Char Carrie in Cycles Part 3. Credit: Duncan van der

Merwe.

The history of cinema begins with a bang. A 15-second loop of a man on a horse. A 50-second clip of a train that terrifies its audience. A 15-minute experimental short about an ill-conceived moon landing. The history of cinema has always been on the clock.

The French Riviera is no stranger to the movie scene and this week the best in the film business will gather to celebrate 75 years of Cannes and 150 years of film. But the Cannes Film Festival is not the first of its kind.

In November of 2018, Ster Kinekor’s V&A Nouveau hosted South Africa’s first 1-Minute Film Festival. The contestants ranged from wide-eyed beginners to industry professionals. The judges were writers, directors, local presenters and international actors. The task was simple: to tell the best 60-second story.

But simple is not always easy.

You could make your bed in 60 seconds, heat up a meal and if you really push yourself, perhaps you could even answer an email. But one really has to be special to make a 60-second film with coherent arcs, interesting visuals and a lasting narrative. It’s hard to do all three things at once.

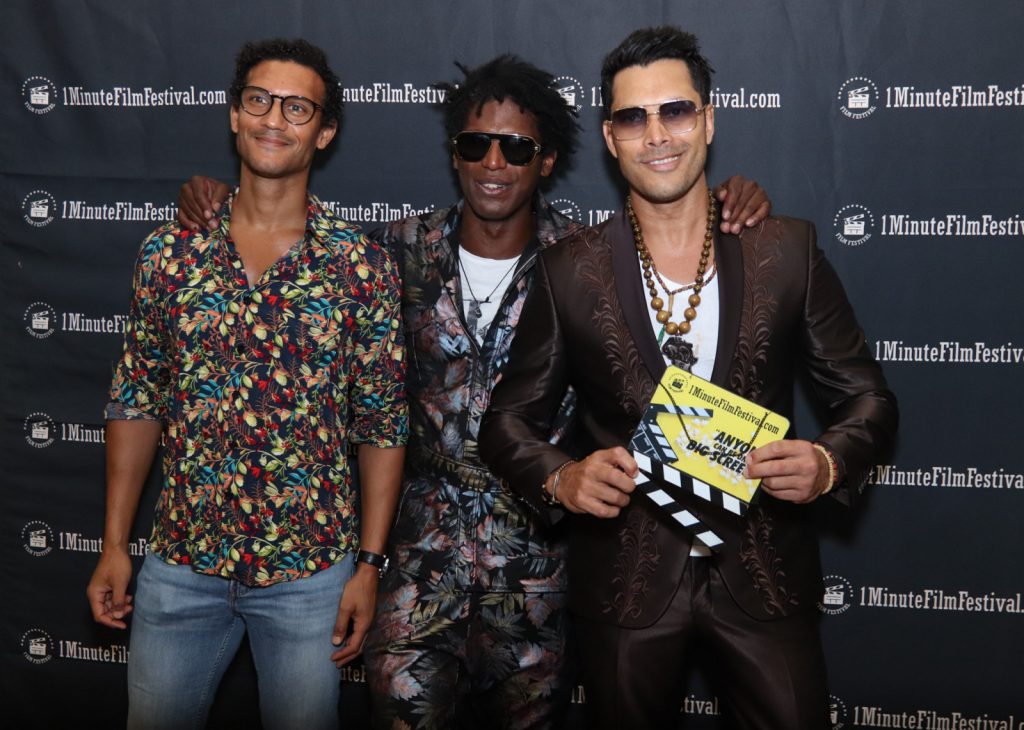

Brandon Wilson, producer VB Vexbhex and founder Thaamir Moerat at festival’s Cape Town edition. (Supplied by Thaamir Moerat.)

Brandon Wilson, producer VB Vexbhex and founder Thaamir Moerat at festival’s Cape Town edition. (Supplied by Thaamir Moerat.)

