William Kentridge in his studio in Joburg.(Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Commerce is central to the broader experience of William Kentridge’s London takeover, which includes two solo exhibitions, the most notable being a scintillating retrospective at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA).

Exiting the last of the 13 rooms in Burlington House devoted to the 67-year-old Johannesburg artist’s drawings, prints, paintings, sculptures, tapestries, films and mechanical theatres, made since the mid-1980s, one enters a large gift store.

It is dizzying, all the goodies being offered. They include familiar standards such as postcards, posters, tote bags and books from the growing library devoted to Houghton’s most famous resident after Nelson Mandela. Among them is a new RA tome titled — like the exhibition —after the artist. Its author is Stephen Clingman, a US-based literary scholar born in Johannesburg.

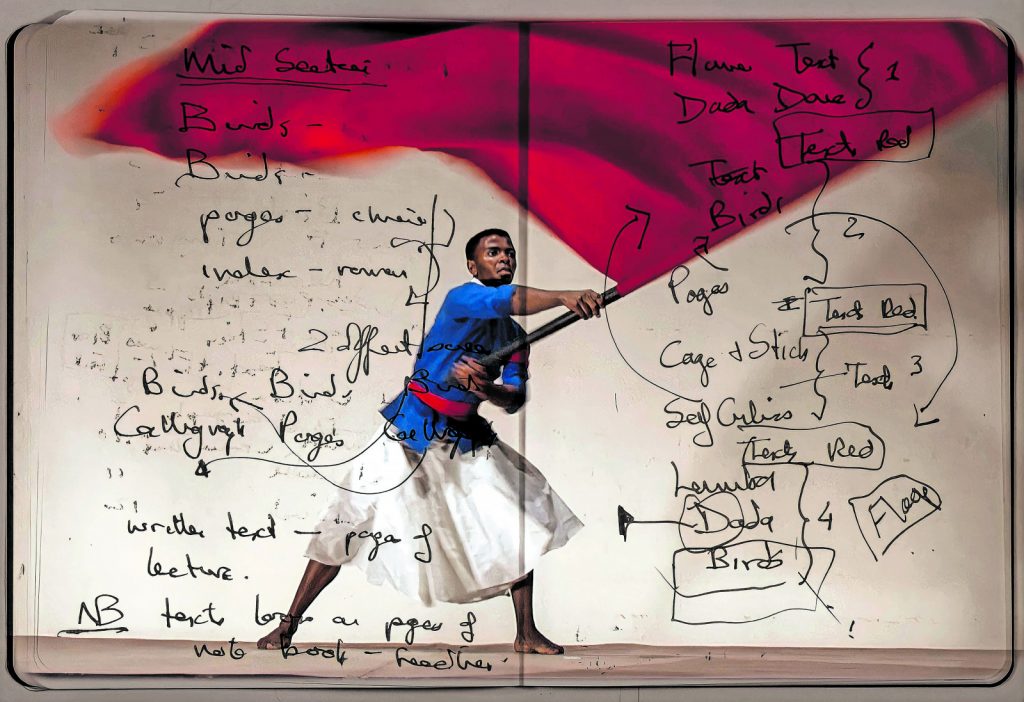

“The key question about Kentridge’s art is not what does it mean but what does it do,” argues Clingman. “The ‘doing’ is a question of technique and process which becomes nothing less than the totality of the work itself.”

For those who prefer drawing to reading, there is a natty box of charcoal sticks labelled “William Kentridge’s Favourite Drawing Charcoal Box” (R420). The sticks were handmade for the RA exhibition in Mpumalanga by Simon Attwood.

Other knick-knacks include pencils, bottles of black ink, notebooks, moka coffee pots, black swivel lamps and a range of beaded necklaces (R2 000 to R10 500) produced in collaboration with Marigold, a beadwork co-operative in Bulawayo.

For the most part, the keepsakes playfully celebrate the materials, colours and props informing Kentridge’s old-world aesthetic. However, one item, a bespoke unisex fragrance named “&”, explicitly evokes the lush suburban space on the lower slopes of Houghton Ridge where the artist lives and works.

