Taking wing: Time Flies by Sutapa Biswas, who moved from India to England as a child, uses images of birds, some imaginary, some real-life studies, to look at issues around migration. It is part of the Ecospheres exhibition at the Joburg Contemporary Art Foundation. Photo: Graham De Lacy

Our guide lowers her voice: “It’s a very sensory and meditative space. I will encourage you to walk through the space carefully to get a glimpse of it and experience it.”

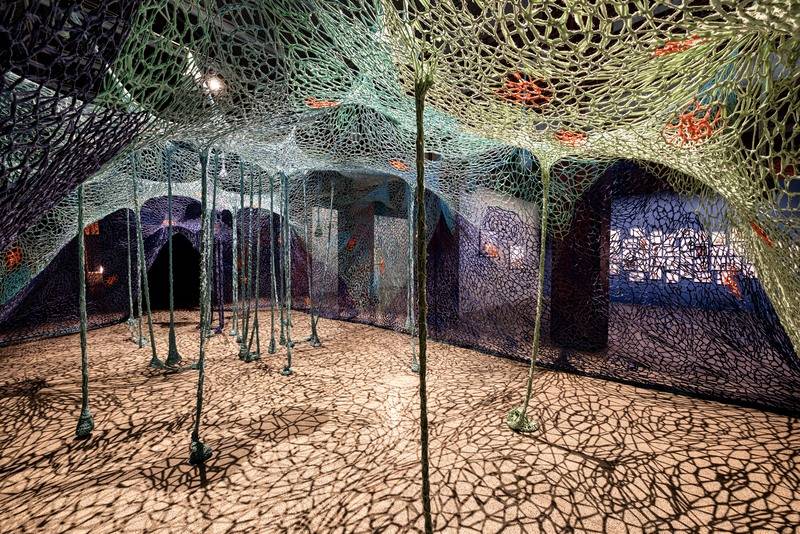

We respectfully enter the installation, which is titled One Day We Were All Fish. It’s a large-scale sculpture, a knitted cotton net in shades of green, purple and aquamarine, that convincingly mimics the idea of being under the ocean.

We weave between sock-like contraptions — I quickly count 30 of them — that hang from the top of the net to the floor throughout the installation. The net throws speckled shadows on the floor.

Outside, in the rest of South Africa, the winter blues are setting in, votes are being counted, anxieties are rising, but in here there is a sense of calmness and peacefulness.

The respected Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto’s installation is part of the Ecospheres exhibition that has just opened at the Joburg Contemporary Art Foundation in the city’s suburb of Forest Town.

Ecospheres aims to address the topics of ecology, the environment, climate and the natural world, where humans are to live as part of a harmonious interaction between all living creatures.

Based on the elements of water, air and earth, the exhibition is divided into three “atmosphere” rooms.

We are on a media tour through the breathtaking show the evening before it opens to the public on 31 May. We are each armed with an informative reader, which explains this exhibition is part of a three-year theme of “world-making”.

A trilogy of exhibitions — Ecospheres, Structures (next year) and Futures (2026) — will explore concepts around the environment, sustainability, architecture, habitat and biotechnology.

Our superb guide Maxine Maistry tells us Neto has been fascinated by the ocean since early childhood and this has grown over time.

His installation is in the water atmosphere room.

“He’s thinking about the ocean as a mode of connection, a way of connecting people and culture and knowledge,” Maistry tells us, “and it’s not just something that carries vessels.

“It’s not just about the physical journey but also about the people that move across the ocean … how the ocean can become a point of reference and also a point of connection.”

The work, which forms part of Neto’s series The Earth’s Belly, is made from traditional African and Brazilian textiles.

