‘Uncontrollable Calm’ appears as part of of Tavares Strachan’s exhibition ‘The Return’, which is on at the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg until 7 October. Photos: All images courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

On the opening night of his first solo exhibition on the African continent, the Bahamas-born, New York-based artist Tavares Strachan wore a black astronaut jumpsuit. Strachan, who rocketed to art-world visibility in 2020, didn’t seem out of place in fashion-conscious Rosebank.

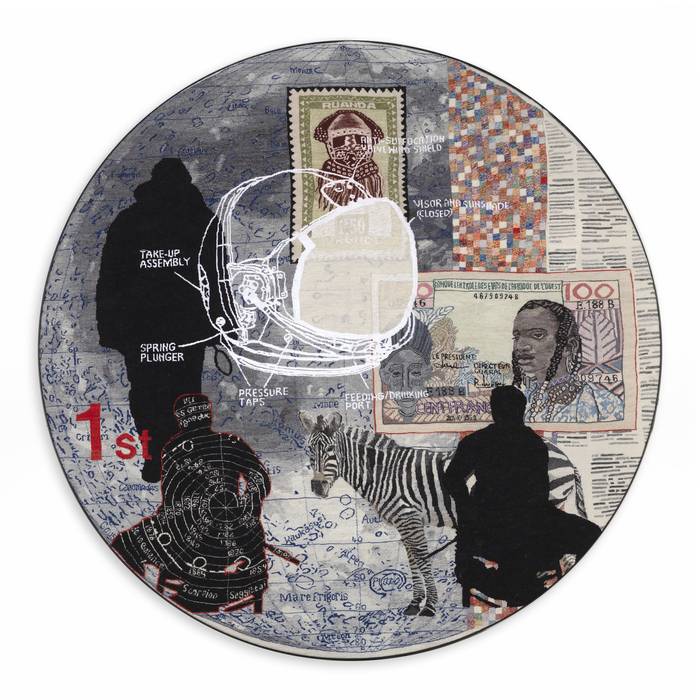

But, much in the way that the pince-nez worn by Johannesburg artist William Kentridge signifies, so Strachan’s getup directly connected with his Goodman Gallery debut. The Return, as his exhibition is titled, features clay sculptures, circular tapestries and dazzling light-box paintings that substantially reference celestial bodies and space travel.

Strachan is an admirer of Robert Henry Lawrence Jr, the first African American chosen by Nasa to be an astronaut. In 2018, after five years of hustle, Strachan launched a 24-carat gold bust of Lawrence into orbit using a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