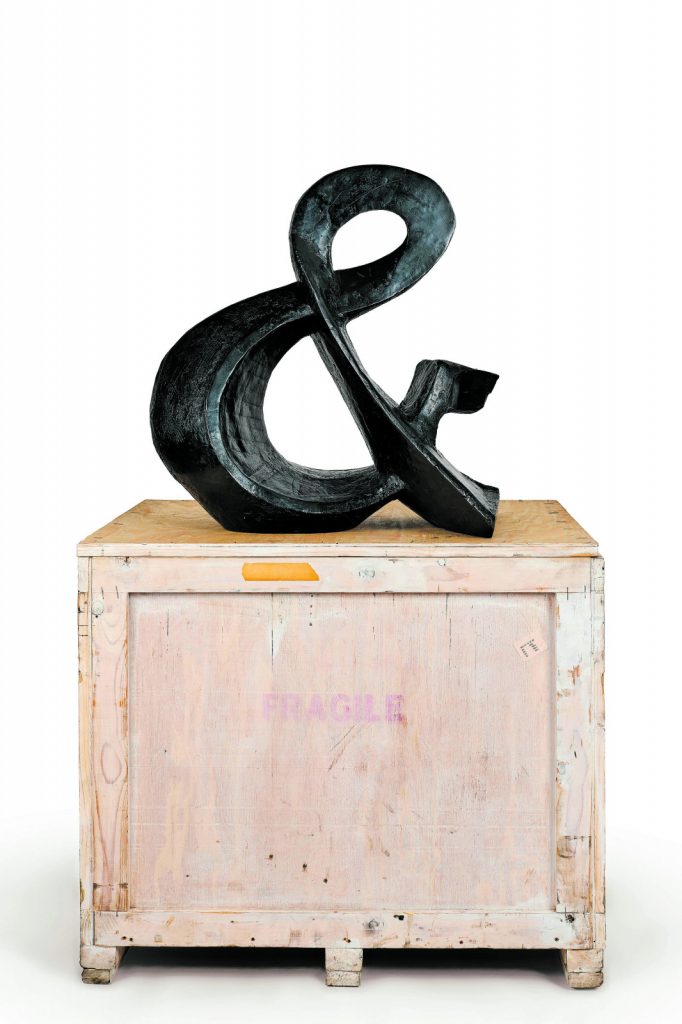

A William Kentridge sculpture

A William Kentridge sculptureA petite sign in the gift store explains the rationale for its five notes, which include bergamot, black pepper and cassis: “It is the comforting dustiness of old books, irises drawn in charcoal, the fountain gurgling outside the studio door, a crisply pressed white cotton shirt and wooden plan chests, laden with prints and drawings.” Sexy.

The 100ml fragrance was made in collaboration with Floris London, the oldest family-run perfumer in Britain. It is priced at R6 250. This is substantially less than the R5-million to R6-million Joburg auction house Aspire anticipates a buyer will stump up for Kentridge’s favourite logogram when a 2017 sculpture depicting an ampersand goes on sale on 30 November.

Kentridge’s openness to translating his idiosyncratic aesthetic — a scavenged miscellany of historical English, French, German and Russian art influences — into merchandise is nothing new. He has in the past produced flipbooks, stereoscopes, puzzles and paper sculptures for his multitude of museum appearances. Designing gift-store trinkets and museum editions of his work has become an occupational hazard for Kentridge in the decades since musician and art collector David Bowie hailed him as the “white-heat high point” of the

1995 Johannesburg Biennale.

In May, I watched two craftsmen labour over models depicting a spiky cat, moka pot and two figures with megaphone heads. Kentridge later appraised the models, deciding which would work for his gallery show and which as museum editions. It was one of many labours that kept him busy that day.

“It is a bit insane,” apologised Kentridge, whose star remains firmly in the ascendancy.

The latest feather in his cap is the RA show. A storied institution founded in 1768, the RA is well known for its blockbuster shows. Kentridge’s exhibition follows on similar large-scale solos by Anish Kapoor (2009), Anselm Kiefer (2014) and Ai Weiwei (2015).

Realising the exhibition was not without problems. The pandemic battered the RA. Programming was upended. There have also been grumblings of budgetary constraints. You wouldn’t guess this encountering Sabine Theunissen’s magical exhibition design, which uses raw timber for plinths and seating, and brightly coloured carpets to block off discrete spaces within the gallery.

