since the 1970s.

Back in the day, it was usually at the barricades, where he sought to document the brutality of apartheid with an unflinching lens, but also captured the humanity of the people that a violent and racist system sought not just to subjugate and turn into units of labour, but also to torture and murder.

Then he worked for media outlets like AFP and alternative newspapers like South and Grassroots and was published in books like South Africa: The Cordoned Heart (1986). During that period he also contributed to group exhibitions at the University of Zimbabwe in 1983 and the Staffrider exhibitions of 1984 and 1985.

More recently, after founding the Cape Town International Jazz Festival in 2000, it’s been usual to see Lombard at some function or gig, hopping animatedly from foot to foot while storytelling to a clutch of enthralled listeners and expertly managing not to spill a drop of wine in the bargain.

Hip-hop group Prophets of Da City with Nelson Mandela.

Hip-hop group Prophets of Da City with Nelson Mandela.

And the brother, who was born in Gqeberha (then Port Elizabeth) before moving to Cape Town with his family when he was 11, has stories to share: like the only time he “froze” on the job, when he rocked up to a protest in Cape Town during the ’80s and saw one of his sons on the frontline … or how he finally managed to get the legendary saxophonist Wayne Shorter to play in Cape Town.

With the recent induction of the Rashid Lombard Archive at the University of the Western Cape (UWC), I interviewed the photographer over email.

Niren Tolsi: The archives in South Africa — from national libraries and archives to those at some newspaper companies — exist in a state of crisis. Why do you think this is so?

Rashid Lombard: Well, my thought is that they have not been seen as economically relevant or viable; rather often being seen as burdensome. It’s a narrative we intend to play a significant role in assisting to change. The project that UWC and [my company] have embarked on is focused on the digitisation of heritage resources.

Heritage resources are and will be lost unless a concerted effort is made to house and digitise [them]. Without digitisation, the effect of heritage resource loss is not felt only by a family and the nation, but more specifically by numerous sectors as diverse as education, exhibitions, tourism, libraries and the numerous [people with] specialised skills who populate these sectors.

By digitising archives, and creating a repository for the resultant digital masters, we enable worldwide access and usage and also enable future economic return to the heritage resource owners.

A lot of people are looking to me and my company to see what we are doing in this regard of digitising our archive. This issue of digitisation is currently widely discussed by photographers and the estates of photographers. We are working with UWC to bring about a much better solution than is currently available and, for want of a better phrase, we are the guinea pigs, finding and cutting the future path.

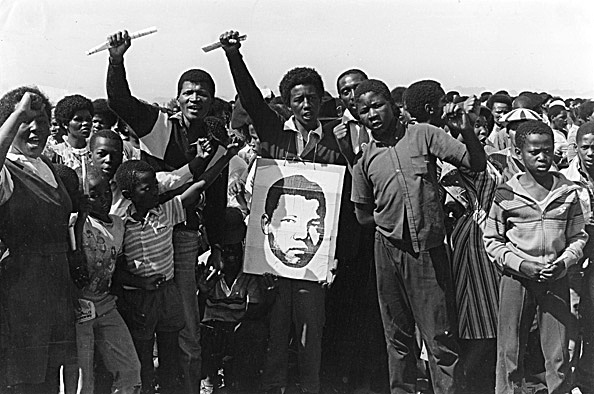

Students in Gugulethu calling for the release of Nelson Mandela in 1987.

Students in Gugulethu calling for the release of Nelson Mandela in 1987.

Lenin’s enduring question follows: What is to be done?

A huge amount of work, dedication, focus and commitment on the part of many with sensibility and sensitivity. Something built to last and not to break. As the work is still to be done, a thing of the future, I am reluctant to be specific presently.

Expanding on Lenin’s question though, what can be said about what is to be done is:

● Digitising the Rashid Lombard archive (a huge effort);

● Putting in place with UWC the plan to attract further heritage resources for digitisation to UWC’s repository;

● Lobbying the department of sports, arts and culture to complete and implement its digitisation of heritage resources policy — it’s been a work in progress since 2008 and is currently being completed — it’s a key road map for the country; and

● Raising funds for the project from institutions, government and the private sector.