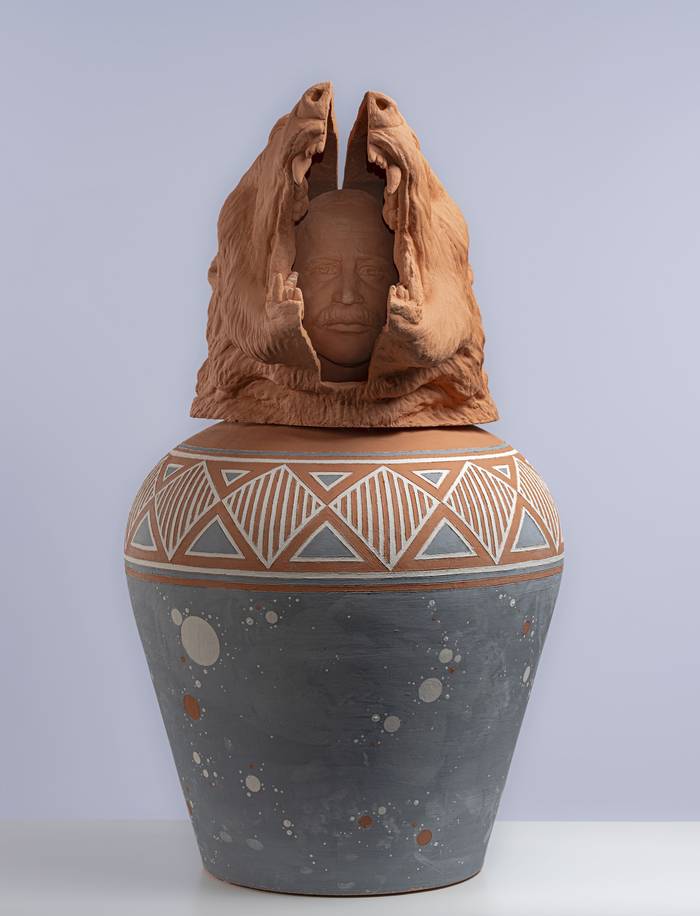

Strachan’s devotion to Lawrence endures. The Return includes a large clay urn decorated with luminescent stars and geometric patterns, atop of which appears a likeness of Lawrence inside a space helmet, also modelled from clay.

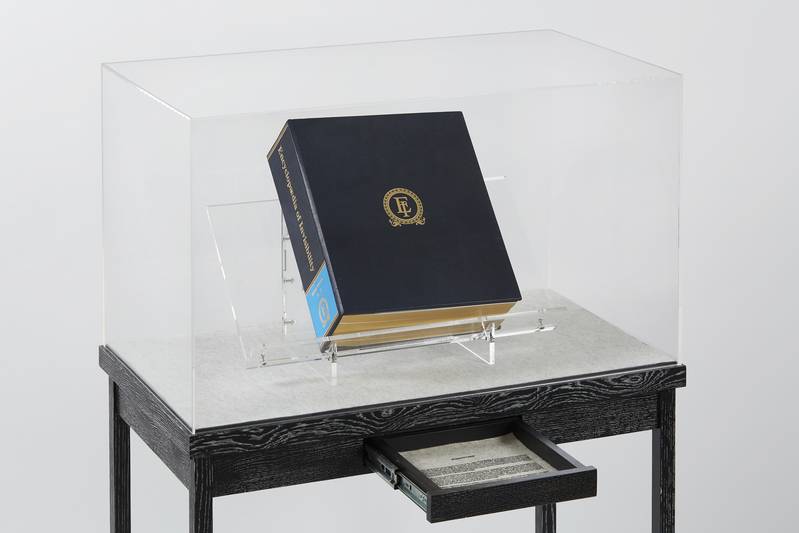

Lawrence’s biography — born in 1935, US Air Force pilot at the age of 21, chemistry doctorate, died tragically in 1967 in a test flight before entering space — is recapped in another object on view in the gallery. The Encyclopaedia of Invisibility (2018) is a 2 416-page book containing over 15 000 entries describing people, places, objects, concepts, artworks and scientific phenomena that, to quote the foreword, “are hard to see and difficult to ascertain”.

Tavares Strachan’s ‘Afronaut (Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. with Space

Tavares Strachan’s ‘Afronaut (Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. with Space

Helmet). All images courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

‘Afronaut (Matthew Henson with Polar Bear)’. All images courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

‘Afronaut (Matthew Henson with Polar Bear)’. All images courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

Strachan’s book has been summarised as a repository of overlooked and neglected black history. It is far more ambitious than that. Its entries span the globe and range across time. There are descriptions of Abell 2744, a distant galaxy cluster, and animals such as the quagga and Yangtze finless porpoise. The biographical notes encompass figures like Lawrence, Sarah Baartman and Chinese scholar and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo.

The book is the outcome of library-scouring, note-taking, interviews, bar conversations and Google searches by Strachan and a group of collaborators. Its contents are bound in navy-blue leather with the overlapping letters “E” and “I” gilt-embossed on the front. This insignia also appears on the numerous crates used as plinths throughout the exhibition.

The Return is the product of two visits to South Africa. It explores ideas of physiological and psychological return in relation to the repatriation of cultural artefacts to Africa. There are additional choreographed surprises, meaning the exhibition is only viewable by appointment.

Spoiler alert: the Encyclopaedia of Invisibility appears early in the exhibition. Its prominent positioning is important as the book materialises a central working concern for Strachan — the recovery of invisible facts and histories.

The book’s origin is directly related to a career-defining feat of ingenuity and hustle. In 2005, Strachan shipped a 4.5-tonne block of ice from Alaska to his former junior school in Nassau, where it was displayed as a refrigerated truth. Titled The Distance Between What We Have and What We Want (Arctic Ice Project), the sculpture led to Strachan learning about African-American polar explorer Matthew Henson, a co-discoverer of the North Pole in 1909.

