Commissioner Kate O'Regan walks along with Vusi Pikoli during a site visit of the Khayelitsha SAPS. The Khayelitsha Commission of Inquiry embarked on several site visits around Khayelitsha on Tueday morning, stopping first at the Khayelitsha Police Station.

The civil rights group, Social Justice Coalition (SJC), has appealed to the national government and Western Cape provincial leadership to act on its Khayelitsha Commission of Inquiry to bring about police transformation in all informal communities across South Africa.

The Khayelitsha Commission of Inquiry investigated allegations of police inefficiency in Khayelitsha and a breakdown in relations between the community and police in the crime-riddled township outside Cape Town.

It was appointed by former Democratic Alliance leader and Western Cape premier Helen Zille in August 2012, in response to a complaint of inefficient policing in Khayelitsha, by a group of NPO’s including the SJC, the Treatment Action Campaign, Ndifuna Ukwazi, Equal Education and the Triangle Project.

Chaired by Justice Catherine O’Regan with advocate Vusumzi Pikoli as commissioner, the findings were concluded in an extensive 580-page report in August 2014.

The report unravelled the true state of crime together with its driving forces in the informal community. Community members, government officials and senior police officers appeared before the commission. In its essence, the commission wanted “to review and remedy the state of policing in Khayelitsha”, reads a statement.

In August 2014 the report was presented to Zille, and then police minister, Nkosinathi Nhleko.

However, seven years later the 20 recommendations made by the commission are left untouched and unchanged.

On Wednesday 25 August the SJC commemorated the report in a virtual event observing a “lack of initiative and implementation from the government — both national and provincial — which directly reflects the current state of crime and violence in Khayelitsha and neighbouring informal settlements”.

The current state of crime is reflected in the June to April quarterly crime statistics announced less than a week ago by Police Minister Bheke Cele.

Cele said the murder rate is up by 66.2% compared with 2020 and 6.7% if compared with the 2019 figure. In a period of three months a total of 5 760 people were killed nationwide with most of them in the Western Cape where Khayelitsha remains in the top 30 murder stations, said Cele.

Speaking at the commemoration, Ziyanda Stuurman, from the Abdul Latif Jameel poverty action lab (J-PAL) said: “National government was forced to really look in the mirror through this commission of inquiry, and forced to concede that they are failing the community of Khayelitsha. And in so doing, really admitting that they’re failing many, many other communities that look like Khayelitsha all across South Africa.”

Stuurman questioned the efficacy of commissions by recalling the Arms Procurement Commission (Seriti Commission), the Farlam Commission into the Marikana massacre and the ongoing State Capture Inquiry.

“Essentially, commission’s are incredibly powerful spaces, but they have deep, deep limitations. We know so much more about what happened at Marikana in those fateful days in August 2012. But we also understand that justice hasn’t been delivered to those who suffered at the Marikana massacre,” argued Stuurman, adding “and that really shows in very stark terms, what the limitations of commissions are.”

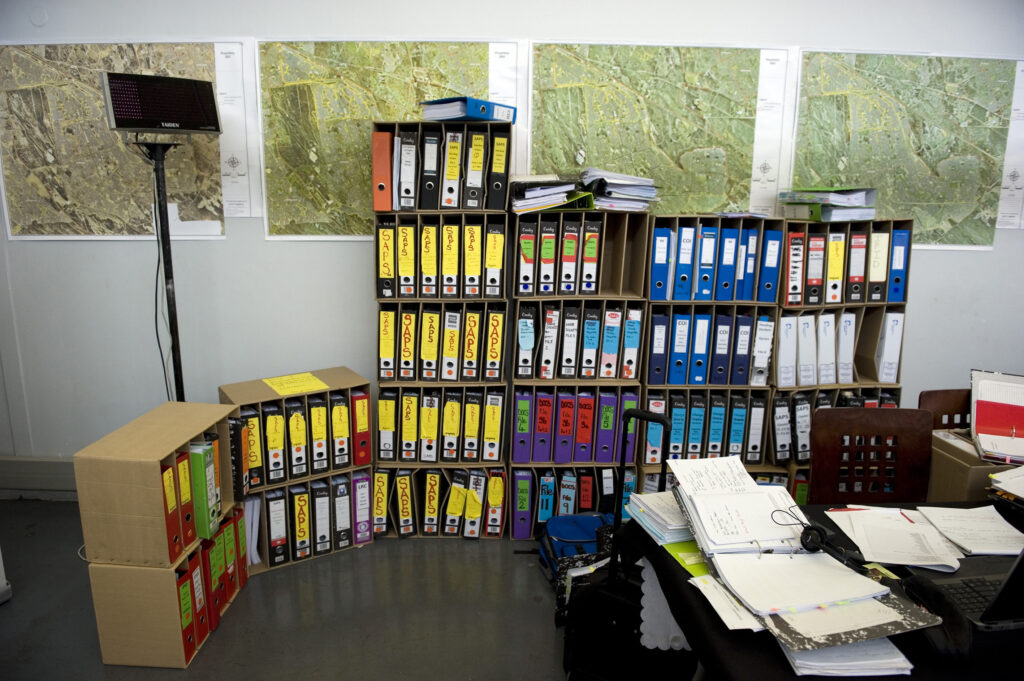

Commission file boxes during a break in testimony on Tuesday. The Khayelitsha Commission of Inquiry concluded it’s first phase on Tuesday this week with the testimony of Western Cape Police Commissioner General Arno Lamoer.

Commission file boxes during a break in testimony on Tuesday. The Khayelitsha Commission of Inquiry concluded it’s first phase on Tuesday this week with the testimony of Western Cape Police Commissioner General Arno Lamoer.

Highlighting one of the key issues raised by the commission of under-resourced police officers, Stuurman said the allocation of police resources at the time of the report “appears to be systematically biased against poor black communities… and the system is evidence of a failure of governance and oversight in every sphere of government.”

Nomzama Zondo, the executive director at the South African human rights organisation Socio-Economic Rights Institute, who was also speaking at the virtual commemoration event, said more police resources are needed.

“We need better servicing by the police. We don’t just want numbers but also quality. We need to get to a point where the culture of human rights is imbued in the police in such a way that those resources will start addressing peace and safety,” Zondo argued.

An argument emphasised by several guest speakers was that of political forces ultimately limiting police transformation to create safer crime-free communities.

“One thing that has been missing and is clear from both commissions (Marikana and Khayelitsha) has been the political will. And we know that for as long as there’s no political will to change policing in this country, there is not much that can be done,” stressed Zondo.