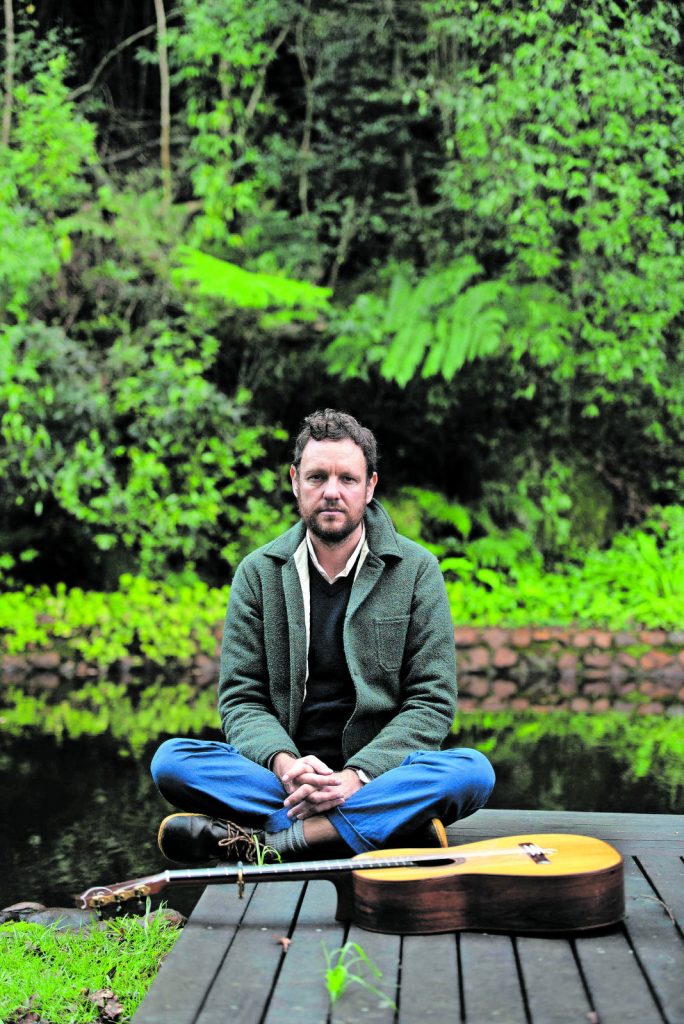

Merger: Guitarist Derek Gripper unwinds at a favourite spot near his home in Cape Town.

One fine day in Bamako, in 2016, Derek Gripper performed with Toumani Diabaté’s orchestra. This was not just any guest appearance in any distant city, it was the climax of an obsession. For years, the guitarist had immersed himself in the compositions of the Malian kora genius. His project was to devise a way to play Diabaté’s bewitchingly complex pieces — composed for a 21-string harp — on a six-string guitar.

He did it. On hearing Gripper’s Songlines-winning album Libraries on Fire, Diabaté was gobsmacked by the Capetonian’s ability to convincingly render his pieces using a hitherto ill-suited Western instrument.

Malian group Trio Da Kali perform at Carnegie Hall, New York, in 2016. From left, Lassana Diabaté on balafon, Derek Gripper on guitar and vocalist Hawa Kassé Mady Diabaté. Photos: David Harrison & Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images

Malian group Trio Da Kali perform at Carnegie Hall, New York, in 2016. From left, Lassana Diabaté on balafon, Derek Gripper on guitar and vocalist Hawa Kassé Mady Diabaté. Photos: David Harrison & Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images

Gripper’s secret, aside from his sorcerer’s ear and technical ingenuity as a player, was the act of transcription — creating and working from a score allowed him to reverse-engineer Diabaté’s music without the lifetime of tutelage and practice required to reach the same standard of recitation in the griot tradition.

Suddenly, the written tradition of Western classical music was plugged into the oral tradition of the griots; a transcultural wormhole had been opened. So, Diabaté invited Gripper to perform with his orchestra at the Acoustik Festival Bamako.

For Gripper, the show was exhilarating — and discombobulating.

“I did a solo set to an audience of about 500 people. Toumani was sitting on the side of the stage and in the front a line of the most illustrious griots. I get on stage and play a version of Kaira called Konkoba which, of course, the entire audience knows. Then they start clapping along.

