Admire Kamudzengerere

A strutting cockerel, adorned with cartoonishly elongated wattles and comb, is an idiosyncratic feature of the artist Admire Kamudzengerere’s oeuvre.

The anthropomorphic cockerel — jongwe in Shona, Kamudzengerere’s mother tongue — has become one of the most striking symbols in Zimbabwe’s recent visual history.

Kamudzengerere’s rooster first got recognition in a 2006 competition held by the Spanish embassy in Harare on the 400th anniversary of the birth of Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes, author of the canonical Don Quixote.

The artist’s stylistically assured entry, Rocking Don Quixote, depicting a brooding rooster with giant wings flapping in the slipstream of a horse, was awarded first prize for Best African Perspective. Later that year, he came third in a competition held by the local Netherlands embassy to mark Rembrandt’s 400th birthday for his piece Dutch Master Cockerel Lesson.

The work shows a Stetson-wearing rooster, a chess board laid out before it, as human figures stare at the bird in suppliant silence. Has a more self-confident pedagogue ever graced our lecture halls than the one Kamudzengerere conjured in Dutch Master Cockerel Lesson?

If the rooster appeared to come out a fully formed protagonist in the emerging artist’s work, immediately winning him plaudits, it was because, in Kamudzengerere’s imagination, its image was already as clear as the crowing of the bird each day to announce dawn.

The figure came to him in the early to mid-2000s, a period of learning and honing his technique; it was also a time when he found his voice and a corresponding visual vocabulary, thanks to the advice of his contemporaries and the crucial feedback he received from the now-late couple Helen Lieros and Derek Huggins, co-founders of Gallery Delta.

The fowl is not a close companion of human beings, like the dog, nor a store of value, like the cow yet, since its domestication 8 000 years ago, the bird has played an important role in the rhythms of man and woman. The rooster marks temporality, fighting the dictatorship of the night, announcing dawn when humans are still weighed down by sleep.

For its role in being the first to spy the streaks of the new day and setting our routines, some political organisations, including in Zimbabwe and Malawi, have adopted it as their symbol. However, the rooster of Kamudzengerere’s imagination isn’t the bird that would have roamed his ancestral rural home in Zvimba, 80km south-west of Harare, not far from former president Robert Mugabe’s homestead in Kutama. If the artist had conjured a macabre and hulking jongwe, it would still be wild, roaming the forests.

In Kamudzengerere’s world, the cockerel is a figure of authority, not just a cog in horology. Animals — the cockerel, the (scape)goat, the elephant and even a mythological creature that is part fowl and part rhinoceros — routinely appear in his work.

Could his fascination with animal life, the wild, trees (especially the baobab and muhacha) and agriculture be the origins of the moniker “Animal Farm”, a term evoking the satirical novel by English novelist George Orwell, by which his forested working space-cum-artist residency in Chitungwiza is known?

Although Kamudzengerere’s work is getting critical acclaim and winning awards, he was still unknown to some. For instance, when the then-deputy director and curator of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, Tapfuma Gutsa, held a show featuring the works of Portia Zvavahera, he included her contemporaries and friends.

The January 2010 exhibition, titled Portia and Friends: Under My Skin, featured Gareth Nyandoro, Munyaradzi Mazarire and Masimba Hwati. Gutsa realised only afterwards that he had forgotten to include an important peer: “I am missing out someone,” he thought, “for [where] was Admire?”

To rectify this, he invited Kamudzengerere, born in 1981, to stage his inaugural solo display at the national gallery. Titled The Fifth Column, the show was held in late 2010, and comprised drawings, paintings and prints. It’s a measure of how much he was rising as a creator that the national gallery presentation was, in fact, his second solo effort in 2010.

Kamudzengerere had waited for years for a solo exhibition and then two took place at once. His debut, Variations in the Game, was at Gallery Delta in June of that year.

