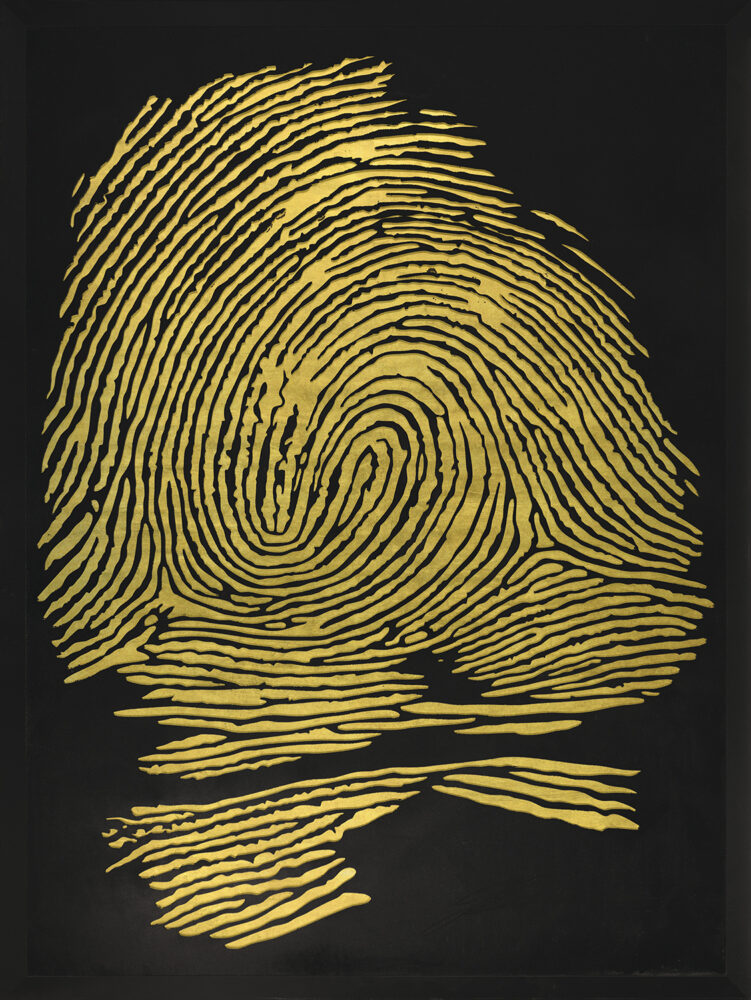

All that glitters: Artist Johnathan Schultz’s most distinctive and dominant medium is gold. Photo: Sonder Rose Media

Encountering Johnathan Schultz’s name, an English-speaking reader will immediately notice the odd presence of the letter “h”. Two names have been slammed together to make one — the “h” reads as a typo. Or, it assumes a character all its own.

This is one small way in which the artist stands apart, at odds, subtly aberrant. Can one perhaps interpret the artist’s nature thereby? Is he someone preoccupied with novelty?

Certainly, the American pop glitterati with which he has surrounded himself plays its part, but Schultz is less and less drawn to showbiz.

Perhaps because he wishes to be taken more seriously? Because pop art needn’t possess the noise one associates with Warhol, Koons and Murakami? Because the ironic or the atomic needn’t define an artwork? Because expression needn’t be a statement? These are triggered speculations. Artists change — or at least they should, if they wish to resist becoming a brand.

Schultz is pivoting. The typo is becoming far more interesting than the type. The artist, having confronted the paradox between compassion and excess, love and the superfluous, heart and bling, seeks to reconfigure the relationship between expression and his most distinctive and dominant medium: gold.

The title of his newest exhibition, Lasting Impressions: Tracing Identity & Resilience, is telling.

Against the fleeting, Schultz seeks endurance. Against exile and drift, he seeks empowered connection. Place is everything, be it physical or imaginary. Indeed, both are vital components for a vision founded on legacy.

Two sharply contrasting works sum up the artist’s shapeshift. The one depicts two swings rendered in earthy tones. They are positioned to the far left of the picture plane, subtly off-kilter, veering off the artwork.