“West African music is a little like French — you look at it on the page and you say it, but it’s wrong because the French know you leave out half the letters and it all sounds completely different.”

“So, in Bamako, they do that with clapping. You listen to the piece and think, ‘Okay, there it is.’ You tap your foot; it sounds right. But the Malian audience will go with a clave: a different clap that’s a beat-and-a-half out from what I expected. A clap in a completely different realm. If they hear Konkoba, they’re like, ‘Oh yeah, that’s the clap.’ And I’m, like, ‘Whoa, what is THIS?’ because I’ve received the piece from a studio recording where no one was clapping. It was wild. I had to speed up and slow down until I just lost them. And they all laughed and stopped, thank God. Then I could carry on doing my incorrect version.”

Except he wasn’t really incorrect, he was different. Gripper has been struck by the Malian appetite for musical strangeness and audacity; their pleasure at an outsider experimenting in their musical world.

Maestro: Derek Gripper spent years devising a way to play Toumani Diabaté’s kora pieces on a guitar. Photo: Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images

Maestro: Derek Gripper spent years devising a way to play Toumani Diabaté’s kora pieces on a guitar. Photo: Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images

It’s not an attitude he encounters on the classical performers’ circuit. “I remember going to Germany and playing some Bach prelude and having somebody come up to me and say, ‘Why did you leave out that bass note on the third page?’ That kind of ridiculous thing happens all the time. The orthodoxy that’s baked into our way of learning doesn’t exist in Bamako. If you come along and you’re clapping in a different place, they’ll say, ‘Oh, that’s an interesting place to clap.’ Or you’re playing the guitar with four fingers, not with two, they will say, ‘Wow, show me how to do that.’ Wrong doesn’t exist, it’s just other.”

He is used to being an oddity. “Of course, it’s just weird — this guy pitches up, doesn’t speak French, doesn’t speak Bambara, but suddenly plays like Toumani.”

Gripper hasn’t been back to Mali since because successive waves of violence and pandemic have isolated Bamako and its once-globetrotting community of musicians.

For a time, Covid-19 also stopped Gripper’s globetrotting. Before, he played Carnegie Hall, NPR’s Tiny Desk Concerts, Shakespeare’s Globe (alongside John Williams) and at dozens of music festivals across the world. Then he found himself locked up in his Cape Town house, the single parent of four teenagers. So, he set up a Zoom guitar workshop that quickly criss-crossed the world.

“Next thing, I was teaching three group sessions a day. There were guys in Switzerland and people in America and Australia and someone in China, giving us the lowdown on what was happening there, and a bunch of South Africans. That core group is still here. We’ve done 400 hours of Zoom over three years.”

Cut to the present, and barring a war or two, the world is breathing again. This month, Gripper’s troupe of teenagers is going on a hiking trip — while he embarks on a tour spanning England, Ireland, Canada and the US.

Gripper doesn’t do playlists for gigs anymore. “I’ve been training myself to arrive with nothing. I walk on stage with no idea about what I’m going to play,” he says. “I used to cheat — in the back of my mind I knew I was going to play this or that piece — but, as I’ve learned to trust that process and realise any plan I had is really going to be useless, it’s become quite a wonderful thing. I can react to the place I’m in and also resist my prejudices about that particular audience.”

That determinedly open stance — a readiness for the random twist, for the kairos or opportune moment — is the outcome of a long recovery from the strictures of his classical training. It didn’t help that the classical guitar has always been an awkward stepchild of the classical family, a transplanted folk instrument designed for taverns and farm lunch breaks, not concert halls and cathedrals.

On the other hand, “classical music” is itself a nebulous category, says Gripper. It has no period or ethnicity. So what defines it?

“The fantasy of ‘classical music’ boils down to the art of interpreting a text,” he says. “For example, in my first violin lesson, when I was seven, the teacher tied coloured threads onto the strings and then drew those colours above the notes. I had to play the green string when the green note happened, so I was learning to see something and respond with a sound. But in Bamako in 2016, I see this nine-year-old having his first kora lesson and there’s no piece of paper, of course. He’s shown what to do and he sits there and he does it.”

