As I enter the exhibition titled Names in Uphill Letters — A historiography of the newsmakers who tread(ed) South Africa’s soil, at the Workers Museum in Newtown, I encounter a photography lecturer, reflecting with a group of students on the picture frames by freelance photojournalist Jacob Mawela.

The museum itself has a chequered history starting out as a cleansing and sanitary compound on the eve of World War I to it transforming into an electrical workers compound in the Roaring Twenties. It was a storage facility in the 1980s, a library and now a formal museum in the new century.

To the new administrators’ credit this history is not hidden. For instance, the appalling conditions which the African workers were subjected to and the sheer discrimination are recorded and displayed in the courtyard where the workers used to take time off to exercise or rehearse skits and songs.

Former Drum staffer Mawela can’t hide his admiration for the late Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu. The clergyman is one of the subjects in the exhibition which took the photographer two decades to put together. “On the day I went, he and Mama Leah happened to be sick but he was still, in his affable way, gracious enough to welcome me for the photo session. He’s such a spontaneous person, I mean, I didn’t have to make him pose (unlike the other panellists), he just spontaneously started toyi-toying and I just clicked away,” says Mawela.

This is the third leg of the show; it has appeared in Benoni and recently in Tshwane at the Pretoria Art Museum. The photographer prefers to use anecdotes to explain his 50-odd A2 and A1-size monochromatic images documented on Ilford HP5 film, which are mainly portraits of famous (and infamous) South Africans.

In the time of the digital age, it says a lot about the traditionalist in Mawela, whose pictures are mostly in black and white.

He started to prepare the exhibition from as far back as the end of the 1990s when he was still with Drum: “I would photograph some of my subjects at least every fortnight and, if I was lucky, every week. But I slacked a bit after leaving the media industry due to disillusionment at the time. This was around 2002. But then Covid-19 came with the lockdown restrictions and I felt I needed to keep myself occupied.

“My spirits were also buoyed by an interview I did with the new manager at the Sun City resort. In the meantime my application for funding at the National Arts Council came through even though I only got a quarter of what I had applied for. This significantly reduced the footprint of my planned project. I could only exhibit 27 out of 108 prints. But the show had to go on for the launch in Benoni,” says the archivist.

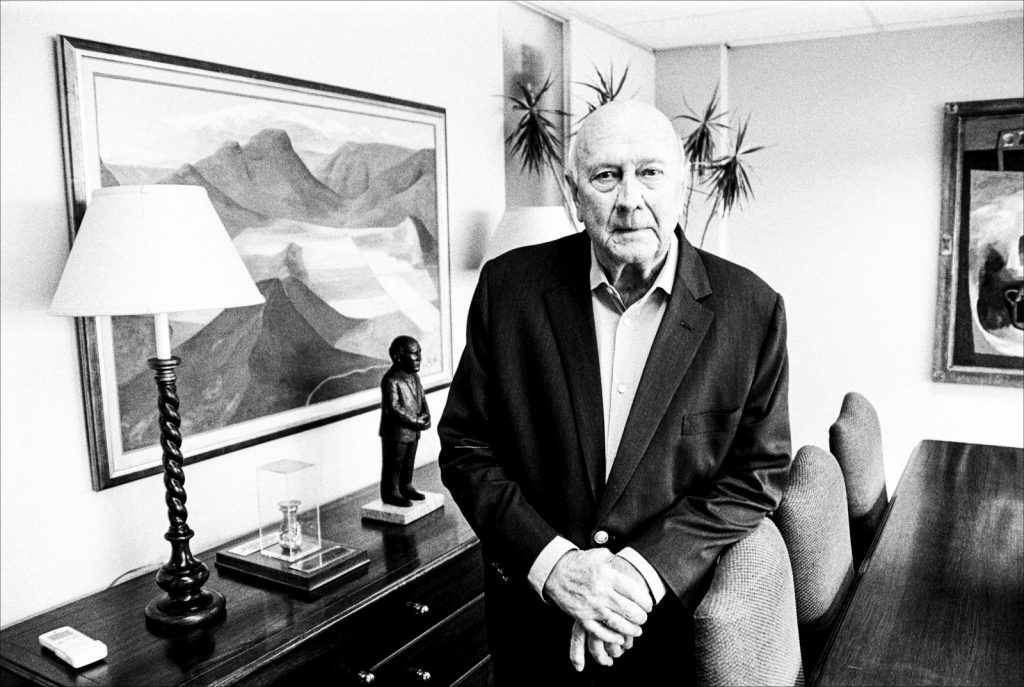

His subjects were always willing to pose for him. “It was easy. I did most of the initiating telephonically. It was the old way of checking them up in the directory. I remember tracking down the former president, FW de Klerk, through his foundation and getting a response from his PA on emails. From then onwards appointments were clinched. I flew to Cape Town to photograph him.

“Ironically, the greater the people in stature the humbler they were. For most of the subjects I didn’t have to wait too long for the confirmations,” he says.

One would say some of the choices for his subjects are controversial. The pictures span from De Klerk to George “Kortboy” Mpalweni, the leader of the Americans gang in Sophiatown.

