The artist Senzeni Marasela

‘This is my way of saying that I know about your story. I see your daughters. I am listening.”

These words, quietly spoken yet dense with power, reverberated through a modest studio nestled inside Ellis House in Doornfontein. It wasn’t a formal gallery space that housed artist Senzeni Marasela’s latest work, but one steeped in red thread, memory, and repetition.

During this intimate performance lecture and studio session, the artist opened the door both literally and metaphorically into her decades-long meditation on land, displacement and the gendered experience of waiting, suffering and surviving.

This gathering is hosted under the banner Dialogues on Soil III: Walking with Theodorah – conceptualised and curated by Mpho Matsipa, Associate Professor at the Bartlett School of Architecture – and supported by the University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Studies, and the Graham Foundation.

Scholars, poets, and cultural practitioners – including Associate Professor and Director of JIAS Victoria Collis-Buthelezi and Stellenbosch University Senior Lecturer Uhuru Phalafala – came together to engage creatively through After Extraction, a pan-African cultural and intellectual gathering project combining art, research and indigenous environmental knowledge.

In this session with Marasela, at the centre, always, was Theodorah, a figure born of memory, stitching, trauma, silence and love.

“I’ve been performing Theodorah since 2003,” said Marasela. “My work as a multidisciplinary artist often begins in performance. It’s about dresses that reference my mother’s history, her silences and her pain.”

When Marasela speaks of her mother, it’s not with the removed reverence of a biographer but with the intimacy of a daughter who has inherited not only a name but an emotional archive. Theodorah, named after Marasela’s mother, is a constructed figure, yes, but she is no invention. She is the bridge between personal and collective memory, an avatar through which the artist traces her own lineage, while also stitching into history those who have been systematically erased.

“I started performing in the red dress,” she said, “because I needed to build monuments, not just to my mother, but to many black women whose stories would never have statues, plaques or public recognition.”

She made 38 red shweshwe dresses in total. The red was intentional. She handed some of the dresses to us in the audience and I was overcome.

Theodorah was my grandmother and my mother, to a certain extent. When my mother left for exile at the fragile age of thirteen, my grandmother’s life would change forever. She would suffer many heartaches that led to her having strokes, eventually going quiet and nonverbal for a very long time. Even when my mother returned. She tried talking because they had things to talk about, but that did not last long because they both harboured pain that manifested in anger. She went silent, again because pain held more space than forgiveness.

Many of her grandchildren have never heard her speak, till the last day of her life.

“Red is for pain, for memory, for trauma. But it’s also a colour that holds presence. It refuses to be overlooked. Like Theodorah.”

Marasela grew up in Vosloorus in the 1980s. Her stories of girlhood are flecked with images of being chased by dogs on the way to school, of dodging bullets in the township, of watching funerals pass by every day.

“One of my earliest memories,” she recalled, “was seeing my first dead body on the way to school in 1986. We didn’t have electricity or water for six months during the state of emergency. And almost every evening, young men were shot in our township.”

Marasela doesn’t romanticise this time. She narrates it slowly, deliberately, as if measuring each syllable against the enormity of what was lost. “There was trauma in the house and outside of it,” she said. “My mother was institutionalised in 1993 as she had schizophrenia. My father had to care for her himself. These silences, these breaks in memory, they became my material.”

She began stitching her narrative, literally, working with colonial domestic materials like Afrikaner doilies and turning them into sites of radical storytelling.

“As a child, we would walk past this old Afrikaner woman’s house. She was different, kind. She opened her veranda door and you’d see all these doilies on the couches. They were stitched with Afrikaans religious texts, meant to keep the household righteous.”

This memory became a foundational moment in Marasela’s practice: a discovery that objects, ordinary, soft and white, could hold ideological violence just as easily as warmth. “I started collecting them,” she said, “and transforming them. Stitching my stories into them.”

At the heart of her performance lecture is a quiet fury over how names disappear. How people, black men in the mines, women forced into silence, are reduced to generic labels. “If your name took too long to say,” she explained, “they told you not to give it.”

