Discriminatory laws: Masewa Joseph Netshituka with his first wife, Tshinakaho, (left) and his second wife, Masindi (right).

After decades of marriage, four children and toiling on a farm to build her husband into a businessman, Tshinakaho Netshituka was left with no rights over his property or assets when he died.

Tshinakaho was one of the five wives of Masewa Joseph Netshituka.

Her nephew, Maanda Alfred Netshituka, speaks of his memories of his aunt. “Theirs was a traditional love story which followed the Tshivenda saying, ‘Vhazwala vha ya zwalana’, loosely translated to ‘cousins birth each other’,” Maanda said.

Described as a gentle, kind and loving soul who was also hardworking, Tshinakaho, alongside the second wife, worked the land in Mauluma, growing mealies and peanuts.

“Tshinakaho and the second wife played a huge role in Joseph’s journey of becoming a businessman because they would give the produce to him to sell in Gauteng. Ultimately they uplifted Joseph to be a successful businessman,” Maanda said.

After the death of Tshinakaho’s husband in 2008 and finding out that she would not be getting anything from his legacy as their marriage was out of community of property because it happened before 1988, Tshinakaho’s health started deteriorating.

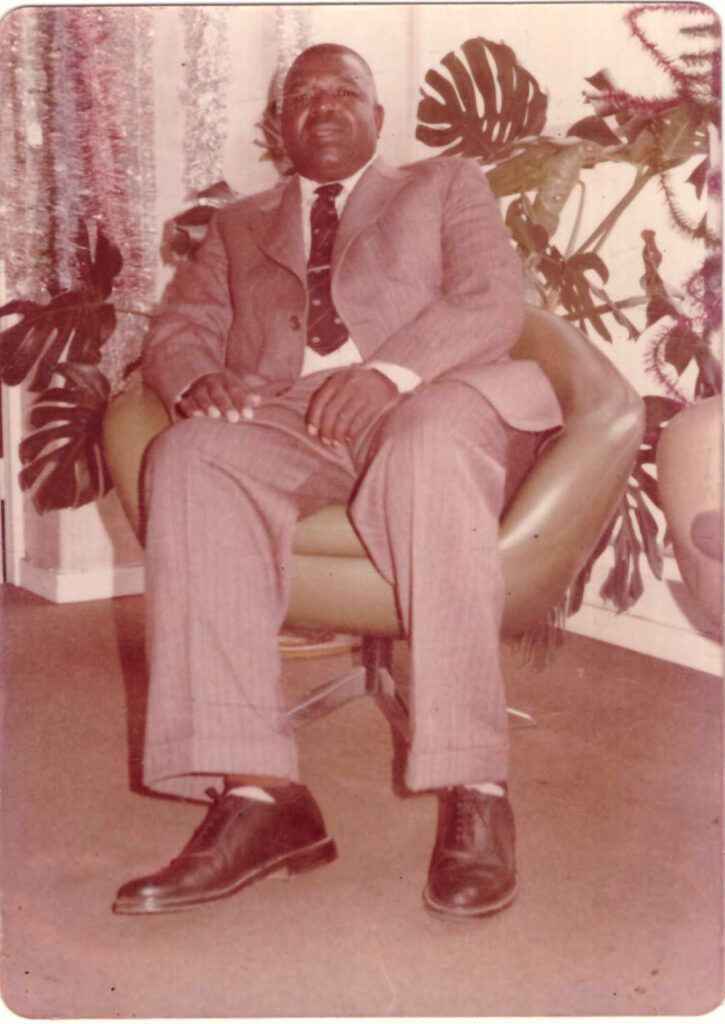

Joseph Netshituka during his days as a businessman.

Joseph Netshituka during his days as a businessman.

This was exacerbated by the family suddenly finding out about another marriage Joseph had entered into. The fifth wife, according to court papers, had been married in community of property and got a 50% stake of the estate. “That on its own took a huge toll on Tshinakaho’s health because she started suffering from depression, ultimately leading her to be diagnosed with high blood pressure and diabetes. She just became a former shadow of herself until she passed on,” said Maanda.

Tshinakaho died in 2011.

Her story is similar to other black women who entered into marriages, traditionally and legally under the apartheid regime. These marriages were discriminated against until a few months ago.

For more than a decade, four women fought against the inequality forced upon their marital unions. Tshinakaho’s daughter, Matodzi Ramuhovhi, has been part of the fight to give her mother’s marriage its rightful status.

After the death of her father, Joseph, the family was left with what they believed was an unfair distribution of his estate because their mother was not married in community of property under the apartheid laws.

The discrimination against black women’s marriages stretches back to 1927 when the Black Administration Act was legislated. Section 22(6) stated that these unions would be out of community of property unless they provided reasons they should not be. This meant that when a black woman was married, she could not own any of the assets or property accumulated while married.

In 1988 the Marriage and Matrimonial Property Law Amendment Act repealed section 22(6) of the Black Administration Act.

But the new law was also unconstitutional in that the laws governing marriages entered into before the amendments remained in place.