I asked Kamudzengerere why his national gallery exhibition was named The Fifth Column. “You have to ask Gutsa,” he replied. “It was his idea.”

So I duly paid the acclaimed artist Gutsa a visit to find out.

“In war theatre, the units are known to each other, except for the fifth column,” Gutsa told me as we traversed his property, which boasts a sculpture park, artist residency, studio and orchard, in Murehwa, 100km north of Harare.

Gutsa didn’t go into a dictionary definition of the term, which was first used in the Spanish Civil War (1936 to 1939) and refers to a clandestine group or faction of subversive agents who attempt to undermine a nation’s solidarity by any means at their disposal.

In naming the exhibition The Fifth Column Gutsa, a perspicacious thinker, was identifying one of Kamudzengerere’s key traits — his self-effacing demeanour, the quiet way he goes about his life and practice.

It was a characteristic first noticed by his high school art teacher, the painter Eugene Mugocha, who described him as a “silent blast”.

Kamudzengerere “is there, he is present, he is confident — but he is not loud”, Mugocha observed.

It’s not a surprise, then, that in the memorable line-up of his Portia and Friends contemporaries, Kamudzengerere was absent. Even though Gutsa and Kamudzengerere had spent time together in Harare’s bars, Gutsa “had not known about [him] and [his] work”.

In many ways, Kamudzengerere is a kind of fifth column, an underground operator, by turns self-eliding, subversive and elusive. He reminds me of a memorable opening line in a poem by the Irish Nobel laureate poet Seamus Heaney: “I moved like a double agent among the big concepts.”

Kamudzengerere shares his elusiveness with his hometown, Chitungwiza. Chitown, as it is popularly known, is a settlement about 30km south-east of Harare that grew to sate the appetite for black labour of what was then Salisbury, the capital of colonial Southern Rhodesia.

Present-day Chitungwiza inherited the name of the capital of the last medium of the spirit of the prophet Chaminuka, Pasipamire (the old Chitungwiza is sited near Beatrice, 50km south of Harare). According to oral tradition, Pasipamire was a miracle worker, a rainmaker who could hammer wooden pegs into granite boulders and conjure magical mists that made his capital invisible from invaders — the reason Chitungwiza was sometimes known as the “elusive city”.

Kamudzengerere might have evaded the spotlight for the first decade of his career, but he is no longer an unknown quantity. An alumnus of the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam, he represented Zimbabwe at the prestigious Venice Biennale in 2017.

He has also won the Northern Trust Purchase Prize at Expo Chicago in the US and the On Demand Prize by Snaporazverein, an art gong at Miart in Milan, Italy. But the moment Kamudzengerere has mastered a language is the very instant he wants to let go of it, or at least modify it.

The Swiss art historian Federica Maria Bianchi, chair of the jury that awarded Kamudzengerere his 2018 On Demand Prize, told me in an interview that his technique “is very special and I think it’s very unique” and comes out of deep reflection and research. “He modifies something, changing something, to combine them in a different way.”

Kamudzengerere’s personal philosophy is rooted in an antipathy towards self-repetition.

“I [like] the idea of continually questioning yourself. I can repeat something, but something has to change within that repetition,” he told me.

Take, for instance, the figure of the rooster. Its rendition now is less sinister as when it first appeared. It is benign, like the domestic rooster we all know and whose role is to mark time (and is slaughtered for the favoured visitor).

“We are all constantly searching for something — maybe new food, new music — but, for me, it is this journey of pushing myself a bit further.”

We are all on some kind of quest; most of us do it in desultory fashion but a few of us go about it as if it’s an edict from a savage god. Kamudzengerere belongs to the latter camp.

For those born south of the railway tracks, or, as they say in Harare, south of Samora Machel Avenue — the road that demarcates north from south, the suburbs from the ghettos — success isn’t preordained.