“Henson was the reason why I made the encyclopaedia,” said Strachan when we met the day after his opening. Tall and bearded with Mohawk haircut, he wore a raffish scarf with his T-shirt. His arms were knotted for much of the interview.

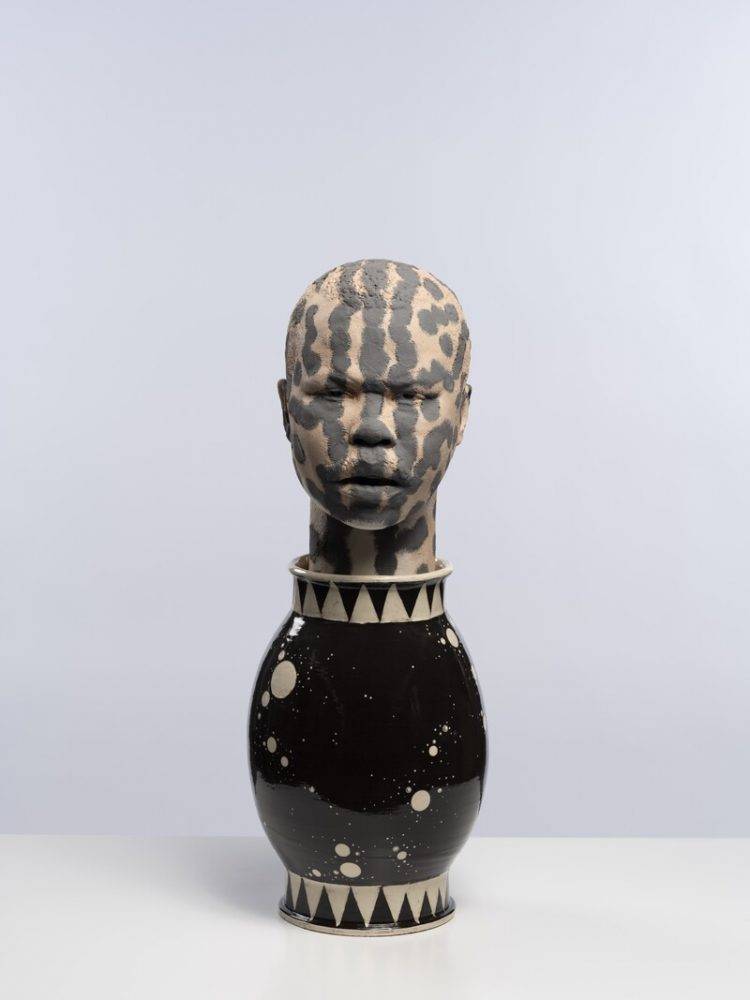

‘Head and Pot (Louise Little: Leopard)’ . All images courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

‘Head and Pot (Louise Little: Leopard)’ . All images courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

‘Head and

‘Head and

Pot (Marcus Garvey: King Cheetah)’. All images courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

“If Henson is not something being taught or the subject of filmmaking or any kind of generalised information, what else isn’t and why?”

Strachan’s question rehearses one asked by writer Mark Dery in a well-known 1994 essay: “Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?”

“Yes,” Strachan’s work proposes.

His commitment to recovering arcane facts and lost histories propels his faith in the future. Its display also highlights a contradiction. His codex of reclaimed facts is installed under Plexiglas. It cannot be browsed. Its secrets are mute. This prompted some flailing on my part.

Unlike the Whole Earth Catalog, a hippie Wikipedia in magazine form first published in 1968, I told Strachan, or The Negro Motorist Green Book, a printed guide to lodgings, businesses and petrol stations amenable to black motorists issued between 1936 and 1966, his book is inaccessible.

“But is it?” he responded. “Is it just the object you saw or is it a story, a thought experiment about human consciousness or a conceptual artwork? Does the idea of it change how you think about information?”