But the photojournalist in him retorts: “Look, the subtitle of my exhibition is ‘historiography of the newsmakers.’ I’m a scholar/historian. My task is to record history and not to judge. De Klerk’s role in the ending of apartheid cannot be expunged. It was under his presidency that official apartheid was ended and the liberation movement unbanned which, in turn, set the country on a path to democracy.

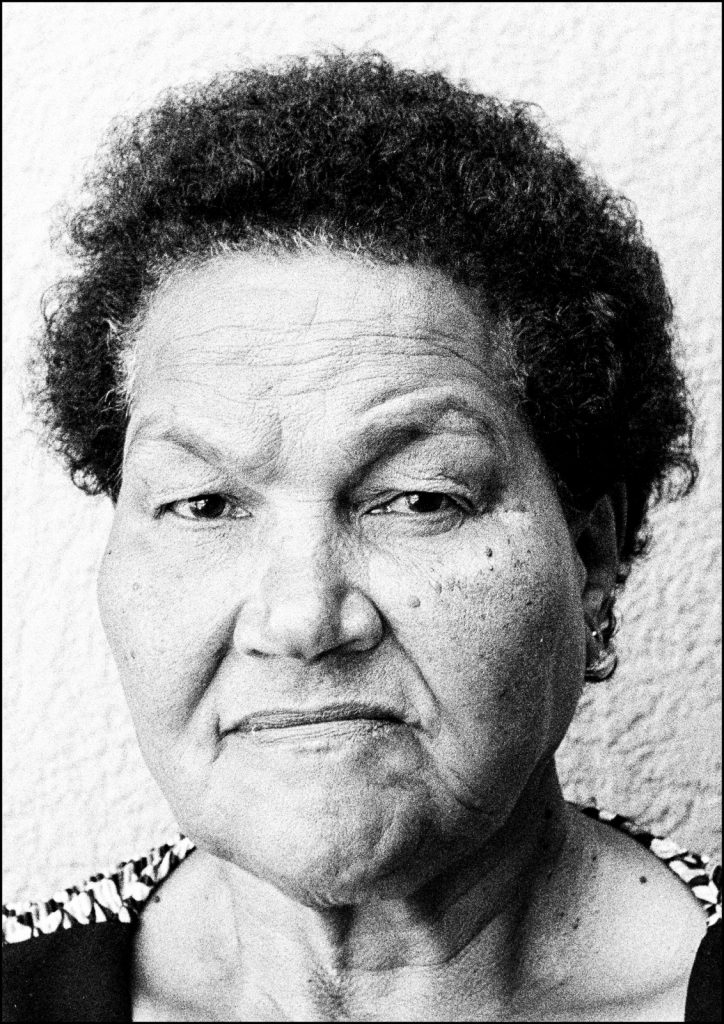

“In the same vein, one can argue that a figure like Kortboy is also controversial. I mean he was the leader of the Americans gang in Sophiatown, right? Should I have ignored him?”

I put it to him that it was almost expected that he would snap fellow photographers in the process, for instance, legendary photographer Alf Khumalo. Was it some sense of duty to the profession?

“No. I didn’t feel duty-bound. No other photographer has documented the Mandela family like Alf Khumalo — from the days the former president was still a lawyer in Johannesburg to the days he was released in the 1990s. Khumalo also photographed Winnie Mandela when she was banished in Brandfort in the Free State. In fact, he wrote several books on these experiences.

“He also documented the history of South Africa including events such as June 16. I picked him on merit solely for the role he played in documenting our country’s history. Khumalo was also personal friends with the Mandelas and Muhammad Ali, the greatest world boxing champion.”

In an ideal scenario , the anecdotes should have been included in the captions of the pictures on the wall, which are mainly portraits. But Mawela chooses to source the bios of most of his subjects from the news sources on the net.

Jurgen Schadeberg, the German-born South African photographer and artist who covered Sophiatown in the 1950s, including the Defiance Campaign of 1952, is captured by Mawela in his photography lab with his tools of the trade. Schadeberg seems out of focus looking at the viewer through a magnifying glass, spotting a wry smile.

Late jazz maestro Barney Rachabane, who hails from Pimville (Mawela’s hometown), stands next to a mannequin that is “listening” to the serenading melodies out of his horn.

Another interesting picture is that of the late Phillip Valentine Tobias, paleoanthropologist and professor emeritus at the University of the Witwatersrand. Tobias holds a hominid skull in a medical laboratory with a halo hovering above his head. He is not looking at the lens, his focus is on the exhibit in his hand. This no doubt places Tobias as an expert in his field of study. This is a deliberate positioning by the photographer.

Mawela is surprised that he got a space to exhibit at the Pretoria Art Museum recently. But if you take the angle of photography to mean “painting with light” then no eyebrows can be raised. Like an artist the photographer makes aesthetic choices to appeal to the viewer.

The exhibition is partly sponsored by the National Arts Council and the City of Johannesburg.

The Names in Uphill Letters exhibition is on at Workers’ Museum in Newtown, Johannesburg, until 29 July, Tuesdays to Sundays from 9am to 5pm. For special guided tours, make an appointment through the Workers Museum on 52 Rahima Moosa Street, Newtown.