Modern cinema has become accustomed to taking its time. Films such as King Richard use everyman’s knowledge of public figures as the foundation for their stories. Euphoria captures the imagination because it spends an episode setting up each character. The Marvel Cinematic Universe uses entire trilogies for exposition. The teams behind one-minute films do not have the luxury of time.

Some short films use montages. Others use flashbacks. The best shorts ignore the fluff. The Ride, which placed first at the 2018 1-Minute Film Festival, is a real story told in real-time. It follows the conversation between an Uber driver and a passenger as they attempt to plan a pick-up in front of two metered-taxi drivers. It’s witty, well-presented and most importantly, short.

The actors use subtle actions to provide background information. A sigh tells us that the passenger has had a long day. An eye-roll tells us that one of the taxi drivers has seen this trick before. Every choice is treated with care. Everything is deliberate. Every second is a story.

One-minute films are a response to an increasingly economic world.

Duncan van der Merwe in his short film Cycles Part

2. Credit: Duncan van der Merwe.

Duncan van der Merwe in his short film Cycles Part

2. Credit: Duncan van der Merwe.

Infographics as social-justice arguments. TikToks as news. We are surrounded by neatly-packaged bits of information. When Twitter was launched, people felt that 140 characters were not enough to make a point. Now, it feels like an abundance of space.

Fifteen years ago, No Country for Old Men battled There Will be Blood for opening day tickets and The New York Times’ biggest competitor was The Washington Post. Now, everything is in competition with everything. The battle for the hearts and minds of viewers worldwide has become the battle for the eyes. News and memes compete for our attention on social media. Movies and reality TV shows compete for our attention on streaming platforms. Everything is accessible all the time. It is easy to claim that the rise of short films and the shortening of our collective attention span are synonymous with the fall of quality art. This assertion ignores the festival’s goal: democratisation.

Google “1-Minute Film Festival” and you’re taken to a relatively basic site. There are no flashy transitions, pretentious quotes or elitist takes. The festival’s philosophy is much the same. Screening everything taken from iPhone submissions to professional-grade art, it is a festival for everyone. In an over-saturated industry, competitions like this give people the opportunity to have their work seen and their voices heard. The 1-Minute Film Festival is not the end of cinema, it is the beginning of cinema’s new age.

Keaton du Plooy and the creative team behind Clown, Marlon Du Plooy’s award-winning short. (Supplied by Thaamir Moerat)

Keaton du Plooy and the creative team behind Clown, Marlon Du Plooy’s award-winning short. (Supplied by Thaamir Moerat)

The festival allows for creatives such as Keaton du Plooy, a 20-year-old editor to showcase his work; for artists like Duncan van der Merwe, an up-and-coming director, to enter multiple films and hone his craft in more than one genre. Du Plooy’s Clown explores the normalisation of South African gender-based violence by juxtaposing it with a children’s party. Van Der Merwe’s Cycles series interrogates the futility of everyday life. This new wave of filmmakers is not afraid to dig deeper.

Theatre did not stop novels. Film did not stop theatre. TV did not stop film. One-minute movies won’t stop long-form filmmaking. What they will do, and have done, is level a playing field that some thought would never change.

Thaamir Moerat, 1-1-Minute Film Festival‘s founder and managing director, is not afraid of this new wave of filmmakers. He wants them to collaborate, to take on many roles; he wants them to create, to experiment with dialogue, method and style. “I want them to change the art world,” says Moerat.

With the invention of the cell phone, anyone can make a movie. With the creation of the 1-Minute Film Festival, anyone’s movie can be seen. Cannes is historic, important even, but opportunities like the 1-Minute Film Festival are vital. They are proof that we live in an era where aspiring artists are able to create change, well-known artists are prompted to push boundaries, and all artists are forced to be more creative as time continues to be the modern world’s most valuable commodity.

Because when you are living in a media renaissance, it takes a big bang to catch the world’s attention.

The Cannes Film Festival runs from 17 to 25 May 2022. The 1-Minute Film Festival is back with three upcoming festivals in Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban, beginning in August.