Pebofatso Mokoena’s notebooks form part of an interactive group show in Johannesburg

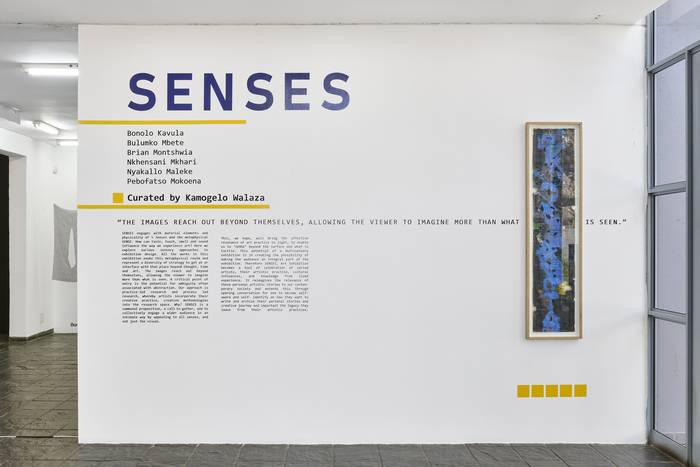

The moment you walk into the gallery space at the Goethe-Institut in Johannesburg, you are met by the Senses exhibition, which captures the mind, heart and, of course, the senses.

The exhibition is presented as part of the Young Curators Incubator programme — an initiative conceived by the Goethe-Institut in collaboration with the University of Cape Town’s Michaelis School of Fine Art. It is curated by Kamogelo Walaza.

During a private walkabout, Walaza explains some of her curatorial choices for the exhibition, which displays the work of six multidisciplinary artists, carefully chosen to tell their stories. They are Bonolo Kavula, Brian Montshiwa, Bulumko Mbete, Nkhensani Mkhari, Nyakallo Maleke and Pebofatso Mokoena.

Some background. Senses is a group exhibition that engages with the material elements and physicality of the five senses — how taste, touch, smell, vision and hearing influence the way we experience art.

The exhibition does awaken the senses as you make your way through each of the artists’ contributions.

I am moved to touch Mbete’s work, which is what you encounter as you walk in. They are contemporary works made of materials such as denim and itshali (a type of blanket worn by brides on their wedding day).

Walaza quickly cautions that this work cannot be touched, just admired with the eyes: “There are works that people can come into contact with, while others can be admired by just looking at them.”

She emphasises the importance of the relationship between the curator and the artist and says there should be open lines of communication at all times. That, ultimately, creates an environment where the work is showcased with the utmost respect.

The importance of this back-and-forth surfaced when she wanted to suspend one of Montshiwa’s installations to display it on the exhibition.

“I felt that it would have been stronger,” she says. However, the artist explained that hanging referenced a past experience with a loved one. Walaza knew that she had to listen and respect Montshiwa, regardless of her curatorial desires.

“These are the types of angles you look at as a curator when you negotiate with an artist. That’s why I say social practice is important, in as much as this is the work coming into the space and, now, I take a level of ownership of the work.

“It is very important to have those interactions with artists to make sure that they are okay and they trust that their work is there with you.”

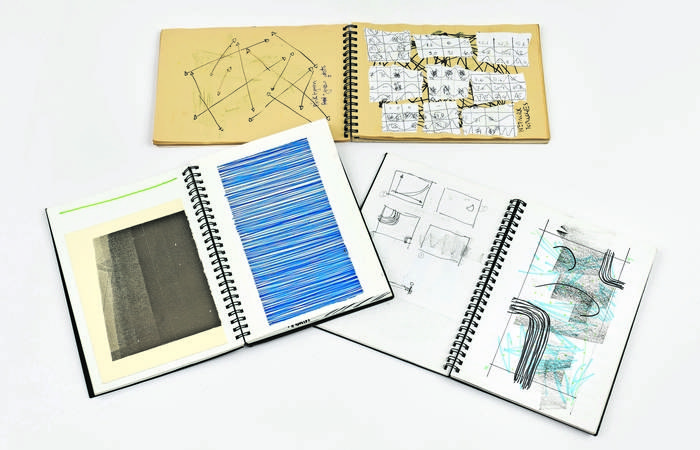

The exhibition ends with an interesting piece of work. For it, notebooks are carefully and skilfully placed. They are simply displayed. Some stand neatly on a block of wood, while others are strategically placed against the wall. They are calling to one of my senses.