Unearthing culture: Peruvian artist Ximena Garrido-Lecca’s Botanical Insurgencies, which involves a method of cultivation used in Moche culture (left), and Brazilian Ernesto Neto’s installation One Day We Were All Fish (right). Photos: Graham De Lacy

Unearthing culture: Peruvian artist Ximena Garrido-Lecca’s Botanical Insurgencies, which involves a method of cultivation used in Moche culture (left), and Brazilian Ernesto Neto’s installation One Day We Were All Fish (right). Photos: Graham De Lacy

The way this fabric has been connected, Maistry tells us, “can be a very complex root system. Think about how that might relate to personal roots that are also below the surface. I can look at you and get a very general understanding of who you are but I don’t get to see what’s below your surface.

“There’s a whole other person and identity that’s wrapped up in those roots that are below.”

Roots are also investigated by one of the artists in the water atmosphere space. Cape Town ceramicist Zizipho Poswa explores her Xhosa culture through her artistry.

Her work on display, a striking abstract sculpture titled Mzingisi’s Mother, looks at the traditional ways of carrying and collecting water, but she’s also about Xhosa women and the developmental roles they play in their community, whether that be physically, spiritually or mentally.

Maistry goes on to explain: “She’s drawing on this relationship of vessels — how this literally is a vessel that can contain and collect water but at the same time think about how a mother is a vessel for life. And how human beings are also vessels for our own histories and stories that we carry through us.”

In atmosphere room two, air is explored in relation to migration, diaspora and kin.

Ethiopian photographer Michael Tsegaye has two works on display. The first is a black-and-white photo, from the 2007 series Ankober, named after a place in Ethiopia. The image shows ghost-like figures on the move through air over-saturated with water.

The second, a contrasting photo, comes from the Afar II series. Afar, in Ethiopia, formerly known as Region Two, is one of the hottest places on Earth. It’s home to a volcano and to lava lakes, very dry and prone to drought and sandstorms.

“If you come closer, you’ll notice the very fine detail in the foreground. It’s almost like you can feel how brittle the sand is and imagine how it feels when it’s hitting your skin,” says Maistry.

“So, you get to see how situations like this might prompt migration and encourage people to move.”

The works on the adjoining wall get you to understand migration in a very different way. Titled Time Flies, they are by Sutapa Biswas — 57 acrylic and pencil on paper, framed portraits of birds — some imaginary, some real-life studies.

Biswas was born in India but, at the age of four, she moved to England with her family.

Time Flies relates to diasporas and the migratory paths of those who survive the turbulent, violent histories of empires. It was inspired by the last conversation she had with her father, shortly before he died.

She describes her father being strangely bird-like — they discussed birds, with particular reference to a passage from Marcel Proust about the sound of a wood pigeon cutting through the forest.

The paintings are hung on a rich, dark blue wall. This comes from a memory of Biswas’s mother wearing a blue sari and reading a blue aerogram letter … and how she saw this and thought it was one of the most beautiful things she’d seen.

Biswas came across this memory again later, as she was completing her tertiary studies, prompted by the painting by Johannes Vermeer titled The Woman in Blue, in which a woman reads a letter.

Biswas did some research and found out that specific blue pigment came from a type of rock called lapis lazuli, which is common on the Indian subcontinent. It speaks to how, like people, materials migrate.

Roots also feature in the earth atmosphere room, and literally so. South African photographer Russell Scott’s Botanical Portraits Unearthed is a series of scientific photographs of indigenous plants from across Southern Africa.

The plants needed to be unearthed for Scott to photograph them, our guide explains, and the process was sometimes dictated by the plant.

Scott’s wife would often caution him to not take the plant out yet: “They’re not ready to be removed. If you do take it out, it’s going to die.”

His intention was to take the plants out and then return them to their natural habitat.

Across the room is a five-channel video piece by British-Nigerian conceptual artist Zina Saro-Wiwa. Her father Ken, the Nigerian poet and author, became well-known as a human rights and environmental activist. He was executed in 1995 by Nigeria’s military regime when Zina was 19 years old.

Her work about unscrupulous resource extraction is titled Karikpo Pipeline. It superimposes a performance by traditional dancers onto video footage and photos of a disused oil pipeline in Nigeria.

