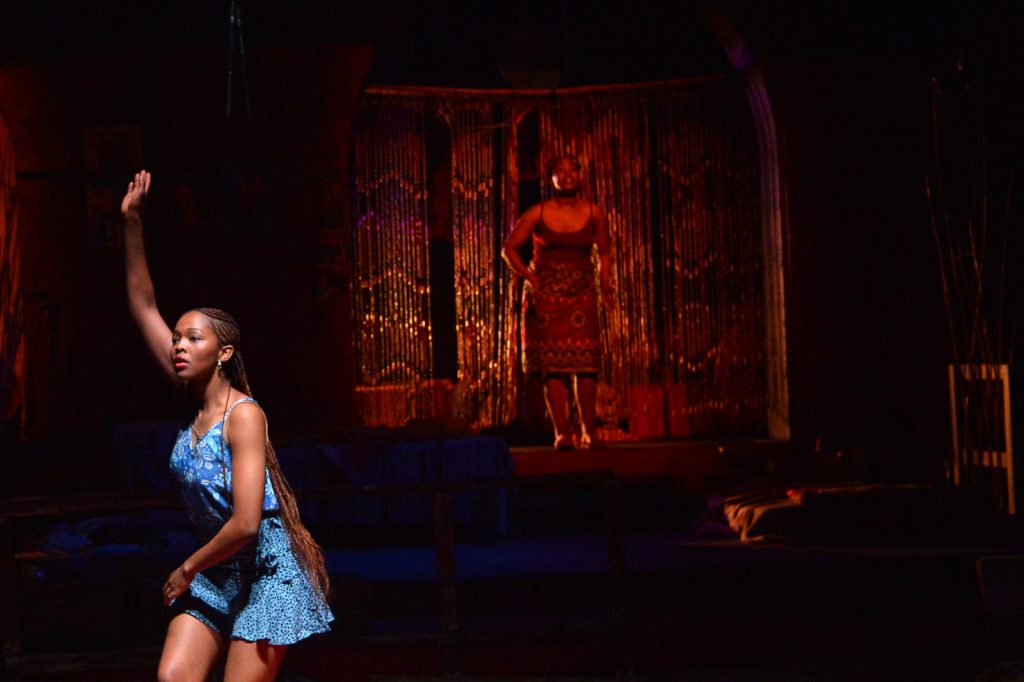

Taking no prisoners: Hlengiwe Lushaba Madlala and Vaughan Lucas Callaway in a heated moment in Ruined. Image: Lungelo Mbulwana

The Market Theatre in Johannesburg celebrated this year’s Women’s Month with a second play in the line-up by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Lynn Nottage, Ruined. The play, which saw its South African premier last season, had a local cast and director.

Nottage started penning her first play at the age of eight. She went to New York’s High School of Music and Art, in Harlem, New York. After her undergraduate studies at Brown University, she earned an MFA in playwriting from Yale University.

Enough is enough: Shoki Mmola and Fulu Mugovhani protesting injustice. Image: Lungelo Mbulwana

Enough is enough: Shoki Mmola and Fulu Mugovhani protesting injustice. Image: Lungelo Mbulwana

Ruined is the product of a sojourn in Africa, where she interviewed girls and women in war-torn countries. The interviewees were “girls and women who themselves were, and continue to be, the battleground upon which war is fought”, as the theatre’s publicity aptly states.

The local cast included 2022 South African Film & Television Award-winning actress Shoki Mmola, who made her name in local television drama series Skeem Saam. In Ruined, she plays Salima, a troubled peasant girl who is abducted by rebels in the Democratic Republic of the Congo during the civil war. Her captors use her as their concubine before discarding her in the bush.

This involved sensitive storytelling by Mmola, who revealed the challenge of playing Salima in a recent Instagram post: “I also fear doing her injustice because this piece forces me to take a journey that boldly amplifies the shadows on our backs. All I ask for now, is an opportunity to access courage, and tell Salima’s story, with honesty and care,” she said.

Her husband in the play, a farmer-turned-soldier, is played by Tebogo Sebogodi, best known for his portrayal of Khabzela in The River. While her husband is out looking for a pot in which to cook their dinner, the rebels pounce on the unsuspecting Salima and her young child. In the process, her baby is killed, while she is “ruined”. This has lasting effects on her stability and she is never the same after being sexually violated. Meanwhile, her husband goes on a never-ending journey to find her.