A bronze depicting the artist’s favourite logogram, 2017

A bronze depicting the artist’s favourite logogram, 2017Adrian Locke, the RA’s chief curator, explained his biggest challenge was conceptual, not financial. London has seen a lot of heavy-duty Kentridge traffic.

In 2018, the artist premiered The Head and the Load, a large-scale theatrical performance about Africa’s central role in World War I, at the Tate Modern. Two years earlier, six of his large film and sculpture installations were gathered at the Whitechapel Gallery.

Locke’s solution to Kentridge’s hyper visibility has been to focus on drawing. “William is an absolutely brilliant draughtsman, working in charcoal and Indian ink in this effortless manner,” says Locke. “He himself says everything starts with drawing. It is through the drawing that he really expresses himself.”

The exhibition opens with two rooms of drawings before yielding to works in other media. The first room of early drawings includes The Conservationists’ Ball (1985), a surrealistic triptych depicting the leisured white citizenry of an Europeanised African city roiled by traffic jams and animal rights. It remains a trenchant critique of bourgeois manners.

A second room of 16 drawings devoted to Kentridge’s filmic alter ego, industrialist Soho Eckstein, features a salon-style hang. One work, though, a process drawing from Other Faces (2011), from the artist’s acclaimed Drawings for Projection series (1989-present), is presented by itself on an adjacent wall.

It shows Soho — who strongly resembles Kentridge — attending a frail, bedridden woman. The work is an elegiac study of family and devotion. It draws substantially from the artist’s biography. Kentridge’s mother, lawyer Felicia Kentridge, was paralysed in later life by a degenerative disease. She died in 2015.

In late September, his father, lawyer Sir Sydney Kentridge, was given a special preview of the RA show. He was wheeled through rooms installed with his son’s myriad work, which in the RA includes Stephens Tapestry Studio-produced woven textiles portraying silhouetted figures overlaid onto antique maps.

Carte Hypsométrique de l’Empire Russe, 2022, William Kentridge’s hand-woven mohair tapestry.

Carte Hypsométrique de l’Empire Russe, 2022, William Kentridge’s hand-woven mohair tapestry.

Sydney, who turned 100 on 5 November, frequently used to ask dealer Linda Givon about the viability of his son’s career. “He was very surprised when William started earning money [from art],” Givon told me in 2007. “Yes, but how long will this last? Do you think William will carry on selling his work?”

The work on view in the RA presents an emphatic answer: “Yes”.

To sell is to live, especially in South Africa, where the art world is primarily commercial. Kentridge is well aware of this. He does not view himself as above the transactional economy in which his work exists.

“The society we live in is so much determined by commerce, with buying and selling, that to pretend I was indifferent to it would be absolutely wrong,” he once told me.

Kentridge’s very first exhibition was a selling show. Held in 1979 at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg, it featured drawings and about 30 monoprints, the latter priced at R60 each or R90 if framed.

All Kentridge’s current top auction prices postdate the 2011 sale of his drawing Preparing the Flute (2005) for R4-million at a New York auction. By then he was a major fixture on the international art scene, with a solid museum track record.

Kentridge received his first solo museum exhibition in San Diego in 1998. The artist has since had 186 solo exhibitions in museums globally. They include William Kentridge: In Praise of Shadows, a newly opened headline survey of 130 works at The Broad, a ritzy contemporary art museum in Los Angeles.

A recent art market report by London market research outfit ArtTactic found of Kentridge’s more than 700 exhibitions since 1979, the vast majority (roughly 85%) have been staged in non-commercial “institutional” settings. Although nothing is for sale, museum shows tend to operate as authorising stamps, especially for collectors and speculators. Kentridge, though, is an anomaly.