The Rashid Lombard Collection appears to be just the starting point for the UWC-based archive. In an ideal world, what are your plans for it — especially in relation to your photographer comrades?

The project will create a globally relevant heritage resource and digital master archive, with the Rashid Lombard Archive as the starting point. Our plan is to set up a state of the art, world-class heritage resource and digital masters precinct from which the project will operate and which will offer opportunities for other heritage resource owners, especially other photographers, to locate their archives with the project at UWC.

In the meantime, until the precinct has been completed, my team and I have much work to do. The focus over the next three years will be on digitising my archive using international best practice, thus paving the way for my comrades to do the same.

So far, what we have planned and budgeted has the necessary funding from UWC and the state. The commitments are real [and] will enable the project to get underway. There will be an announcement about other role players soon.

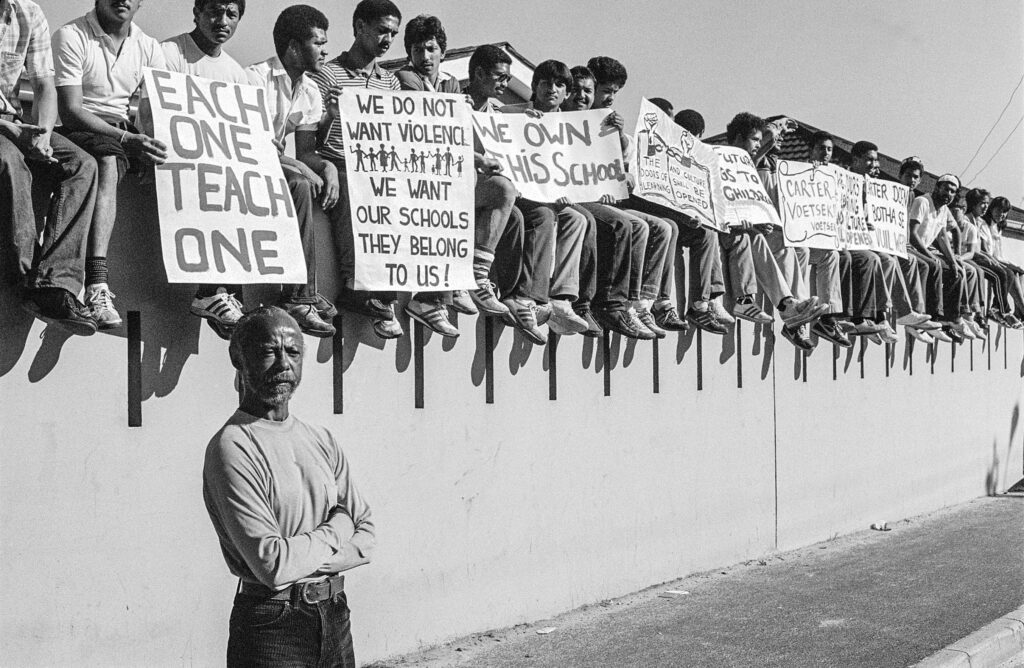

Writer and activist James Matthews with Alexander Sinton High School students protesting in 1985.

Writer and activist James Matthews with Alexander Sinton High School students protesting in 1985.

Why is preserving the archive so essential — especially in a country like South Africa which has its very specific and idiosyncratic sociopolitical history, especially in terms of pre- and post-apartheid eras?

Our archives tell our story in a language of our own; a language that is not the conquerors’ language — if we don’t tell our story, especially to the children and those to come, it will be told by others and our historical narrative will lose its truth. This will leave our children indelibly disconnected — a great tragedy that must be circumvented. That is why it is essential to preserve archives.

Photographic images of what happened are moments in time, frozen and fleeting. Capturing the good, the bad and the very ugly are the hallmarks of the language I use [especially in the 1980s]. This does not “fit in”, nor does it have to, for it is the very language of the oppressed.