When Kamudzengerere enrolled for his advanced levels at Hatfield Girls High School in the late 1990s, in the formerly white suburb of Hatfield, he was venturing north out of the drudgery and dust of the ghetto of Chitungwiza. (The school’s advanced-level classes were also open to boys.)

He initially enrolled in maths, physics and chemistry — a career as a medical doctor or engineer beckoned — but switched after a semester to study business management, economics and accounting. His goal was to work in marketing.

Art was not Kamudzengerere’s first choice, nor his second, but his third, and even that was serendipitous. Sometimes he found himself in the school’s art department, where he was drawn into the orbit of art educator and painter Mugocha.

The teacher immediately saw Kamudzengerere’s talent. “His inclination was more towards drawing,” he told me in an interview at Prince Edward High School in northern Harare, where he now teaches.

A turning point in the master-student relationship was in the early 2000s, a period of intense domestic and professional pressure for Mugocha. He was preparing for an annual group show organised by Helen Lieros at Gallery Delta and was having trouble choosing two works to display.

He turned to the young Kamudzengerere for advice. “Those two, sir,” Kamudzengerere said, pointing at two particular pieces.

It was an intuitive pick, one Mugocha himself would have made had he not been distracted. Lieros was charmed by the pictures he had chosen. Mugocha saw that even at a young age, Kamudzengerere already had a natural affinity for art and the eye to discern what constituted a good painting.

“I knew from that point that there was something that could come out of the young man,” Mugocha said. Not long after, Mugocha introduced his young charge to Lieros, a highly regarded pedagogue and graduate of the prestigious Ecole des Beaux Arts in Geneva, Switzerland.

Kamudzengerere soon started attending weekend painting and drawing lessons. For the next decade, he had a close association with the institution, which culminated in his first solo show in June 2010.

Given how Kamudzengerere’s career has panned out, there are hints of prophecy in Mugocha’s observation, yet his path to success was littered with landmines and other ordinances — chiefly Zimbabwe’s socio-economic implosion.

The early 2000s were marked by hyperinflation and a collapse in living standards and many fled. Kamudzengerere, like the multitudes who left, could have chosen the path of exile, joining the cohorts of Zimbabwean artists who made South Africa home.

To survive in the neighbouring country, young creatives would quickly paint hackneyed colourful pictures of African sunsets, acacia landscapes and women carrying firewood, which they would hawk at traffic intersections in Johannesburg and Cape Town.

Did he ever think of joining his compatriots who were making “airport art”?

“If I had gone to South Africa, I [would not have known] where to start. At the time, I had Gallery Delta here; they helped me a lot. I was working at Delta, and having conversations with Helen and Derek helped.

“These two were not interested in that kind of art even though they understood it was an alternative for making money quickly. They feared that it ruined an artist’s career. Had I done it, I would have used another name. I didn’t want to be associated with that kind of work.”

Kamudzengerere stuck it out, stoically bore the worst excesses of that period, and became tough.

Often in life, as in the biblical parable of the Prodigal Son, the child who leaves becomes the centre of attention, for whom the fattened calf is slaughtered on their return.

Yet the son who stayed and diligently served his father for many years is never offered even a kid to celebrate an impromptu weekend braai with his friends. There is some poetic justice in that most of the current wave of exciting Zimbabwean artists stayed during the worst years of the crisis.

The sons and daughters who remained are now sitting at the table eating the fattened calf, their artworks selling for tens of thousands of dollars in the art industry’s famous auction houses and galleries in London and Basel, Milan and New York.