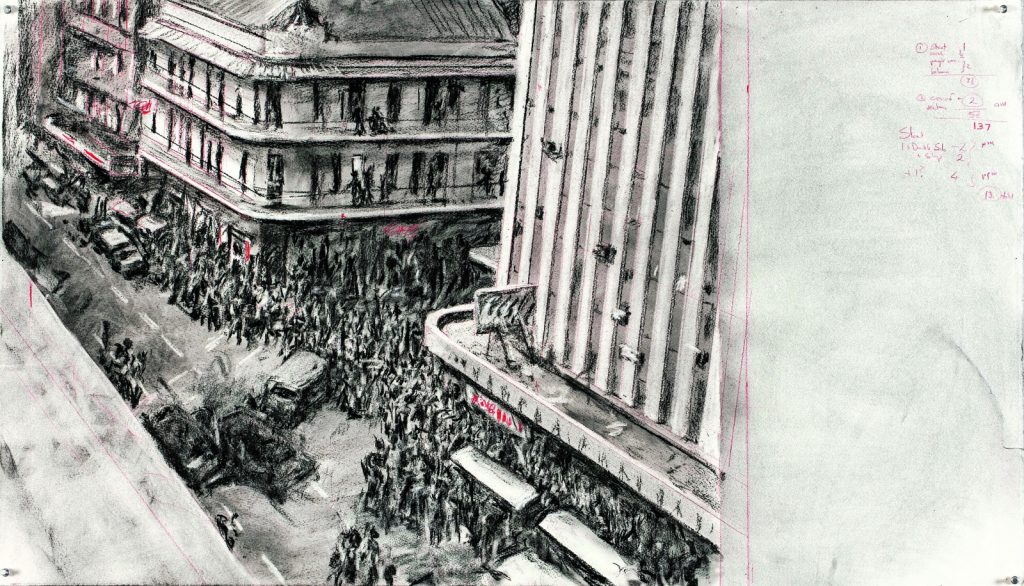

William Kentridge’s drawing for Other Faces, 2011, done in charcoal and coloured pencil. (Courtesy of William Kentridge)

William Kentridge’s drawing for Other Faces, 2011, done in charcoal and coloured pencil. (Courtesy of William Kentridge)

“Kentridge’s auction market remains of a modest size compared to other artists of similar standing,” notes ArtTactic in its September report on the artist.

It is painter Marlene Dumas — not Kentridge — who holds the dubious honour of being the most expensive living South African artist. Her 1995 painting of a group of sex workers, The Visitor, fetched R50-million at a 2008 auction in London. Kentridge’s highest-priced work at auction is the drawing Large Typewriters (2003), which sold at Bonhams, London, last year for R15-million. (The quoted prices are based on the rand exchange rate at the time of sale and are not inflation adjusted.)

Earlier this year, ArtTactic revealed Dumas is the highest-earning African artist. Work by the Amsterdam-based painter achieved R721-million from 91 lots sold at auction between 2016 and last year. Her nearest rival is painter Irma Stern, not Kentridge, who only placed ninth in the ranking with earnings of R231-million from 396 lots sold.

Kentridge’s wonky auction performance is partly attributable to the scarcity of his large sculptures in the secondary market, as well as a collector bias towards painting rather than drawing. “But could this year be a tipping point?” ask ArtTactic, pointing to the institutional shows in London and Los Angeles as prompts for buyers to revalue the importance of the artist. The art market is notoriously fickle and hard to read.

A video still from Notes Towards a Model Opera 2015. (Courtesy of William Kentridge)

A video still from Notes Towards a Model Opera 2015. (Courtesy of William Kentridge)

Last month, a 1985 Kentridge drawing depicting Bolshevik bigwigs Alexei Rykov and Nikolai Bukharin achieved an indifferent price of R672 212 at a London auction. He priced his drawing at R600 in 1985.

Kentridge’s interest in the utopian fancies and political failures of Soviet-era Russia also inform his current solo exhibition at Goodman Gallery in London. The exhibition takes its title from a new film installation, Oh To Believe in Another World. Inspired by composer Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10 (1953), the film features a cast of performers wearing masks depicting early Soviet luminaries.

“What is to be done,” reads a statement without a question mark on one screen while, on another two, Lenin shuffles inside a paper costume and wags a big finger. The colonnaded hall in which the action takes place is fictional. Kentridge and his team built a scale model of the setting in his studio, and also filmed and edited it there.

Available in an edition of seven, the film is priced at R10-million per edition. Three editions of this film currently have sales pending.

A tipping point? Definitely, maybe.

William Kentridge runs at Royal Academy, London until 11 December; William Kentridge: In Praise of Shadows runs at The Broad, LA, until 9 April 2023.