“So if you can overcome the personal fear for death, which is a highly irrational thing, then you’re on your way.” — Steve Biko, I Write What I Like (1978)

About 10 months ago, I authored a feature for Bubblegum Club on Siyabonga Mtshali, founder and lead designer of Siyababa Atelier. Tracing his practice from childhood to the inception of a fashion line, the crackly conversation uncovered how Mtshali’s unapologetic queerness and multidisciplinary approach propelled him beyond the confines of a conventional company. It became a movement and a fresh form of activism, centring local queer identity through an unfiltered lexicon of pleasure, luxury, defiance and radical self-fashioning.

Surreally, this trajectory now yields Siyazila — “We Are Grieving”. Launched in Cape Town at SA Menswear Week 2025, the somewhat unsettling collection embodies Mtshali’s evolving vision, unfolding through garment, video, sound and performance.

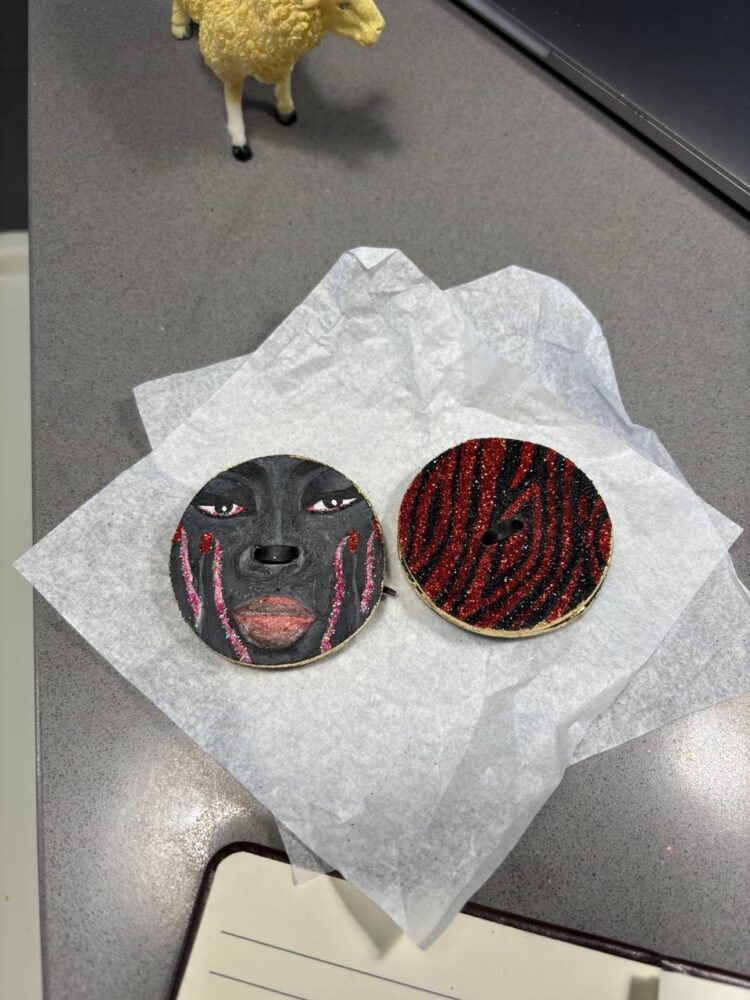

Visual artist Zandile Tshabalala collaborated on a custom piece that merges the brand’s emotive silhouettes with her painted figuration, while LIKKYLIKS translated the collection’s emotional register into an experimental soundscape. The project also features a video constellation directed by Retang Sebeka.

On the phone one time, Mtshali generously opened up about the collection’s connection to the death of his dear sister, Nontobeko Mtshali. One night, out at the practically deceased Smoking Kills Bar in Melville, Joburg, we shared libations — both in sadness and in bliss — playfully drowning our separate sorrows in the tenuous embrace of a barely breathing queer community.

