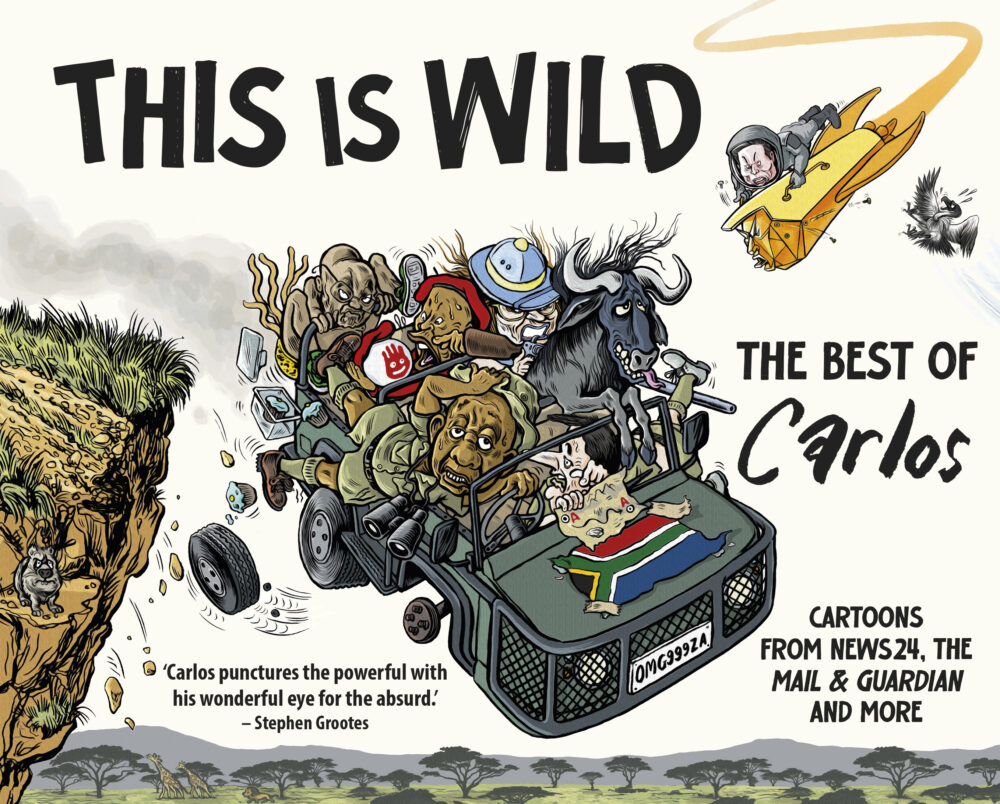

In line: M&G Cartoonist Carlos Amato recently published his first book-length collection titled This is Wild. Photo: Supplied

Carlos Amato’s career as a cartoonist began, as he puts it, with a “lucky pitch”. After a decade in the newsroom as an editor and writer, Amato was burnt out and doodling his way through meetings when an unexpected opportunity came along.

A vacancy opened at the Mail & Guardian after the legendary Zapiro moved on.

“I happened to draw a decent cartoon for my pitch,” he recalls with a laugh and, just like that, his next adventure began.

Eight years later, Amato has built a name for himself as one of South Africa’s sharpest visual satirists, his cartoons being published in the Mail & Guardian, News24 and now in his first book collection, This is Wild.

The collection spans a chaotic period in South African life — state capture, load-shedding, populism, pandemics — with Amato’s wry, painterly eye cutting through it all.

His work is both critical and compassionate, capable of skewering power while still finding humour in the absurdity of everyday politics.

I caught up with Amato to talk about his evolution from journalist to cartoonist, the delicate art of satire and what he calls “the reigning brands of madness” at the moment.

How has your background as a journalist shaped the way you approach visual satire?

It helps a lot. Cartooning requires a kind of writing. You have to condense complex issues into a single moment. It’s journalism, just in a different grammar.

The fewer words, the better, which took me a while to grasp. When I manage to do a cartoon with no words at all, I feel good about it, but it’s tricky. You can lose clarity.

You also learn that symbols don’t mean the same thing to everyone. I’ll reference a song from the Eighties or a movie from the Nineties and realise most of my audience doesn’t get it.

So, it’s a constant balancing act, finding that sweet spot where the idea lands for as many people as possible.

Does local political cartooning have its own distinctive DNA compared to, say, the US or Europe?

I think it’s quite varied. We’ve got younger cartoonists experimenting with meme language, comic-book aesthetics, Marvel-style exaggeration; it’s exciting. What really sets us apart, though, is that we’re still relatively free.

In the US, there’s been a serious contraction of space for political cartooning. A lot of cartoonists have been fired or pushed out of newspapers because editors are scared of offending readers, advertisers,or politicians. In Russia or China, you simply can’t be a political cartoonist unless you’re producing state propaganda — it’s too dangerous.