Race alone does not ensure your photography uses a particular language. Photographic language depends on the political and social identity of the white or foreign photographer, or black photographer, for that matter, and whether that person identified with the oppressed. Our country has a history where [some of] those oppressed sided with the oppressors and where [some of] those from the oppressor sided with the oppressed — so things are not always clear cut.

Like most photographers from the ’80s, I imagine you must have rolls of film which start at a political rally or meeting and end at a music gig. What does that tell us about that time?

I term this period “the turbulent ’80s”. Every contact sheet of every roll of processed film tells many stories. It may start with images of activists challenging the police or a mass march or organisation’s meeting to discuss the next plan of action [and end at] a music concert.

There was this hive of participation by ordinary citizens involved in resistance for change. Music, especially a gig, was essential and central to life and survival. This also tells us that even in the doom and gloom of the heaviest days [during the states of emergency], we found small pleasures and humorous and magic moments [were woven] together whenever and wherever we could.

What effect did these small pleasures and magic moments have on you as a black person, an activist and a photographer, especially in the 1980s?

As a black person, as an activist and as a photographer … ? I was still one person living one life, and these small pleasures and magic moments were an outcome of that life; they were the effect of living it and were savoured and favoured as tasty morsels during a famine, received always in the company of others — very special and most often in private confines away from prying eyes and the impimpis of the time.

Artist Dumile Feni, New York, 1986.

Artist Dumile Feni, New York, 1986.

During the ’80s, with its states of emergency and fire and brimstone on the streets, what role did music, South African jazz especially, play in the lives of an oppressed people struggling not just against an unjust system, but to reclaim their humanity from that system too?

Many will tell you that whether listening, dancing or playing music, such moments were for the most part during those times, [firstly], personal retreats and spaces and, secondly, shared moments of joy and celebration …. of sadness and commiseration — like shared prayers sometimes. Food for the spirit and the soul that took the pain away.

You eschewed ‘objectivity’ as a photojournalist and once said that ‘you can only get a certain kind of image for news’ and that you often did not shoot for news, but rather, to ‘document what happens’. Please explain this conceptual (and political) impulse and philosophy?

An eye through the lens is an intensely subjective experience, regardless of the subject. Numerous other factors — light, aperture, lens, focus — come into play, no more so than the moment of taking the photograph. During those days, it was critical to capture what happened as such was hidden from the eyes of the world and the country. “What the eye does not see, the heart does not feel,” as has been said. I set out to capture as much of what happened as possible.

After photographing people at rallies, meetings, strikes and funerals, you would often follow up with recorded interviews at their homes. Why was that important in the ’80s?

To understand better the experience and the context of where, how and why the photography occurred.

Robertson student protest, 1985.

Robertson student protest, 1985.

Why is that important now?

It’s archival and part of our history — for us to tell, and not have it told for us by others.

What effect did these interviews have on your journalism and your politics?

Profound and intense … It spurred me on to capture more moments, to share and tell the story; to survive and live to tell the story.

In an era of fake news, there is a sense that South Africa is becoming increasingly ahistorical. Why do you think this is and what does this mean for society now and for our future?

In a sense there are many among the youth (and I mean under 25) who see our painful history as unnecessary baggage they don’t wish to be burdened with. Others among the youth, who through social media and the internet live in a borderless and very material world, have little interest in our heritage; nothing of substance it appears having been taught to them in their formative years.

For society and our future, our generation has an obligation, I would suggest, to make every effort to bring the relevance of historical past to their present, without burden and, instead, in a manner to imbue them with a sense of identity (which appears to be a challenge). Hence the relevance of this archival project — I do hope to encourage the youth to see this as a career path.

In 1986 you were awarded a Magnum Photos position in New York City. Was there anything different about how you approached photography during that time in comparison to how you were shooting in South Africa? Did that time away change your approach when you returned?

Yes indeed, from the day I landed in New York, I was in full-throttle learning mode in a real sense. When one learns, one improves and change seeps in quickly. That experience did not only change my approach, but I was also taught the “art of photography” and mainly the respect and relevance attached to photographers who lived in so-called “normal societies”.