While Gripper’s music is sometimes described as a classical-griot fusion, he says that’s misleading.

“The collaboration is not a merging of classical music and griot music, it’s just a merging of two ways of engaging with a music, of two disciplines.”

He is alive to the issue of cultural appropriation but his work is arguably a textbook demonstration of how to absorb and contribute to another culture without appropriating it, in the sense of demeaning or exploiting it. Diabaté believes Gripper’s versions of his pieces are his own compositions, but Gripper insists they are Diabaté’s, and thus would never license the recordings for film soundtracks.

He has had a similar light-hearted argument with Madosini, the South African mouthbow composer.

“I have this painstaking transcription of one of the pieces on an album that I produced with her — just her playing solo about 10 years ago — and then worked out one of her pieces on guitar and played it back to her. She thought it was my composition and there was never a way to get her to think of it otherwise.”

But, in the contemporary pop music economy, an act of musical tribute is treated as either a crime or, in the case of legitimate cover versions, a pricy speculative investment.

“It’s thought of as theft because property is at the forefront in our minds. So, when we’re talking about profit, then we have a certain narrative. But when we’re talking about the conditions for the greatest level of creativity throughout a bunch of people, that would be the freedom to be able to do something without fear.

“That utopia of free creation still exists in West Africa and throughout most of Africa, for now,” says Gripper. “You can follow your body and take a song you’ve heard a million times, or part of it, and also sing about what’s happening now, and the music keeps on living, because the myth of the godlike creator, who has made something from nothing, doesn’t exist.”

Diabaté’s great 1987 recording Kaira was a case in point — a giant leap in this march of creative quotation. In making it, he gathered his heritage of ancient griot music into a personal artistic statement.

“Toumani, having listened to jazz, decides to record the kora as a solo instrument for the first time,” says Gripper. “He goes to London, plays in the studio for three hours and has those jams edited down into something else by Lucy Duran, who had studied kora for many years. So, it was highly mediated, and totally changed from its traditional mode, where someone’s playing these tunes with other musicians, while also talking and telling a story or a genealogy.”

The critical and commercial success of Kaira took Diabaté into the world music circuit, which was both a vibrant platform and something of a ghetto. Diabaté’s subsequent journey could equally have been in the classical world — which Gripper says is another kind of ghetto, albeit with larnier messaging. “It’s a little like the big gold frame around a Chagall; it’s a mediation which alters the trajectory of how we perceive, value and consume the artwork.”

In its defence, the classical circuit does get the technical stuff right, he says. “Because once you drop the ideas about what you should be doing and wearing and how you should be behaving, concert halls are pretty amazing. The amplification is incredible now, and you play this little guitar and you fill this huge space. Everyone’s trained over decades to be silent and listen, so you can hear a pin drop. It’s like a magnifying glass on this instrument.”

Gripper’s guitar was made two decades ago by the family of Hermann Hauser — the great German craftsman who built Andrés Segovia a guitar powerful enough to fill a concert hall.

“It’s two generations later but made from the same block of wood as Segovia’s. Once a year, he uses the same wood and makes one guitar. I somehow happened to get one.”

In his early twenties, long before discovering Malian music, Gripper immersed himself in Segovia and the Spanish tradition. After that, he teamed up with his brother-in-law, the late Alex van Heerden, to explore the traditional sounds of the Cape: ghoema and vastrap. With Van Heerden’s accordion, Gripper played on the strange and fascinating Sagtevlei in 2003.

“Alex and I had been obsessed with making South African music. I suppose it comes out of an insecurity, of thinking our only value as musicians was our location. At some point, I was challenged on this and made to realise that there was more to the story of me and what I wanted to do than, ‘I’m from South Africa.’

“But there was still a need to escape the stultifying faux-poshness of classical guitar, and the musty Spanish nationalism of Segovia. We needed to ask, ‘Hey, what was this instrument before we started getting all these delusions of grandeur?’

“That was also the moment when, after about a decade of listening to Toumani’s Kaira, I started thinking of him as a composer rather than the Keith Jarrett of Mali. And I thought, ‘Well, if these are compositions, then I could play them. I just have to write them down first.’”

And that was the opportune moment.