Here, we’re lucky. We can still push boundaries without fearing for our lives or livelihoods. You can draw the president, the opposition, religion and people might get angry, sure, but you’re not going to disappear.

Zapiro got threats from Zuma, of course, but for the rest of us, the space is still open. That freedom to mock power, to test the limits of what’s sayable, is precious. It’s one of the few areas where we’re genuinely ahead of much of the world.

Have you ever regretted a cartoon after how people reacted to it?

There was one about Winnie Mandela, when they renamed William Nicol Drive. I drew Winnie and Nelson in heaven and she’s furious that they got that boring road, saying she wanted the N1 from Joburg to Cape Town instead.

I honestly thought it was an affectionate joke, even a tribute, showing her as larger than life, someone who deserved more than a suburban traffic jam. But people read it as me mocking her and the backlash was brutal.

I was surprised by how angry people were. It made me realise how deeply South Africans feel about our heroes, especially someone as complex and revered as Winnie.

There’s a strong sensitivity around representing struggle icons and the dead and maybe rightly so. My intention was never to ridicule her; I was ridiculing the decision-makers, the bureaucratic smallness, the tokenistic way we sometimes honour people instead of engaging with their legacy.

So, no, I didn’t regret drawing it, but I did regret how poorly my intention came across.

Mostly, I only regret cartoons that fail to express what I wanted. I’m used to offending people: Elon Musk fans, MK Party fans, DA fans, EFF fans. Only ANC fans seem to ignore me!

You’ve said you don’t “speak truth to power” so much as “crystallise an opinion”. Is the idea of the cartoonist as a truth-teller outdated?

We sometimes articulate an aspect of the truth, but cartoons are seductive in that they simplify. There’s no room for nuance or counterargument.

You take a position and that’s it. The real value of cartoons is that they spark debate. The best ones get people arguing in the comments or over the office water cooler. We enrich the conversation; we don’t settle it.

What’s sad, in a way, is that cartoonists are a dying breed as paid journalists, partly because of this widespread belief that the media must be “neutral”, which is a joke.

Sure, reporting should try to be fair, but even hard reportage takes a position. There’s always an argument about what the truth is. Bias has always been part of the media.

That’s why good papers carry a range of opinions, so readers can weigh different perspectives. We cartoonists are part of that mix.

We’re not meant to echo anyone’s views or tell balanced stories. Our job is to enliven and enrich the debate.

You’ve written that cartoonists should “challenge whatever brand of madness is reigning”. So, what brand are we in right now?

Oh, there’s AI madness, there’s Zionist madness, there’s Trumpism madness, there’s xenophobic madness, there’s white genocide propaganda madness — quite a few to start with. And yeah, it’s a tough one.

Reporting or doing cartoons about someone like [KZN police commissioner Nhlanhla] Mkhwanazi is a challenge because it’s too soon to say whether he’s a kind of political entrepreneur trying to build a populist, anti-democratic, authoritarian platform, or if he’s a genuine democrat who’s taking on genuine corruption.

It’s too soon to know whether he’s truly committed to rehabilitating and preserving our policing system, or if he’s using that as a stepping stone to something else.

I’m still making up my mind about him. There’s no doubt that terrible things have been done and that the political elites and the police top brass are up to no good. But the question is: “What is he trying to do?”

That’s the kind of potential madness we have to guard against — when an outspoken truth-teller gets turned into a hero and people stop asking questions.

I’m also really alarmed by this growing perception that the media are “bought”. We’re broke, we can’t be bought. This is a labour of love.

What we’re trying to do is protect the public. And so much of what’s happened with the social media revolution has been about breaking that trust, deliberately.

These platforms want to keep people inside their echo chambers and they amplify voices that erode trust in the media because it suits them.

Impossible question — do you have a favourite from the collection?

Oh, it’s a tough one. I suppose the one that’s had the biggest reach is the cartoon about Thabo Bester getting a delivery from Temu of a Louis Vuitton prison uniform. It just struck a chord with a lot of people because he’s such a fascinating figure, comical but also scary.

To have him ridiculed seemed to touch a nerve, because he became a kind of figure for the lawless, psychopathic side of our criminal life. His fraudulence, his conviction that he’s innocent or a hero, all that prevailing madness inside his head. It’s surreal.

Quite a lot of people actually believe him, or if they don’t, they find him spectacular and aspirational.

I think people enjoyed that the cartoon was taking the mickey out of his fashion sense and self-pity. I put a lot of care into the setting: the uniform, the cell, the graffiti on the wall, all the details. I kind of put my all into it.

I post it once a year or so and it just flies. People love it. It’s probably the most successful cartoon I’ve done.

That’s a perfect example of how a single image can capture so many of the contradictions in a story like Thabo Bester that’s almost too wild to believe.

Exactly. That’s our job — to register the insanity of the world and make something enjoyable from it.

Not everyone will enjoy every cartoon — and that’s fine. You just keep drawing.

This is Wild by Carlos Amato is published by Jonathan Ball.