It is also in contrast with the cultural life of her Ogoni people.

The process of installing the pipeline in the first place was invasive and violent — ecosystems were disrupted as the soil was moved to make way for it. Although it’s not being used, it is still leaking substances into the environment.

“It’s damaging the soil and the land around it,” says Maistry. “That shows the contrast of what happens when you take care of soil and what happens when you don’t.”

When we enter the adjoining room, there are gasps all round from the media contingent. At first glance, it seems as if you are entering a compact, brightly lit boxing ring with a steep pavilion on three sides.

It is the work of Peruvian artist Ximena Garrido-Lecca, and involves growing lima beans hydroponically. It gives meaning to live art, not to mention living nature in an art gallery.

The climbing plants obtain their nutrients through a solution, rather than through soil — the 12 rows of earth-coloured clay pipes give the impression of a grandstand.

Six months in the making, Garrido-Lecca’s installation, which is titled Botanical Insurgencies, references the system used in the Moche culture, carried from a pre-Incan Peruvian society which made use of complex irrigation systems.

With this contemporary hydroponic system used to grow the age-old plant, the artist is reviving the Moche ceramist tradition.

In another part of the installation, Garrido-Lecca has a mural of an ideogrammatic writing system which is part of the way in which people in the Moche culture communicated.

It proposes a translation of a colonial text titled Edict Against Idolatry, in which the Spanish priest Jose Arriaga lists the practices that should be eliminated from the Peruvian tradition, including the worshipping of plants.

Planting ideas: South African photographer Russell Scott’s Botanical Portraits Unearthed.

Planting ideas: South African photographer Russell Scott’s Botanical Portraits Unearthed.

After our guided tour — which included several other provocative works not mentioned here, due to limited space — I ask Bárbara Rousseaux, the gallery’s project manager for Latin America, to chat more about what they hope patrons will take from Ecospheres.

“I think, for me at least, it is a positive feeling.

“While we have all these different, perhaps problematic issues covered, overall, I feel we still have all of this around us, and we can still be better with, and live alongside, nature in a more harmonious way.”

She describes Biswas’s work as “this idea of migration … but some of those birds are also imagined, so it’s this idea of we live in this world with all of these other beings’ experience”.

“Similar experiences in terms of perhaps displacement and building a home in different contexts — in her case it was her family migrating from India to the UK.

“And I think that’s hopeful, and sometimes it could be a bit nostalgic, but there’s also hope in some of the works,” Rousseaux says.

We have found our way back inside Neto’s installation.

“What is the wonderful smell?” I ask her.

“Cloves,” she says, with a smile.

The contraptions that hang throughout the installation are filled with various things: linseeds, semi-precious stones and aromatic cloves — which are often used in traditional medicine.

That must explain why I feel so content in Neto’s installation. Surely, it can’t still be the wine I had earlier before the guided tour started?

Later, I read on the American Tanya Bonakdar Gallery’s website that the Rio-born artist’s influential body of work — which has been exhibited in major venues worldwide — “explores constructions of social space and the natural world by inviting physical interaction and sensory experience”.

Drawing from biomorphism and minimalist sculpture, along with Neo-Concretism and other Brazilian vanguard movements of the 1960s and 1970s, the 60-year-old Neto both references and incorporates organic shapes and materials — spices, sand and shells among them — that engage all five senses.

It produces a “new type of sensory perception that renegotiates boundaries between artwork and viewer, the organic and manmade, the natural, spiritual and social worlds”.

Neto’s, and the other works on display, make you want to spend time in Ecospheres. In a stage when environmental and climate issues are global concerns, the exhibition is essential.

While it is compelling and, dare I say, even entertaining, it is by no means escapist. It is serious and it is clear as daylight that we are facing a climate crisis. But the works are transportive with stories and imagination.

As the exhibition’s reader says: “Stories are not just representations of reality, they are makers of reality. And artists are makers of worlds that represent both the natural and imaginary.”

