What does it mean to truly take your time? Artist shows us through a devotion to detail that transforms everyday materials into meditations on life, loss and transformation

Stepping into Walter Oltmann’s living room feels less like entering a domestic space than crossing the threshold into a quiet laboratory of time.

Not the cold precision of a scientist’s lab but something closer to an alchemist’s den — where patience is transmuted into art and wire becomes the language of memory.

Navigating between clusters of coiled metal strewn across the floor, I pass a man attending to the house’s electricity, who gestures towards Oltmann and says, in jest, “All he does is sit in front of the TV, watching the news, working that wire.”

And indeed, there he sits — Oltmann, with fingertips hardened in silver residue — at ease, entangled in a kind of temporal ritual. Around him, wire sprawls like quiet potential yet, along the walls hang the finished testaments to this devotion — intricate works wrought from stillness, and on a small table, a copy of his monograph In Time.

In this modest Kensington, Joburg living room, time itself seems to coil, loop and settle — proof that something enduring will emerge from meditative modes of making.

Scrutinising an artist’s practice has a lot to do with understanding their origins. “I grew up in Nongoma and studied fine art in Pietermaritzburg.

“We had a very dynamic fine art department in Pietermaritzburg. I had a good general grounding course — learning a range of disciplines and techniques. But, already in my second year, my lecturers saw that I had a particular feeling for sculpture. So that’s where it began.

“I had a lecturer, Willem Strydom, who worked mostly in metal and stone. He had trained in Britain, and I was impressed with the way he worked,” he says.

Oltmann would later follow Strydom to Wits to pursue his master’s degree. It was there that his practice began to shift — he recalls trips to scrapyards alongside Strydom, who sourced materials for his metal robust sculptures.

Oltmann, constrained by cost, gravitated instead toward wire, a material that was not only affordable but forgiving.

“A piece of wire goes a long way,” he says with a slight grin.

His first explorations with wire as a pliable medium for sculpture began in response to wire gabion structures encountered in the industrial Johannesburg terrain.

From adapting such gabion forms in his student works, he has gone on to explore his medium of wire more directly to arrive at forms that often express softness and stillness, perhaps aptly so, as he comments: “I work silently, alone.”

Like many dedicated artists, Oltmann went on to become a lecturer. “I spent many years, from 1989 to 2016, teaching at Wits.”

Held in major collections such as the Iziko South African National Gallery, the Norval Foundation and the Seattle Art Museum in the US, his intricate, time-saturated sculptures remain anchored by wire, speaking to a lifelong engagement with this deceptively modest material.