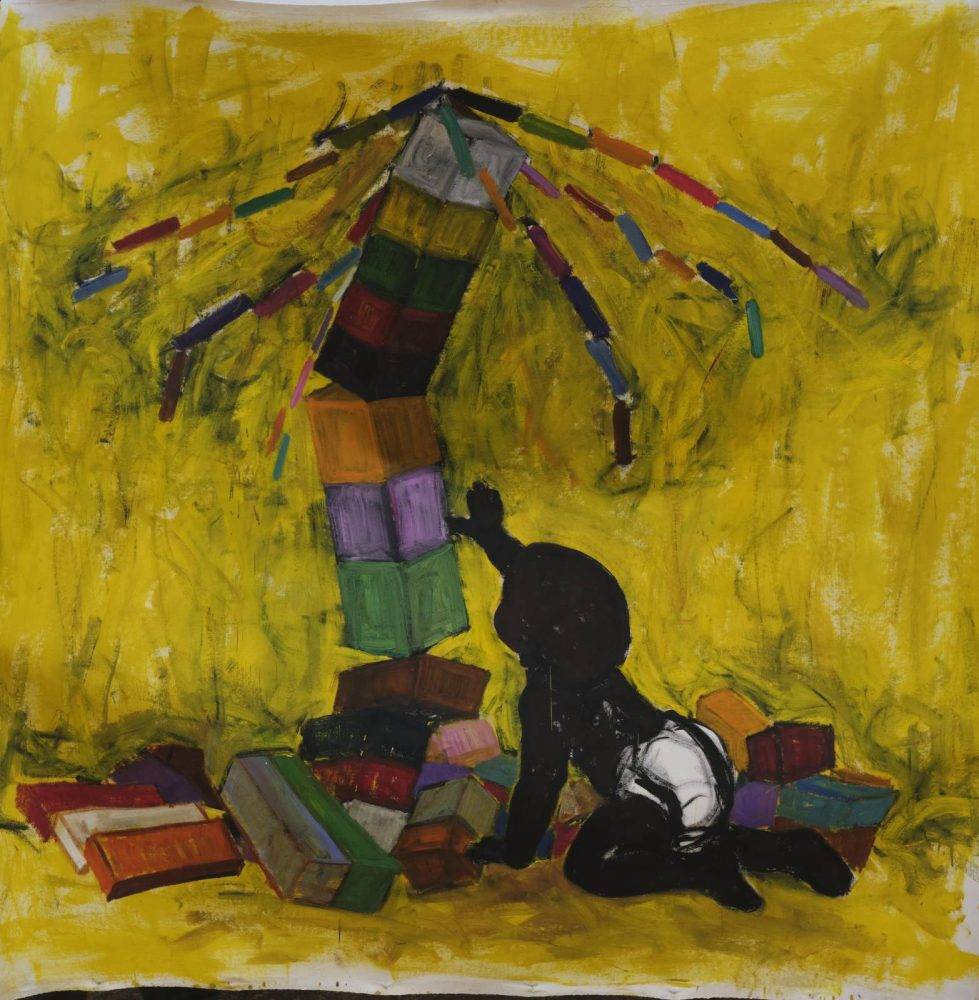

For Kamudzengerere’s display at the Catinca Tabacaru Gallery in Bucharest, Romania, in 2022, he painted “a bit” for the first time since 2013, a hiatus of about a decade. However, in Our Father’s Inheritance Doesn’t Allow Us to Sleep, the artist really makes a return to painting.

But even the phrase “a return to painting” should carry an asterisk. The artist hasn’t just picked up a dusty paint brush, dipped it in a thinning solvent and resumed where he left off. When Kamudzengerere was contemplating this show, he considered what he needed to do “to take painting to another stage”.

This exhibition is a response to a question he voiced to me: “What happens if I combine, if I experiment with, both painting and printmaking?” There was a desire on his part, to use a phrase he employed, “to go beyond painting”.