In April, the constitutional court handed down a judgment that found sections of the Matrimonial Property Act unconstitutional because it maintained and perpetuated the discrimination created by the Black Administration Act, which stated that the marriages of black people would automatically be out of community of property.

According to the Legal Resources Centre (LRC), the judgments obliges South Africa to confront the uncomfortable reality that even after 25 years into its constitutional democracy, black people are still subjected to remnants of oppressive and discriminatory apartheid laws.

Tshinakaho’s story is not uncommon.

On 29 May 1968, Elizabeth Gumede and her husband entered into a customary marriage. They lived in KwaZulu-Natal and were married for more than 40 years and had four children.

According to a 2008 constitutional court judgment, Elizabeth was not formally employed because her husband did not permit her to work. “However, by whatever means she could garner, she maintained the family household and was the primary caregiver to the children. She had no means to contribute towards the purchase of the common home; her husband, who was working, did. Mrs Gumede states that over time the family acquired two homes,” reads the judgment.

Elizabeth had approached the court after her husband decided to file for a divorce. It is here that she learned that she was married out of community of property. By this time, the couple had separated and she was living in Umlazi and her husband in Amanzimtoti.

He received a pension from his former employer and Elizabeth was on an older person’s grant and received occasional financial support from her children.

Elizabeth accepted that their marriage had broken down irreparably. Her husband wanted to sell the Umlazi house and split the proceeds. According to Elizabeth, her husband would have retained the rest of the estate yet she would receive about a quarter of the total value of the marital property.

Tshinakaho alongside her late granddaughter Pertunia Netshituka.

Tshinakaho alongside her late granddaughter Pertunia Netshituka.

The court ruled that parts of the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act 120 of 1998 were inconsistent with the Constitution and therefore invalid.

Elizabeth was married in community of property.

The LRC says it has, over the past 10 years, worked to protect women against eviction by their husband’s families on his death, or by the spouses themselves on dissolution of a marriage.

“Women’s role in building the family home should not be underestimated nor ignored as their contribution might not be financial, but they crucially serve as caregivers and help acquire, build, and maintain family homes alongside their husbands,” the LRC said.

“Under traditional customary law in South Africa, a woman remained under her family’s guardianship until she married and upon such time, the duty would fall on her husband. This made women invisible in front of the legal system, by relegating her to being a perpetual minor and therefore nullifying any claim she has to her rights.”

The latest case was that of 73-year-old Agnes Sithole whose marriage that was still governed by the Black Administration Act. According to the heads of arguments filed by the LRC, Sithole and her husband married on 16 December 1972.

She told the court that at the time, the officiating priest advised them that marriage out of community of property was the only option available to them as black people. They knew no better and did not seek legal advice.

Between 1972 and 1985, Agnes stayed at home and raised the couple’s four children. She also ran a home-based business selling clothing. Her husband was employed as a project manager at an engineering firm.

All of Agnes’s income was used to pay for their children’s education in private schools and for family and household expenses. Her contributions to the family and its costs led directly and indirectly to the increase in her husband’s estate value.

In 2000, after the couple bought a family home registered in the husband’s name, their relationship deteriorated.

According to the LRC’s papers: “He engaged in extra-marital affairs and threatened to sell the family home without her consent. In 2018 she brought proceedings in the Pinetown magistrate’s court for a domestic violence interdict.

For the first time, she then learned that she was married out of community of property and not in community of property as she had believed. She learned that her husband could carry out his threat to sell their family home without her consent.”

The court found no reasons to delay and perpetuate the unjustified unequal treatment of black couples. Agnes’s divorce could continue with the understanding that she was married in community of property and had the same property rights as her husband.

But, for some families, the fight has not ended.

When Joseph died in 2008, he left behind wives and children. Tshinakaho’s daughter, Matodzi, witnessed how hard her mother worked to build the fathers estate. But she was left with nothing.

After the landmark judgments, not much has changed for Matodzi. The rulings did not deal with the issue of how the law should be applied to the children of a customary marriage, which was once deemed out of community of property, especially in the case of polygamous marriages.

According to Matodzi’s cousin, Maanda, “She doesn’t even have the strength to talk about the entire issue because it pains her and she becomes overwhelmed with emotions.”

Though the constitutional court finally granted the deceased her rights to marital property, it is still not clear how much the deceased’s entire estate — including land with a shopping centre, a restaurant, a bottle store, driving school and some house stands in and around Thohoyandou — should be divided.

“It has been a long journey even though Tshinakaho is no longer alive to witness. Honestly we do not wish that other families get to walk the journey that we walked. Due to the constitutional court’s decision, they should be relieved that we walked the journey for them.

“And if ever there was something that is not done accordingly in a family, this is the time for them to rectify the wrongs and do the right thing so that those meant to enjoy what is theirs can do so,” Maanda said.

This article was possible through the support of the German federal foreign office and the Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen (IFA) Zivik funding programme. The views presented in this article do not necessarily represent the views of the German federal foreign office or the IFA