Phumi Morare says that passion, heritage and resilience have helped to shape her cinematic voice. (Photo supplied)

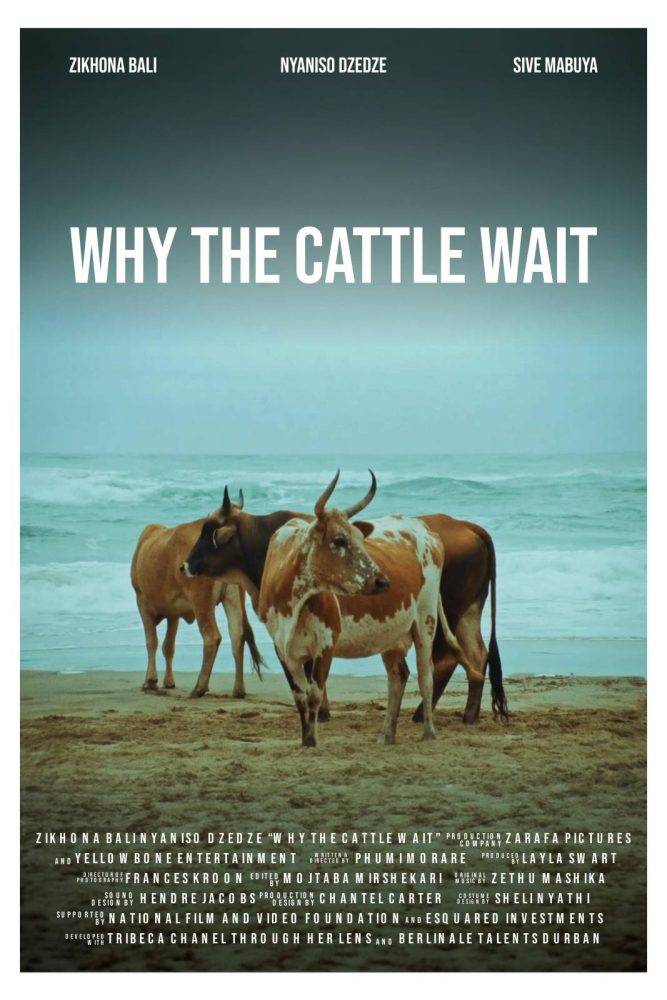

Award-winning South African writer-director Phumi Morare’s second short film, Why The Cattle Wait, is a folklore dark-light story set in the 1400s.

It explores a goddess who returns to Earth to find her mortal lover before the planet is destroyed.

“I’m interested in black female characters that are powerful in a quiet way,” Morare explains.

It’s a Tuesday afternoon, and I’m meeting her at her offices in Sandton, Joburg, to talk about her latest offering.

I’m keen to learn the steps she took to bring her to this point in her career, boldly exploring subversive black female characters on a global stage.

She still remembers the exact moment that made her want to pick up a camera and tell stories through the medium of film.

“The Shawshank Redemption was the film that made me say, ‘I want to be a filmmaker.’

“I was in high school, and I think because of the way my English literature teacher used to analyse films with us, I was just in awe of the process and the writer, how it was made and all of the thought that went into it and all of the meaning and themes and how they shot it to convey certain things.

“I was struck by the beautiful layers of storytelling and the fact that it’s also so moving and it just sits with you.”

“I decided I wanted to make something that just moves people and makes them think about things differently or makes them process something about life.

“My English literature teacher would play films and let us do film analysis during class.

“At the time, I was also doing a lot of theatre, speech and drama. I was writing plays and performing them and directing stuff.

“So when I started doing film analysis, I was like, ‘Wow, what a dynamic medium, that resonates specifically with me, of telling stories.’ So that’s when the idea started.

“But I never could see it as a career because I didn’t know anyone who was doing that.”

After matriculating, film wasn’t a choice for her tertiary studies.

“I was good at numbers, and the firstborn daughter, so there were expectations. I was scared to go against them, I guess. So, I went and studied finance.

“But when I was studying finance, I felt that itch for film.”

She started looking at part-time courses at institutions such as Afda but at the time they didn’t offer what she was looking for.

“I thought, ‘Okay, let me just bury this and focus where I am.’”

Morare got her first job in London at global investment bank Goldman Sachs, where she worked for a few years. And then she started feeling that itch for film once again.

“I started going to film festivals, doing short courses in London, meeting people in the industry.

“But I was still too scared to do anything about it. And then I thought, ‘Maybe I just need a career change.’ I was also quite homesick.”

Morare moved back to South Africa and took part in the McKinsey Leadership Programme for two years. It was there that the tide started to shift in her favour.

“My mentor at the time asked me, ‘Phumi, what are you passionate about?’ I told her, ‘I have this secret passion for film but I don’t know how to go about it.’

“And so, she introduced me to a few people and then I started exploring the reality of doing it.”

The leadership programme allowed participants to do internships externally to expose themselves to other industries. For Morare it was a no-brainer.

“I wanted to do it in film, and they let me, which was really cool. It was almost a risk-free way to explore.

“The great thing about that programme is it was giving us really strong consulting skills and exposure.

“But there wasn’t pressure for you to stay and be a consultant. It was more about building future South African leaders.

“That’s why they were open to people exploring different industries while they were doing their internship section. It was amazing.”

Morare spent the entire six-month duration of her internship working at a production company.

“While I was there, I knew this is what I should be doing, you know? Eventually, I spent months speaking with friends and mentors about wanting to take the leap.”

McKinsey gave Morare an offer to stay, which she took, but it wasn’t long before she felt that film itch yet again.

“That’s the problem. That itch keeps coming for you. One of my close friends said if you have a burning passion and you ignore it, you start to slowly die. I was, like, ‘Yoh!’