At the start of the play, roving salesman Christian (Anele Situlweni) sets the scene of the Congo during the civil war while enjoying a Fanta at Mama Nadi’s Place: “Every 2km a boy with a Kalashnikov and pockets that need filling. Toll, tax, tariff. They invent reasons to lighten your load.”

Of course, here “lightening your load” means the opposite – adding more burdens to the heavy load.

The main character, Mama Nadi, is impeccably handled by Hlengiwe Lushaba Madlala (Tjovitjo, Gaz’ Lam, Intersections), who reveals what the drama represents: a sadness and a smile.

She is the unscrupulous brothel/bar owner who looks out for her own but sometimes shows a soft spot for the victims of the war. For instance, in the opening scene, she is convinced by the two-timing Christian to take two girls instead of one into her “safe” haven: “Are you deaf? No. Tst! I don’t need two more mouths to feed and pester me,” she says. But the sly salesman retorts: “Take both. Feed them as one …” Mama Nadi will later organise restorative surgery for another “ruined” girl in her stable, Sophie (Fulu Mugovhani).

Speaking truth to power: Fulu Mugovhani,Hlengiwe Lushaba Madlala and Molefi Monaise in combat mode.

Image: Lungelo Mbulwana

Speaking truth to power: Fulu Mugovhani,Hlengiwe Lushaba Madlala and Molefi Monaise in combat mode.

Image: Lungelo Mbulwana

The script works well at many levels and at others it hits you with a reality check about the colonial legacy in many post-independence countries on our continent. This is underlined by Mama Nadi in act one (scene 2) when she asks the Lebanese mineral merchant Mr Harari (Vaughn Lucas Callaway) to prospect the rich minerals in her possession: “I don’t want someone to turn up at my door and take my life from me. Not ever again. But how does a woman get a piece of land, without having to pick up a fucking gun?” she asks.

Ruined was directed by Clive Mathibe who directed the stage adaptation of Father Come Home, by the late literary giant Es’kia Mphahlele, as part of the centenary celebrations for the writer at the Market Theatre last year. Mathibe, who has also done television work, had this to say about his latest project: “I am thrilled and honoured to be telling this story with some notable collaborators in the design team as well as the impeccable cast.”

The play is relevant in the South African context, although technically this can’t be classified as a war-torn country. But it doesn’t have to be. The reality reveals a society divided along the lines of class, nationality and gender, among other social indicators. This makes many a potential force for change despondent because of the arduous struggles we have been through as a country, with not much to show for it – many are still left out in the cold.

Moving Target: Thapelo Sebogodi taking no chances in enemy territory. Image: Lungelo Mbulwana

Moving Target: Thapelo Sebogodi taking no chances in enemy territory. Image: Lungelo Mbulwana

If we go by the dominant narrative, we should be somewhere floating on the rainbow of a post-apartheid land by now but recent incidents of racism prove this is not so. Too many acts of bigotry happen too often and too close for comfort.

The struggle of the landless continues because few land redistribution targets have been met (even by the incumbents’ standards).

Likewise, women’s struggle for full emancipation still has a long way to go, despite legal reforms here and there. The systematic and systemic patriarchy persists although more households are headed by women, for example. This is also reflected by the income disparities between the genders.

It will take powerful institutions, such as organised religion, a powerful civil society and the state (understood in its full sense of having multiple arms, including education) to intervene in changing the mindset.

Meanwhile, plays like Ruined, located as they are in the realm of ideas, can only have meaning if we take collective action to reflect on their implications for future generations. Hopefully, our story as a continent will end like the play where love conquers all, in spite of the frailties of some sections of humanity. And, as one of the songs in Sophie’s repertoire goes: “Cuz/ You come here to forget/ You say drive away all regret/ And dance like it’s the ending/ The ending of the war…”

Dance of Defiance: Sami Maseko gyrates to the beat of the war drum in Ruined. Image: Lungelo Mbulwana

Dance of Defiance: Sami Maseko gyrates to the beat of the war drum in Ruined. Image: Lungelo Mbulwana

For more information, visit the theatre’s website www.markettheatre.co.za