In 1986 I was deployed to the US to study and research archiving; it was the analogue era. Peter Magubane got me the placement at Magnum Photos in New York under [the] guidance of the great Eli Reed. What’s very important during that time was the interaction with my mentors in the office: Philip Jones Griffiths, Bruce Davidson, Susan Meiselas and Rene Burri. This is where my respect for the importance of creating a living archive began.

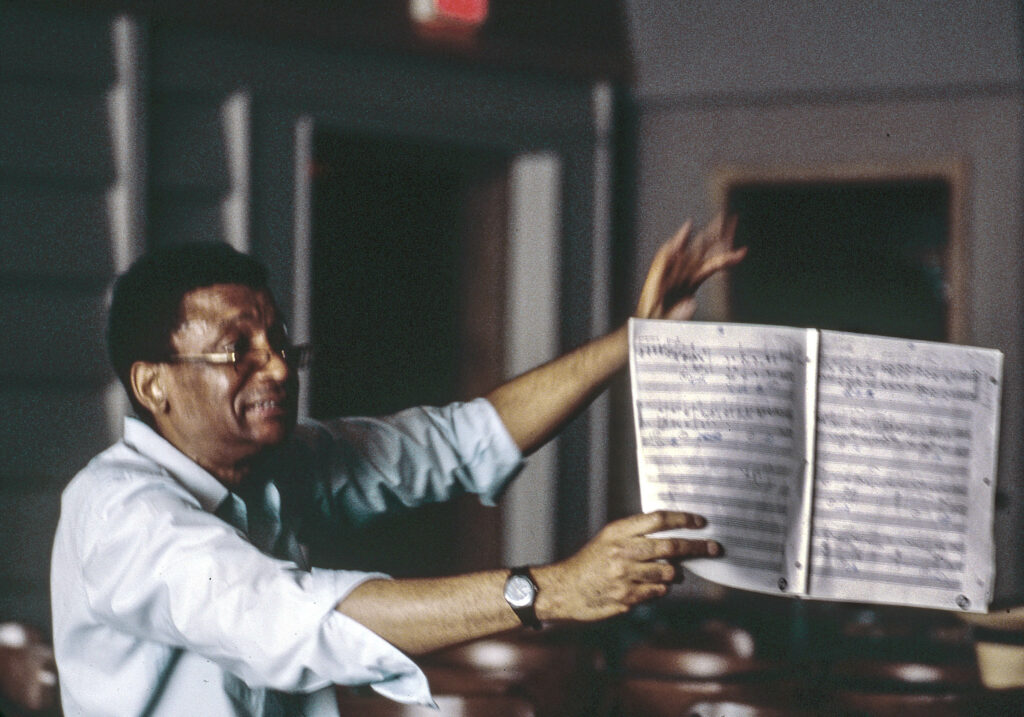

Abdullah Ibrahim, Boston, United States, 1986

Abdullah Ibrahim, Boston, United States, 1986

You met Ernest Cole there during that time. What was he, and that experience, like?

Special beyond! It was a real privilege to be with him. One of my missions when I was sent over to New York was to find Ernest Cole, author and photographer of House of Bondage. As like everyone does when they land in the States, you reached out to Abdullah Ibrahim and Sathima B Benjamin, who were my friends from Cape Town.

Abdullah said that Ernest will pop in … whether it’s in the week, a month or two months’ time. The wait was on! One night I received a call from Abdullah to say “Come over… Ernest is here”. This was three months into my stay and I rushed over filled with excitement. His first words to me were “Oh, thank God it’s not another student I’m meeting.” I was eager to just spend as much time with him and offered him anything he wanted — he was a simple man and only wanted “doughnuts and coffee” and that night is when our friendship began …

I believe you have more than 300 undeveloped rolls of film. Have you been surprised already by any of these that you may have finally had a look at?

I am sitting with a number of unprocessed rolls — while some may find this daunting, I do have quite a good memory of what’s on those rolls of film. But what’s exciting about those rolls is that I get to set up a dark room and start processing. The purpose of the state-of-the-art dark room is to wash, fix and rewash all the analogue celluloid archives and for any other unprocessed film that photographers have.