This is Strachan the conceptual artist speaking, not Strachan the encyclopaedist. Is it fair to distinguish? Not really. Strachan’s encyclopaedia enacts what Ralph Ellison, in the charged opening to his debut novel Invisible Man (1952), describes as the human need “to convince yourself that you do exist in the real world, that you’re part of all the sound and anguish”.

“I am an alien operating in the art world,” Strachan told me. “I’m in a world that has usually ignored my people. I’m operating in a foreign space, and if I want to not continue to be an alien, I have to bring ‘my people’ into this space to create a kind of playing field where a more complicated dialogue about human socialisation can exist.”

Ellison forms part of Strachan’s canon of black existence and initiative that is variously figured and invoked in The Return.

“Ellison reminded us that invisibility comes from a refusal to see,” writes Strachan in the foreword to his enclosed encyclopaedia big book. “As it turns out, learning to see again can take time.”

Some say the encyclopaedia took five years to produce. Strachan, who first visited SA in 2021, said the version on view in Johannesburg captures 16 years of labour. Whatever the precise number of years, the book and its evolving mythos evidence Strachan’s ambition to be a long-form storyteller. He cites artists David Hammons and Bruce Nauman, as well as jazzmen Miles Davis and Sun Ra as precursor examples.

‘Encyclopaedia of Invisibility’, from Tavares Strachan’s exhibition ‘The Return’.

‘Encyclopaedia of Invisibility’, from Tavares Strachan’s exhibition ‘The Return’.

“If you look at Miles, his career is an example of someone who is a long-form storyteller. It all makes sense as one story but it doesn’t take shape until the end.”

Strachan’s story begins in Nassau, where he was born into modest circumstances in 1979. The second of six boys, he favoured growing plants over reading sci-fi.

“I spent time in the landscape gardening, making and watching things grow, learning about growth, understanding maturity,” he said. “Growing up in the conditions I grew up in, sci-fi was not a high-priority item.”

His decision to study painting at the University of the Bahamas caused anguished gasps from his family. An alien at home, he decamped for the US, where he switched his focus to glass sculpture at the Rhode Island School of Design. In 2006, he completed a master’s degree at Yale University.

Strachan represented The Bahamas at the 2013 Venice Biennale but only generated real notice in the late 2010s when he started exhibiting his Encyclopaedia. “It’s not meant to replace Britannica,” he told The New York Times in 2019, when it went on show in San Francisco. “It’s an alternative document.”

A nod from Artforum greeted a 2020 showing of it in New

York: “Strachan’s message feels expansive and hopeful.”

The praise was bookended in last year with the award of a MacArthur Fellowship for “expanding the possibilities for what art can be and illuminating overlooked contributions of marginalised figures throughout history”. Strachan got a no-strings-attached cash prize of $800 000.

For an artist who came to prominence foregrounding invisibility, Strachan is incredibly visible. When I quizzed the artist about this, he untied his locked arms.

“The visibility has, in some ways, been difficult,” he candidly offered. “With visibility comes expectation. It is one thing to fail when no one is looking but another thing to fail when everyone is looking. It requires more courage.”

‘Unsustainable Kindness’ from Tavares Strachan’s exhibition

‘Unsustainable Kindness’ from Tavares Strachan’s exhibition

His exhibition has divided early viewers. Some have been seduced by the eye-tingling collage aesthetic of his ceramic sculptures, tapestries (produced locally by Stephens Tapestry Studio) and light paintings. Others were put off by his Woza Albert!-style exploration of restitution debates and identity politics. I can see the truth in both positions, but prefer a third opinion.

This year, South Africa has hosted an astonishment of American riches. Strachan’s exhibition follows on enlightening showcases by artists Faith Ringgold and Leonardo Drew, both at the Goodman Gallery. This weekend, Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town closes When We See Us, its pop-infused survey of a century of black figuration that features prominent historical painters like Aaron Douglas and Beauford Delaney.

But is it fair to group Strachan with these American artists? Is he not a Bahamian artist living in the US?

“It is a struggle,” he conceded. “I’ve been gone from home for a long time. It obviously has an impact. I think I was always a foreigner, even when I was home. It always felt like I was going to go somewhere.”

His big book, with its sublimated map of family relations, is his valid passport to that somewhere.