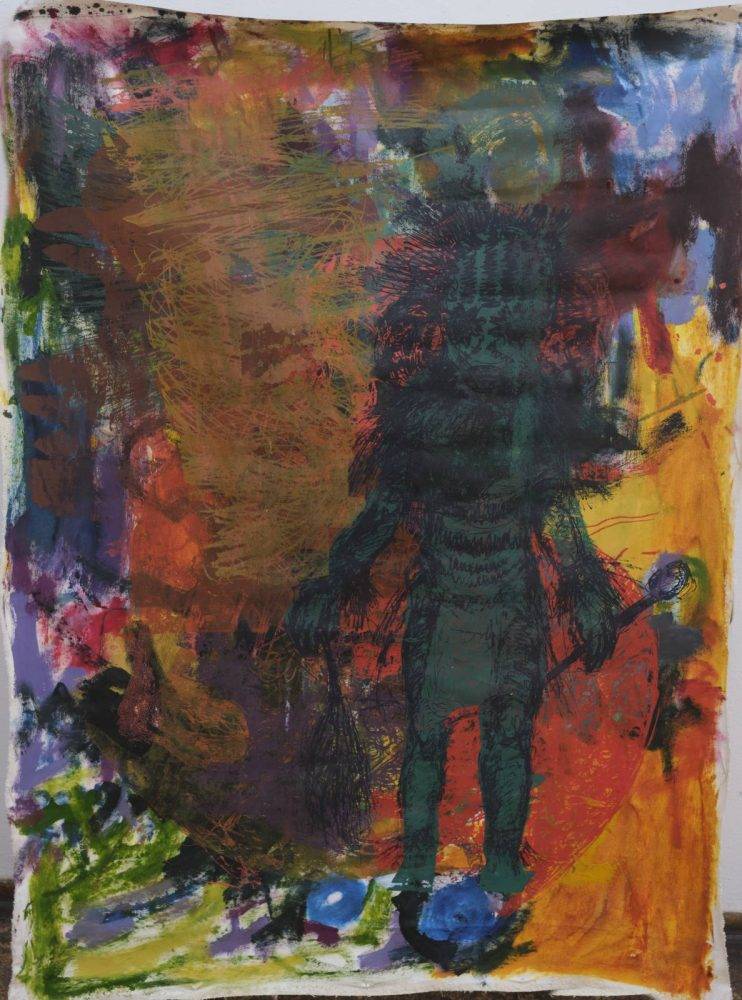

This preoccupation with technique, with form, was allied to a pressing question. In the past two decades in Africa, we have witnessed the phenomenal growth of shamans and healers, evangelical prophets and seers, who offer panaceas for a host of problems.

“I am looking at this theme where people are doing a lot of consultations at the [shrines] of shamans because they all have problems. If you really think about it, the problems they have are [to do with] health and financial issues.

The underlying cause is not bad spirits but has to do with a broken, collapsed system. But people do not wish to confront the elephant in the room,” he told me.

In Our Father’s Inheritance Doesn’t Allow Us to Sleep, Kamudzengerere eschewed merely presenting the visible extrusions of broken societies — hospitals to which people go to die; schools where no learning takes place; taps out of which water never comes — to explore African metaphysics and the proliferation of its protagonists, artefacts and attendant rituals.

With fresh paint strokes and the gaze of someone raised in a ghetto, he restates German thinker Karl Marx’s observation in his 1844 essay A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right that “religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering”.

“Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.”

The traditional healer Kamudzengerere depicts, whether wearing a ceremonial loincloth, nhembe, and wielding his knobkerrie, or clad in a shaman’s mask and costume, is dispensing the 21st-century substitute for opium, a palliative against all forms of pain and suffering.

Our Father’s Inheritance Doesn’t Allow Us to Sleep not only explores why people use opium, but — in its haunting beauty, riots of colour and bold experimentalism with form, content and technique — is a kind of opium itself, a beautiful thing to look at and lose yourself in when weary of all the ugliness on the continent.

This essay is taken from a catalogue accompanying Zimbabwean artist Admire Kamudzengerere’s National Gallery of Zimbabwe exhibition, Our Father’s Inheritance Doesn’t Allow us to Rest, put together by Percy Zvomuya, the designer Ricky Hunt and the photographer Khumbulani KB Mpofu. The publication was made with the support of the Embassy of Switzerland in Zimbabwe.