Midas touch: Jonathan Schultz’s 2021 work Lasting Impression, using Nelson Mandela’s fingerprint.

Midas touch: Jonathan Schultz’s 2021 work Lasting Impression, using Nelson Mandela’s fingerprint.

The remainder is a colour-field of gold. Gustav Klimt doubtlessly comes to the minds of many when one considers Schultz’s love of incandescent and reverberative shimmer.

In Klimt’s case, it is gold paint that mattered; in Schultz’s, it is the precious metal. If Klimt constructs and intricately mosaics an ode to passion, Schultz focuses, non-descriptively, quietly, on a relatively uncompelling scene: two swings, wooden planks and chains.

Why? What must we intuit? The absent-presence of two companions? The power of objects in our lives? Our inseparability from things? A memory of play? The solemnity of its absence?

As for the field of gold? Certainly, this is the artwork’s magnetic core?

Sensationalism has typically been affixed to Schultz’s love of gold. It is a symbol of wealth, no matter the irrationality of its commodification.

As Warren Buffett wryly remarked, “Gold gets dug out of the ground in Africa, or someplace. Then we melt it down, dig another hole, bury it again and pay people to stand around guarding it. It has no utility. Anyone watching from Mars would be scratching their head.”

The absurdity is impossible to ignore. But then, it is absurdity which defines us. Certainly, it defines the art world, where we stand guard before commodities, the value of which is as rigged as it is intangible.

No matter. Pricing is merely an aspect of the immense complexity we call human expression.

Returning to Schultz’s artwork of paired swings shunted to the side, his field of gold, it is what is not stated, what remains unsaid, that possesses the greater traction.

Memory: Schultz’s View of Forgotten Times done in acrylic and mixed media on canvas.

Memory: Schultz’s View of Forgotten Times done in acrylic and mixed media on canvas.

For this is an achingly tender artwork, one that is tethered to memory and longing. As for the field of gold? It is doubtless a vision of Africa, the artist’s continent of birth, his most defining sense of place and being.

Here, gold is not merely an extracted commodity; it speaks to a magicked world, one that is not only understood through proof but through dream. For Africa is Schultz’s all-too-real and fantastical souce of inspiration. It is at this vital intersection that Schultz expresses his being, his self-knowing, his unquantifiable value as a diasporic African.

His perhaps most-talked about artwork, inspired by Nelson Mandela’s fingerprint — and, as such, by juridical record, apartheid, racism and oppression and liberation — is not only informed by its political pedigree, the fact that Mandela remains one of the greatest leaders of the 20th and 21st centuries, but by an acutely tender understanding of what it means to be human.

We know fingerprints to be unique. As such, we are never bonded to type, can never be known solely under the rubric of a raced or gendered group. As Kurt Cobain memorably reminded us: “All alone is all we are.”

Our singularity is the source of our profundity. Mandela’s fingerprint reminds us that we each walk alone, despite the desire on the part of autocratic regimes to reconceive us as part of a herd.

George Orwell witheringly told us of the great danger of groupthink. Sameness is designed. For Schultz, however, it is the anomalous and rare that matter far more.

His vision of resilience, while collectively and democratically understood, nevertheless enshrines the singular. That democracy is under threat worldwide — certainly in the US and in Europe — reaffirms the urgency of Schultz’s messaging.

As composer and impresario Leonard Bernstein remarked, “Art can’t change events but it can change people who can change events.”

This is the instinctive conviction that informs Schultz’s art, certainly its current shapeshift. In a global era in which identity is both inflated and toxic, Schultz asks us to reconsider human value. Introspection is vital for survival.

“Where society is at … worldwide, there’s this real need for the themes of identity, resilience … forging our own path forwards [now that] there’s been a breakdown in society.”

Schultz’s deceptive aesthetic, which owes much to pop art, to showbiz and glamour, now reveals itself, perhaps, to have always possessed a more generously empathic vision.

For the artist, Mandela is not a trope, a big name onto which to hang a work, but the embodiment of our salvation as a species and global civilisation.

Dr Ashraf Jamal is a Johannesburg-based academic, writer and cultural theorist.