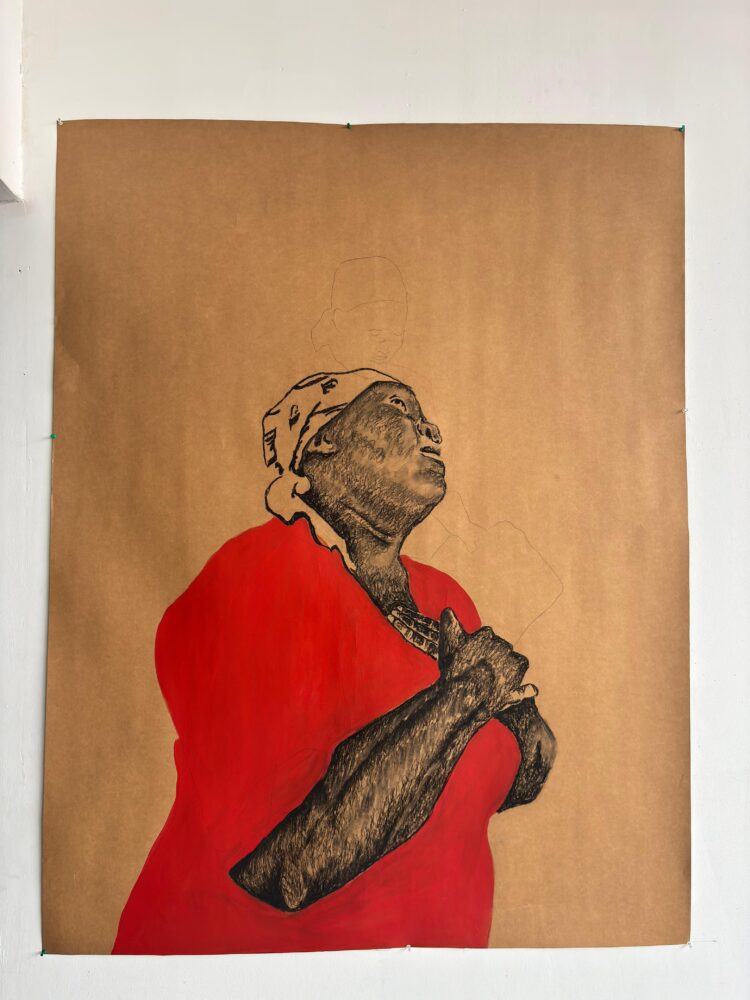

Being seen: The artist Senzeni Marasela with some works: itshali, a symbol of womanhood, provides its wearer with protection. Yet, beneath this layer of comfort is the weight of mining on women, and the monumental subterranean loss of life

Being seen: The artist Senzeni Marasela with some works: itshali, a symbol of womanhood, provides its wearer with protection. Yet, beneath this layer of comfort is the weight of mining on women, and the monumental subterranean loss of life

Her father, like many others, was given a name by the mine bosses. It wasn’t his. It was one that made him easier to control, to record and eventually to forget.

“There are boxes and boxes of mining records,” she said. “Most just say: ‘black male’. That’s it. No history. No family. No return ticket.”

This brutal archival silence became the seed for her drawings of mine shaft maps, lines originally made by engineers to mark where shafts needed to be closed due to excessive deaths. Marasela took those cold lines and stitched names into them, sometimes making them up, just to say: You existed. You mattered.

During her years of performance as Theodorah, Marasela wore the red dress into every part of her life: art exhibitions, family weddings, even nightclubs. “It was painful,” she admitted. “But necessary. I needed to be a monument.”

At one point, she encountered the Kulumani Support Group, an organisation for people affected by apartheid-era disappearances and violence. There, she met Dr Majozi Jacobs, who told her a story that changed her.

“There was a man,” she began, “whose wife had been arrested in 1978. The officers told her to remove her dress because it wouldn’t help her in prison. He never found her. Every time he came to a meeting, he carried that dress.”

He died in 2003, still holding onto that last piece of her. “That’s what these dresses mean,” Marasela said. “They’re not fabric. They’re evidence.”

At one of her cousins’ weddings, Marasela noticed something chilling. She wasn’t in any of the family photographs. “I was there,” she said, “but no one wanted to be photographed next to me in the red dress.”

So she began bringing her own camera. “I bought a tripod. I stood next to them and inserted myself into the story. Because otherwise, I would’ve been erased.”

That decision to claim space is central to her practice. In 2016, she was performing in Venice. “I drew a chalk line on the ground,” she said. “A border. A space where I could feel safe.” But children and tourists stepped over it. “Even when I created my own space, people invaded it.”

She faced similar experiences at JFK Airport in New York, where she was interrogated for four hours. “It’s hard to move through the world in this body,” she said. “To be seen as poor, alien, dangerous, just because of how I look.”

Marasela has now made 64 garments. Each one is a continuation of Theodorah’s story. Each one repeats the memory.

“There are women who still attend hearings at the Constitutional Court, still waiting for justice.”

The state has moved on. But people are still searching. “I want my work to be a place where they are remembered. A place that says: I see you.”

This intimate performance lecture, part storytelling, part ritual, was not a conventional art talk. It was a reckoning. With history. With archives. With the body.

Through Theodorah, Marasela has created a space where personal and collective histories of migration, erasure and survival are stitched across time. Theodorah is the monument that never got built. The archive that lives in red thread. The mother, the daughter, the witness.

“I carry her name,” Marasela said. “Because she couldn’t speak. She still doesn’t speak. Many black women couldn’t speak. So I speak.”