Ecospheres is on show at the Joburg Contemporary Art Foundation until 7 December. Booking is essential.

Ankober and Afar II by Ethiopian photographer Michael Tsegaye. Photos: Graham De Lacy

Ankober and Afar II by Ethiopian photographer Michael Tsegaye. Photos: Graham De Lacy

TV series provided exhibition’s curator with food for thought

The impetus for one of South Africa’s most ambitious art exhibitions started with a Netflix series on food. Clive Kellner, the executive director of the Joburg Contemporary Art Foundation, has a mischievous smile on his face.

“So, the secret is now out — I was watching Netflix and it was Chef’s Table … I secretly loved that series, and I came across a restaurant called Central,” Kellner says.

“This amazing chef, Virgilio Martínez, creates these dishes on the topography of the landscape of Peru. So, we thought, ‘This is amazing, they’re making art … It’s food but it’s art.’”

Curator Kellner is addressing us at the media opening of Ecospheres, before a guided tour of the exhibition that will run until 7 December. It forms part of a trilogy of annual exhibitions.

(Central, by the way, is the global top eatery, as judged by the prestigious The World’s 50 Best Restaurants 2023 awards. It featured on the Chef’s Table series in 2017.)

Martínez opened Central in Lima in 2008 with the vision of creating a fine-dining experience rooted in Peruvian ingredients and cooking techniques, according to The World’s 50 Best Restaurants 2023.

Pía León joined in 2009, going on to become Martínez’s head chef — and wife.

“Martínez and León share a deep passion for the Peruvian pantry, so contagious that even Martínez’s sister Malena was brought into the fold to head up Mater Iniciativa, the restaurant’s research arm,” 50 Best writes. Mater works with indigenous communities across Peru.

Kellner went there to experience Central’s high-level culinary experience.

“So, we reached out to them, we thought it was worth the chance,” he says. “Let’s see if they’ll collaborate with us in an art exhibition. So, we did a Zoom call and they responded positively.”

The result is five installations relating to Central and Mater on show in the Ecospheres exhibition.

I ask Kellner about his 14-course meal at Central.

“I photographed every dish,” he says. “It’s a fusion of sophisticated culinary with indigenous knowledge and cuisine which is from the natural environment.

“The chef really created this menu based on the topography, the landscape of Peru … the ocean, all the way up into the Andes.”

And taste-wise?

“You feel light and kind of sensual and very sensory of the eating. Each serving comes with different cutlery and crockery, and different servings with different explanations.

“They’re working in a very sustainable, ecological way and working with communities as well.”

Kellner says some of the food and source material is medicinal, used by communities for healing stomachs, for wounds. “So, it’s really incredibly potent but an incredibly visual and sensual experience going through those dishes.”

I ask him about “healing”, how he kept that in mind with curating Ecospheres, seeing that it is easy to be despondent about what’s happening to our world.

“That was the first problem — every exhibition on ecology or environment is negative,” Kellner replies. “It’s doom, it’s the end of the world.

“I completely understand the urgency, we all do, but I didn’t want the audience to come out feeling there’s no hope, and that there’s a way to contextualise those debates.”

They used the very informative reader for that.

“But the artworks are [also] part of the sense of hope — another word for healing.”

We can learn from nature and what artists do with it in the artistic imagination, he says.

“So, nature can teach us so much — there’s a restorative, human custodianship element in the exhibition. The people come out feeling, ‘Hang on, I need to take responsibility for nature, this is an incredible gift we have.’”

But, says Kellner, the exhibition is not overly didactic: “We’re not trying to say: ‘We know everything and will teach you everything.’”

The exhibition is an immersive experience that includes installations of hydroponic plants, oceanic-inspired knitted textile, botanic photography, sound and meditative paintings of migratory birds.

“The kind of imagination that the artists have employed in discovering and exposing ideas around the various natural elements, it’s really uplifting,” Kellner concludes. — Charles Leonard