“Can I touch this?” I ask. “Absolutely,” replies Walaza.

I open one of the notebooks, dated 2016. Every page is filled with abstract illustrations.

She tells me, “This work belongs to Pebofatso Mokoena.”

Walaza explains that Mokoena has been travelling between his hometown of Alberton and Johannesburg for years, using public transport. A lot of the illustrations are about how he experienced the city.

“Every day I come here, open a notebook and find something new. I am always amazed at what I find in these books,” says Walaza.

I drop a notebook by mistake and panic. But Walaza tells me: “Don’t worry — this is a curatorial choice.”

My next mission is to track down the man behind the notebooks to paint an image for us, to place us where he was, tell us what he was feeling, at the time of making them.

On a hot Tuesday afternoon, Mokoena and I sat for almost an hour at the Salvation Cafe in Milpark, talking about his process and work. He is soft-spoken and I started to regret the choice of venue because we made it to the café just in time for the lunchtime rush.

The 30-year-old tells me he was born eight months before South Africa’s first democratic elections in April 1994 and shares his first memorable encounter with the arts.

Take note: The Senses exhibition, on at the Goethe-Institut Johannesburg in Parkwood until 29 February, showcases the work of Pebofatso Mokoena

Take note: The Senses exhibition, on at the Goethe-Institut Johannesburg in Parkwood until 29 February, showcases the work of Pebofatso Mokoena

“I used to watch quite a bit of TV and draw. Other kids would draw cars and houses; I would just draw lines but I never really knew what those lines were,” he says.

Mokoena says his love of drawing was so evident to his family that they bought him a 72-page book in which he would draw figures and lines.

“That meant everything to me. There was something about having a book and a pen where I could just do whatever I want on a page. That was one of the best things ever — it was not the ultimate freedom but a licence to build what I wanted and no one could tell me it’s wrong,” he says.

He matriculated at Alberton’s Bracken High School in 2011 with a distinction in visual art and the Design School Art Trophy.

Mokoena would go on to study visual art at the University of Johannesburg and got his bachelor degree from the University of the Witwatersrand with distinction. He is studying towards a master’s degree in fine art.

According to his page on the Latitudes Centre for the Arts’ website, his work “orbits in between critical discourses across the spheres of visual art architecture, global culture and aesthetics”.

“These interests at times open and bridge gaps in his own understanding of the importance of being alive in a world that, in theory, in becoming smaller and smaller.”

Mokoena’s work also taps into why people move from one space to another and the way they move.

Although he uses many media, he says pen and paper is his favourite because they are limitless.

What we see in the notebooks on Senses is him trying to make sense of where he was, to figure things out, as he felt he was operating in a very complex space, being the city.

“I could not articulate what capitalism, communism or socialism was, but I could articulate the movement of people from one space to the next, or the movement of taxis.

“I did not know I was mapping those things out and that I was creating diagrams,” he says.

Pebofatso Mokoena’s notebooks form part of an interactive group show in Johannesburg

Pebofatso Mokoena’s notebooks form part of an interactive group show in Johannesburg

The notebooks grew over time as he navigated the city, and when Walaza approached him about an interactive show she was working on, he started thinking about how to put a collection of works together.

“The books were the initial idea but Kamo [Walaza] wanted us to take it even further. We pushed it further until the final week but we did not have anything to show.

“We knew we needed to get it together very quickly and we knew we had to go back to the original idea — the books,” he says.

The exhibition’s works flow well into each other. If you did not know it was a group show, you might think the work was by one artist — showcasing Walaza’s curatorial prowess.

“When you encounter art, drop all your baggage at the door. Get into the work with the least amount of assumption,” Mokoena says.

His notebooks, a highlight of the show, invite viewers to connect with his personal reflections on the movement and space of the city, providing a unique and intimate experience for all who engage with this captivating showcase of sensory exploration.

The exhibition runs until 29 February at the Goethe-Institut Johannesburg in Parkwood.