At this moment, I even asked, intentionally, about Mtshali’s own fabulous fit. The designer’s retort was elusive, which I appreciated. I too was mantled in mountains of masking.

In these fleeting moments, grief becomes the ground upon which our sartorial expressions emerge. Pain shifts from shadow to style, sorrow to pattern, loss to luminous becoming. These sartorial synchronies invite a rethinking of ukuzila — not just mourning, but an ethical condition, a disciplined abstention from the familiar.

Expressed through clothing, ukuzila can materialise on the body as a negotiation between the visible and the invisible, the living and the ancestral. The mourning garment can become an archive — inscribed with love and relational obligation.

Ukuzila fashion then renders grief as necessarily performative — its fluid silhouettes, textures and colours do more than signal mourning; they activate a living circuit between the bereaved, the community and the ancestors.

The black of mourning, for instance, is not an absence but a saturated presence, thick with ancestral charge. In disrupting Western binaries of black and white, life and death, body and spirit, ukuzila reframes mourning as a stylised practice — one that honours the departed while sustaining the vitality of living through ritual and aesthetic pride.

Within African relational ontologies, where personhood is communal, processual and extends across temporal and spiritual registers, grief can never be solely personal. Mourning becomes a public and ritualised dialogue — an embodied choreography that facilitates a shared aesthetic and somatic practice. With the weight of this wisdom in mind, the collaborative nature of this project is not incidental but fundamental, echoing the si in Siyazila — a plural pronoun that affirms grief as a communal condition and an ontological assertion of togetherness.

Yet this togetherness doesn’t extend only to the living, but to the deceased, as well as inanimate objects — including clothing. Mourning is not merely a response to loss but a stylistic reverence toward the stunning and indiscriminate inevitability of death.

While the pain of loss is heightened during this period, so too is the fashionable exaltation of death as an unfathomable, yet fertile, passage. This layered immersion in mourning challenges reductive views of death as mere cessation, revealing instead its infinite potential as a source of beauty and becoming.

What Siyababa achieves with this project is a new step in an age-old process. Mtshali’s exercise in materialising his sister’s death demonstrates a command of the productive faculty of ukuzila.

When I asked if there was a particular piece that epitomises the project, he was definite — the brown sculpted mini dress, with its angular neckline and body-armour silhouette. The use of embossed leather and reptilian texture signals a hardened exterior, while the brass grommets punctuating the surface suggest openings — eyes for tears or mouths for wailing.

The carefully curated, yet somehow chaotic, cargo rope hangs with spectral weight off the dark model’s body — a relic of racial violence, yet a conduit for subversive, politicised play.

Entangled in the afterlives of colonial spectacle, the minstrel line, the lynching noose and the pirate’s defiance, it signals both domination and defiance. It stages not only redemption, but a sequence of survival — where beauty emerges from ruin and freedom is wrested. In this delectable dance of death, the future is neither pure nor promised, but fiercely, nihilistically alive.

This piece and its presentation reminds me of the Black is Beautiful movement. So hopeful. So fresh. Yet its restrained palette — richly attuned to dark skin — remains a carefully constructed casing, containing the volatile intensity of the flesh beneath.

The ensemble, while undeniably seductive, resists mainstream polish in favour of a more haunted aesthetic — one that acknowledges the relentless suffering entangled with black existence and how that very suffering paradoxically enables the experience of elite, even decadent and unknown, pleasures.

Siyazila by Siyababa Atelier, from this perspective, becomes a soft lens into ritual praxis where body, cloth and spirit coalesce — transforming grief into a giving force and mourning into a mode of becoming.

It carves out a liminal space in which memory, movement and material sustain ancestral presence and affirm blackness. As the studio navigates this period of mourning, it summons not only mortality but metamorphosis — a new aesthetic dawn shaped by pain, animated by continuity and grounded in the African principle of the oneness of all things.

Siyazila is on at the National Arts Festival until 6 July 2025.