Shabby treatment: Community workers such as Mathapelo Kubheka have not been paid since June. (Paul Botes/M&G)

It is Sisanda Kulima’s birthday. Like for most other people, her 2020 birthday celebration is not what she expected it would be. But she hoped she would at least be able to bring a big cake to work to share with the other community health workers at Finetown Clinic, south of Johannesburg.

As one of Gauteng’s more than 8 000 community health workers, Kulima has been at the coalface of the province’s response to the pandemic.

These workers bring vital health services to the province’s underserved and densely populated townships. Many have carried on doing this important work, despite not being paid for months.

When lockdown was announced, Gauteng premier David Makhura stressed the critical role community health workers would play in the battle against Covid-19. He called them the “troops on the ground”.

Sisanda Kulima. (Paul Botes/M&G)

Sisanda Kulima. (Paul Botes/M&G)

The spokesperson for the Gauteng department of health, Kwara Kekana, said the department is working on using vacant posts to create permanent positions for community health workers. It is envisaged that all community health workers will be paid by the end of September, she said.

Kekana added that these workers “have always been important”. “They are anticipated to continue with the activities of health promotion and prevention. They should intensify their role in spreading the messages of lockdown regulations and other health-related information in communities.”

The Mail & Guardian first spoke with Kulima the week before the country went into lockdown in March. At the time, community health workers were still fighting to be made permanent employees by the Gauteng department of health. They finally attained permanent status at the beginning of July.

But a new struggle soon emerged: many of them have gone months without pay. Their insurance policies have lapsed, some face eviction and others have had to borrow money from loan sharks to get by.

Duduzile Makhubela. (Paul Botes/M&G)

Duduzile Makhubela. (Paul Botes/M&G)

“I thought this year we would be able to celebrate our victory after the things we have been through as community health workers,” Kulima says, sitting in the shade of the building she and her colleagues check in to every morning at 7am.

“We need laughter. But for me today, it is not a happy day. It is just a normal day where I am stressing.”

“But,” she adds, her voice suddenly sparkling again, “hopefully next year, it will be a nice birthday.”

After a five-year battle to be made permanent employees, Gauteng community health workers were buoyed by the announcement that delayed promises would finally be realised three months into the lockdown.

But without a salary to show for it, Duduzile Makhubela, a healthcare worker at Ennerdale Clinic, took leave to avoid the stress of going to work without a salary. Her anxiety has left her ill for a week, she says.

Makhubela says she is less worried about herself than she is about her colleagues, many of whom are their family’s only breadwinners.

As Makhubela speaks, her gold hoop earrings swaying, her daughter quietly works on her laptop at the nearby dining table. Makhubela’s oldest children bring in enough for them to get by, but she says: “I’ve got my needs. I’ve got my policies. I can’t just always rely on them.”

Makhubela says she often goes beyond the call of duty for her job, sometimes even using her car to ferry patients to and from the clinic and spending the whole day there with them on her days off.

“But now since I don’t get anything, even if they call me I have to say: ‘I don’t have money for petrol.’ They are my patients, but I can’t help them.”

Recognising the global attrition rates of community health workers, and the role they play in the provision of primary healthcare, the World Health Organisation published a set of guidelines in 2018 for countries to support them. The guidelines strongly recommended that policymakers ensure that community health workers are remunerated with “a financial package commensurate with the job demands, complexity, number of hours, training and roles that they undertake”.

Nonkululeko Mapikela pulls a crumpled letter from her bag, ironing it out with her hands. She sits next to her colleague, Mathapelo Kubekha, in a boardroom at the Stretford Clinic in Orange Farm. Outside the busy clinic’s gates, a line of patients makes the slow march towards the group of community health workers tasked with screening them for Covid-19.

The letter is meant to serve as proof to her landlord that she is employed by the Gauteng department of health and will be able to pay her rent when her pay cheque finally comes.

Mapikela questions how the health officials can sleep at night knowing that community health workers have not been paid since June. She and Kubekha say they are given the runaround whenever they ask.

Nonkululeko Mapikela. (Paul Botes/M&G)

Nonkululeko Mapikela. (Paul Botes/M&G)

“There are CHWs [community health workers] who have nothing. Our families depend on this money. I, myself, depend on this money,” she says, becoming agitated in her chair.

“So if it is like this, where should I go? Where must I run to? Who do I lay this complaint with? It is not fair.”

Kubekha shuts her eyes tightly when she talks. “I am not well at all,” she says.

“Honestly, 2020 hasn’t been my year … I wake up every morning, and I have to tell myself to be strong, get up and go to work. And I do exactly that. I wash my clothes. I make sure that I am clean, and I come to work. I have headaches every day.”

The silence in the boardroom is pierced by the sound of Mapikela’s ringing cellphone. She scrambles to muffle the dulcet tones of Lionel Richie’s Endless Love.

Mapikela became a community health worker after her brother became sick with tuberculosis. She wanted to understand the disease that was ailing him. Now she finds joy in helping the members of her community learn about how to take care of their health.

“It is nice to know you have made a change in people’s lives. You have made a difference. It is so nice when you go to people’s homes and, knowing that they had no hope, but just by seeing you things change. The way I love my job, I even call them my family,” she says before bowing her head. Her eyes glisten with tears.

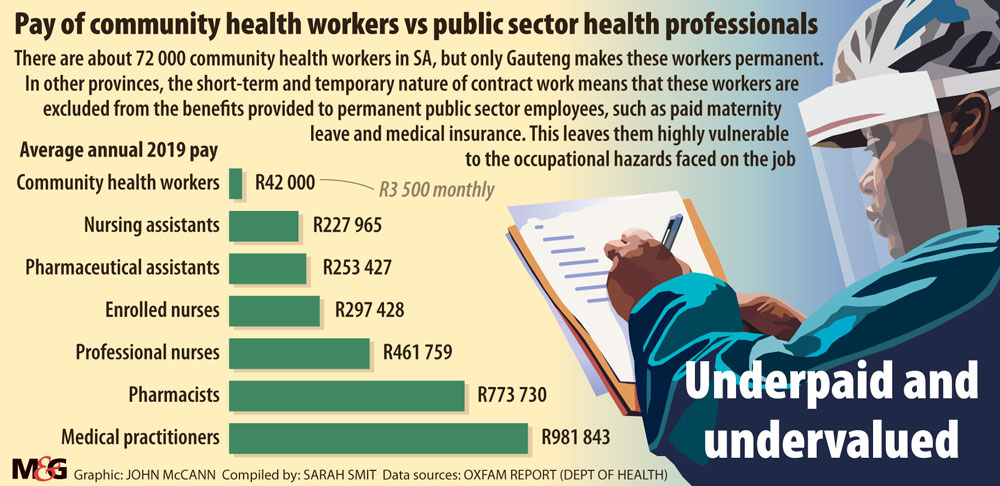

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)