“Another friend helped, saying, ‘When you look back at your life, you tend to regret the things you didn’t do more than the things you did do. So, it’s okay to make mistakes because you’ll know, ‘At least I tried.’”

In 2017, Morare took a leap of faith and decided to go to film school at the Chapman University in California, in the US.

“I felt like I wanted not just to be on the business side of film, but creative and writing and directing. So, I went to film school in California to study writing and directing there.”

“I got help to go to film school as well because I got a partial scholarship from my school. I also got some grant funding from the National Film and Video Foundation. And then some of my savings. The Oppenheimer Memorial Trust was another of the funders.”

During her time at Chapman University, Morare developed her first short film, Lakutshon’ Ilanga (When The Sun Sets), which altered the course of her life.

The film earned her an NAACP Image Award, a Student Academy Award Gold Medal, won the 2021 HBO Short Film Competition and was nominated for the 2021 Student Oppenheimer Memorial Trust Awards.

“They give a little bit of funding for postgraduate stuff. So, my thesis at that school ended up doing so well. It was just beyond my expectations especially because it was a story about my mom.

“And there was some scepticism among people at my school about whether it was the right thing to do because I wanted to shoot it at home. And they’re, like, ‘That counts as shooting an international film. You won’t have the safety net of the film school and everything. You’ll be going out almost like you’re on your own.’ So, I felt like I needed to fight for it.

Morare says her experience developing the film taught her about how to do independent filmmaking and, most importantly, how to stay true to stories that feel authentic to her.

“I was having to go out on my own outside of the safety net. And the pushback was people questioning why people would be interested in a foreign language film about a black woman in the 1980s.

“‘Why are you even doing a historic film? We’re tired of apartheid films,’ they said.

“One suggestion from someone at my school was that, instead of telling this story, why don’t I make it about Black Lives Matter or why don’t I tell a civil rights-era story?

“And I was just, like, ‘This is the story I want to tell. I’m trying to tell a family story. I’m not trying to tell a political story.’

“This is a story about my family. It’s about something that happened to my mom. It’s something that I feel is meaningful to me. It’s the kind of story that I want to see because, you know, Tony Morrison says, ‘Write about the things you want to see.’”

The filmmaker says another criticism she received was about the location.

“People at my school wanted me to shoot it in California. And they’re, like, ‘You can just treat California, LA, for Joburg.’ I’m, like, ‘No, I can’t because South Africans have a specific look and, if I shoot it here, there are high chances I’ll have to make it in English, because how many South African language speakers am I going to find here?’

“So, I guess it taught me to trust myself and tell stories that are true to me, not like what I think other people want to see.”

The film, which took her six months to develop, was shortlisted for the 2022 Oscars and was acquired by WarnerMedia OneFifty. It is currently streaming on HBO Max.

“I was overwhelmed. Yeah, it just felt wild, like beyond my wildest expectations. I was in awe as well, because I just felt like it was my maker who enabled this to happen, you know?”

Morare says when she told her mom she wanted to develop a film based on her life, she thought it was sweet, but didn’t really think about it until it was an actual film.

“I asked her, ‘How do you feel now that everyone knows that this is about you?’ And she’s, like, ‘No, I feel shy — but I also feel so proud and honoured.’”

Morare’s latest offering Why The Cattle Wait, which took her two years to develop, showcased at a private screening at the restaurant Artistry in Sandton.

During the Q&A session with South African actress and filmmaker Mmabatho Montsho, Morare spoke about the impetus behind the film.

“The story is actually inspired by some of my readings of Credo Mutwa’s folktales. I really loved the character he had of this mother goddess who had this turbulent relationship with her creation and with humans and that fascinated me.

“At the time, I was also really interested in folklore in general.”

“I remember seeing these beautiful images captured by a photographer called Christopher Rimmer of these cattle on a beach in the Eastern Cape.

“And the way he captured them, they just looked very god-like in a way. And, at the same time, almost human. And I was just, like, ‘Oh I wonder, because also cattle have a spiritual and cultural significance in Nguni culture.’

I was just thinking a lot about them. I thought, ‘I wonder if there’s a reason they go there, you know? And how cool it would be if they were waiting for someone?’

“And that’s kind of where that started and it merged with the Credo Mutwa stuff. At the time, I had wanted to write a love story.”

The film explores several themes, which include love and colonialism. Morare explains how she was able to weave the themes together.

“I’m interested in social issues already, so they just find their way into my work.

“With this story, the colonialism aspect, I thought, ‘If a god loves a human, and the human doesn’t want to return their love, what are the consequences of her abandoning her godly mission?’ And so, I thought, ‘Maybe she just lets the world burn.’”

Morare says she’d been thinking a lot about the aspects of South African cultures that were lost when colonisers first arrived on their boats in 1652.

Because of her religious background, she often thinks about ideas of deities, God and his relationship with humans.

The filmmaker says she always wants hers to be intimate human stories.

“That’s why the social issue is in the background, because it’s something I care about, but the main story is the intimate story.”

Speaking to the Mail & Guardian, Montsho said the film was exquisite.

“You can see a lot of preparation went into it. The quality is impeccable and she obviously has something to say, and she knows how to say it. I enjoyed that about the film.

“It’s thematically layered. There’s a lot of conversations you can have around it. Especially, for me anyway, from a religious point of view, like, did our God, in the context of the story, give up on us? You know, those kinds of questions.

“I think she’s brilliantly talented. She’s a master of her kind of storytelling.

Why The Cattle Wait was recently chosen to open the Africa Rising International Film Festival in Johannesburg.

Morare says there’s something she hopes viewers will take away from the film: “For me personally, it’s for people to have a feeling like they sat around a fire listening to like a grandmother telling a folklore story. Yeah, it’s just like that feeling.”