South Africa does not even have 60 child and adolescent psychiatry specialists and only 20 are in the public sector. (Illustrations: John McCann)

South Africa’s child and adolescent mental health services are in crisis, with only one in 10 children with diagnosable mental disorders able to receive treatment.

This is according to the Children’s Institute at the University of Cape Town (UCT), in its latest annual Child Gauge report, which reviews the condition of children in the country. The review highlights the status of child and adolescent mental health (CAMH).

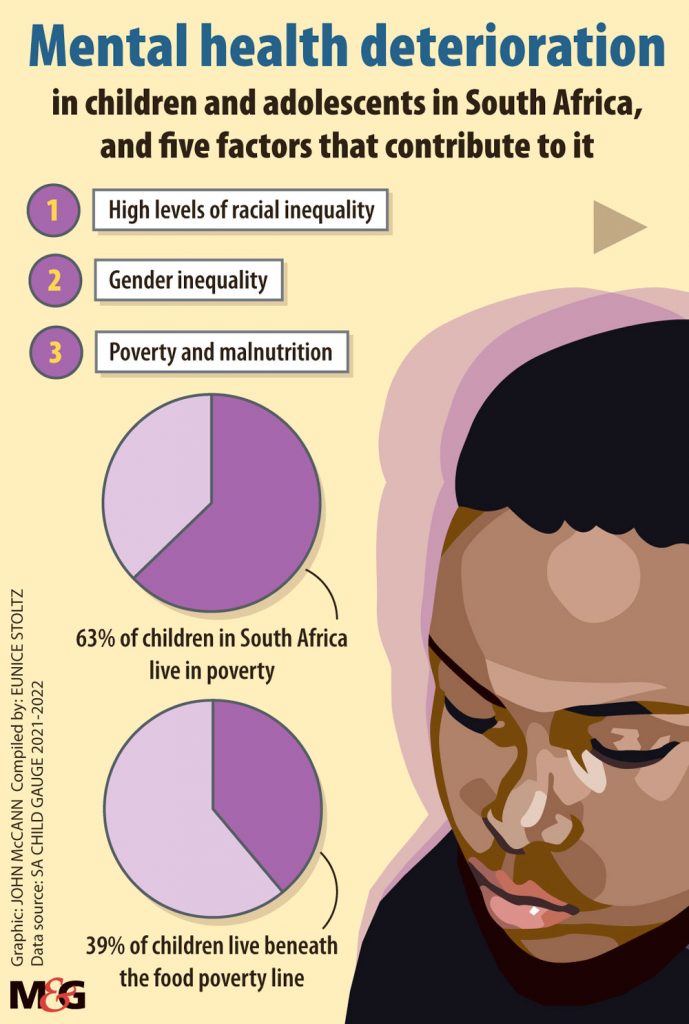

“Due to historical neglect and underinvestment in mental health, there are serious gaps in prevention and care for children and adolescents in South Africa,” Bongani Majola, chairperson of the South African Human Rights Commission, said during the launch of the publication.

“These gaps often lead to gross human rights violations that rob children and adolescents of their quality of life, and potential to build resilience,” he said.

Findings of the 2021-22 report suggest children and adolescents in need of treatment “are likely to encounter a health sector ill-equipped to give them the necessary care and support”.

Petrus de Vries, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at UCT, writes: “South Africa’s child and adolescent mental health services are in crisis. Child and adolescent psychiatrists and other mental health professionals are available in only a handful of urban centres; while limited services and human resources compromise care at district level.”

South Africa has fewer than 60 child and adolescent psychiatry specialists, but this is still more than any other country in sub-Saharan Africa.

Of these specialists, 20 practise in the public sector, while there are only five funded training posts nationally. Government-funded specialist services for children and adolescent mental health are available in Cape Town, Johannesburg, eThekwini and Tshwane, the report found.

Pointing out the essential role of primary health care clinics and district hospitals, Simphiwe Simelane, of the Centre for Autism Research at UCT, states that these medical institutions “should be able to identify and care for children close to home while being supervised by child and adolescent mental health specialists caring for children with more complex conditions at secondary and tertiary hospitals”.

The report highlights the strengths in the country’s child and adolescent mental health services and systems (CAMHSS), in that the mental health of these vulnerable groups has been a subject of discussion by the government and policymakers for more than two decades.

“Although not yet implemented, the policy guidelines on CAMHSS were developed in 2003, and the norms for South African CAMHSS were commissioned in 2004,” notes the report.

Further to this, the National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2013-2020 outlined the central role of district health services to strengthen general mental health services in South Africa. District mental health teams are meant to have oversight of district health services.

But the absence of detailed implementation plans for these teams resulted in only two functioning in 2019, according to the report. One is in the Free State and another in Mpumalanga.

“It is also vital that CAMH services are included in the National Health Insurance [NHI] baskets of care in order to uphold children’s rights to basic mental health care and financial risk protection,” said Simelane.

The national health insurance bill, currently under review, seeks to provide “inclusive health care” for all South Africans.

The report argues that although the bill states that all children will have access to basic health care services, it “does not define what will be included in the services”.

“This is particularly concerning because there are currently no CAMH-specific disorders on the chronic disease list or the minimum prescribed benefits in South Africa and these conditions may therefore be overlooked when the basic services are defined.”

Speaking at the launch of the report, Mark Tomlinson, of the Institute for Life Course Health Research at Stellenbosch University, noted: “Every single child in South Africa needs support so that they can develop the strength and resources to meet life’s challenges. And the ordinary support of parents, teachers and communities can help build resilience and set children on a positive trajectory.”

One of the report’s several recommendations is that investing in child and adolescent mental health services and systems now will provide the early interventions needed to prevent long-term, multi-level costs associated with poorly functioning services.

Tomlinson said: “Building children’s confidence and capacity to take initiative, cope with adversity and contribute to community life are critical ingredients of mental health and active citizenship … we need to work in partnership with young people and harness their energy, creativity and clarity of thought to design policies, services and programmes that are responsive to their needs and prepare them for the challenges to come.”