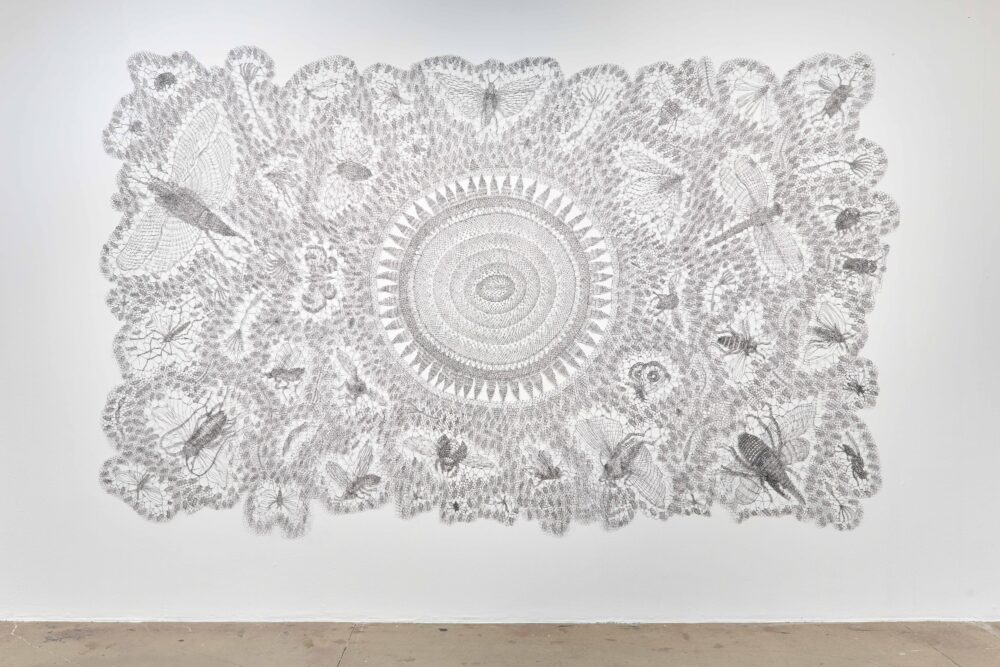

Walter Oltmann’s 2020 work Spread is made from aluminium wire.

Walter Oltmann’s 2020 work Spread is made from aluminium wire.

“Of course, I look a lot online, I look a lot in books and so on, and that becomes influential in what I do.

“I became interested in wire as a material in Africa and did some research during one of my sabbaticals. I discovered it was an incredible medium close to home.

“It was very difficult to make a piece of wire by hand — it takes a long time to draw a piece of wire, especially the thinner it gets. So, it was like an item of prestige and currency. That really sparked my interest and, yeah, it just never stopped.”

Oltmann’s exoskeletal structures depicting somewhat fanciful creatures — caterpillars, locusts, moths, crustaceans, reptiles — explore themes of metamorphosis and the balance between fragility and hardness.

In his Armour and Lace series, the delicate yet tensile wire mimics familiar suits or shells — both shield and surface — inviting reflection on form, corporeality and the porous boundaries between interior and exterior.

I ask about the act of making. Oltmann’s meticulous, repetitive techniques involve a form of 3D drawing in space by way of coiling, weaving and knotting of wire — processes that are meditative yet generative, allowing form to emerge slowly through time and labour.

This durational rhythm, rooted in ancient craft traditions, often dismissed, but rich in structure and meaning, defines his intimately intense practice.

Time — its repetition, rupture and sedimentation — threads through Oltmann’s work like wire through mesh. His sculptures evoke carapaces and exoskeletons and sometimes even depict bones and excavated relics associated with deep time.

Motifs ranging from the silverfish (fish moth) — a small but destructive insect — to the coelacanth — a prehistoric fish discovered off South Africa’s coast — symbolise hidden life and explore marginal creatures in suspended existence.

These inquiries, central to his PhD research, infuse his practice with a sense of personal archaeology and temporal layering.

This focus on the passage of time is reflected even after his objects leave his home studio. To my chagrin, he reveals that the pieces that make up his Silverfish sculpture lie in storage at the Johannesburg Art Gallery.

“I know it’s in the dark, in the basement, but that feels oddly fitting,” he says with a dry chuckle.

The artist’s 2021 work Carapax (Zygen)

The artist’s 2021 work Carapax (Zygen)

Oltmann’s book In Time was launched on 6 July. It followed his 2022 Claire & Edoardo Villa Will Trust Extraordinary Award for Sculpture, which supported the creation and exhibition of a major body of work at the Villa-Legodi workshop at the Nirox Sculpture Park.

Curated by Sven Christian, In Time weaves together interviews, essays and images that reflect Oltmann’s layered practice. Contributors include Brenda Schmahmann and Ashraf Jamal.

Though Oltmann has long been embraced in the upper echelons of the art world, what provokes the viewer is not his status but the quiet, unsettling edge to his work — a tension that feels both creepy and compelling.

His work places the hand at the centre of thought, using wire to draw in space through steady, tactile processes. He resists the urge for immediate spectacle, instead asking for a slower kind of attention — an insistence that meaning is not found only in the finished form but also in and through the act of making.

His work was featured in To Protect These Fragile Things, a group exhibition at the Goodman Gallery, Cape Town, which ran from 24 April to 26 June.