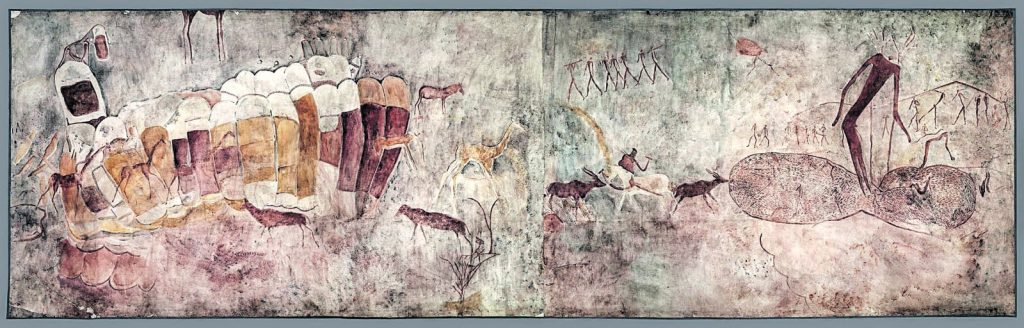

Viewing: Earlier this month, the Ha Baroana went on display in an exhibition of South African and international art at the National Gallery in Cape Town. Photo: Kevin Davie

Ha Baroana is a good place to think about one of the region’s greatest legacies — its rock art. To get there you travel east from Maseru in Lesotho towards Roma and then up the steep Lekhalo La Baroa (Bushman’s Nek Pass).

It is well signposted, so stay away from trusting Google, which took us along a non-existent path past a solitary horse and through a water-logged field. We then bounced along a sloshy track, which was too much even for the odd minibus taxi that operates here.

In the distance we could see the Ha Baroana Arts and Crafts Centre. It had not been visited by anyone in a car for yonks; there were no tyre tracks at all leading to it.

Comprising several thatched buildings, it felt abandoned. But a young man, Mahasa Mahasa, appeared, opened it up and gave us a quick tour, there being little to see besides a few calabashes and poor copies of paintings on the wall of one of the buildings.

We followed Mahasa down into the valley to the Liphiring River, full from months of rain, crossing two steel pedestrian bridges, and then down a slimy, rocky path through a dappled forest. A huge pinky-cream overhang rose up above us.

One rockwall was adorned with what had been paintings but now was little more than faint red-ochre, just visible in places.

The 1900 exhibition

But I knew what had been, because, nearly a century ago three artists had produced a monumental canvas, 10 metres long by 2.5 metres high, of what they had seen here.

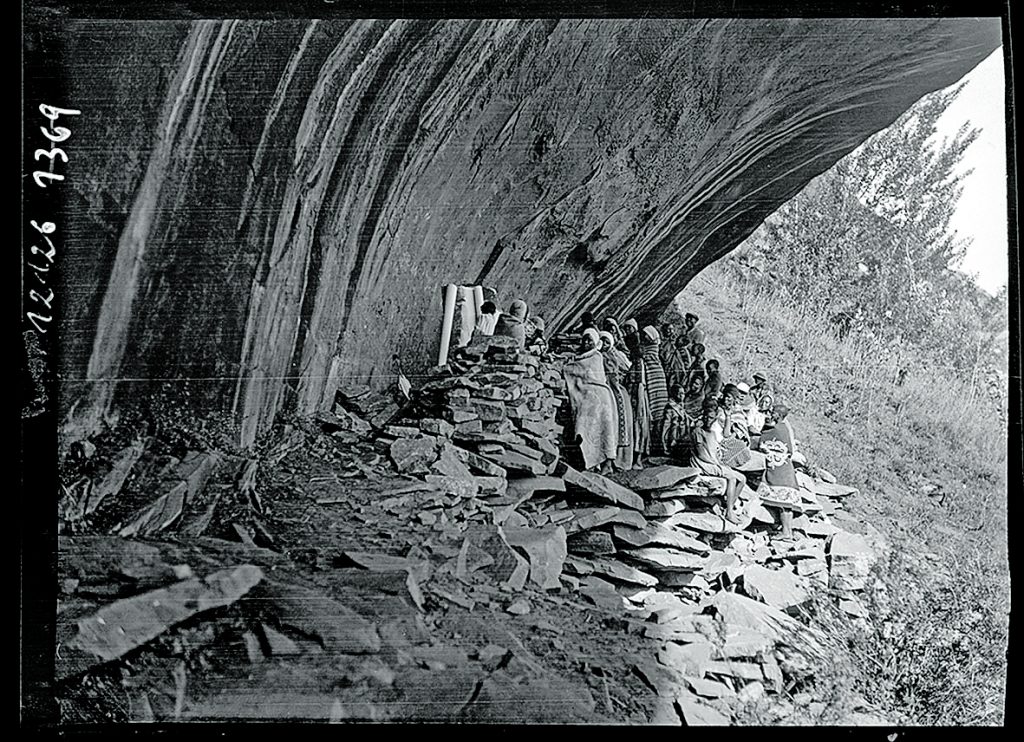

The artists, Elizabeth Mannsfeld, Maria Weyersberg and Agnes Schulz, had made this copy in 1928 at the beginning of a 20-month expedition. Led by German ethnologist Leo Frobenius, they made copies of more than 1 000 rock artworks in South Africa, Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Basutoland (Lesotho) and South West Africa (Namibia).

The copies were exhibited from 1930 to 1932 in Frankfurt, Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam and Zurich, and in 1937 in the United States, first at the Museum of Modern Art and then a subsequent tour of 37 cities.

The sites the artists visited are often out of the way and hard to find. Expedition members used rail, car, horse and foot, carrying ladders and art materials. Teams of oxen or donkeys in some cases pulled their vehicles across rivers and out of other tricky situations.

Surprisingly though, given its ambition and scale, the work of the expedition does not have much of a profile in South African rock art circles. But there are an impressive number of copies made, in watercolours and oils, on paper and canvas.

Frobenius’s Southern African tour, his ninth of 12 on the continent, criss-crossed much of the sub-continent. After not too many months the expedition ran out of money. Frobenius convinced the education minister, Daniel Francois Malan, to put up £5 000 in exchange for copies made by the team.

These copies, 479 to be exact, duly arrived early in November 1931, and were put into the care of the South African Museum, the forerunner of the Iziko Museum. The South African Museum dates back to 1825 and has been headquartered at the Company’s Garden in Cape Town since 1897.

Some of the material copied by the Germans was shown in Pretoria and Johannesburg in 1929, but the artworks bought by South Africa have never been shown in full. A limited selection was included in Made in Translation, an exhibition curated by art historian Pippa Skotnes and Petro Keene, which ran at Iziko for a year in 2010.

Most of the Iziko copies are on the South African Rock Art Directory website, as are 1 135 images on the website of the Frobenius Institute.

Likeness: Artist Maria Wyersberg’s copy made at the Enanke site in the Motopos. Photo: Courtesy Frobenius Institute

Likeness: Artist Maria Wyersberg’s copy made at the Enanke site in the Motopos. Photo: Courtesy Frobenius Institute

Inside the storeroom

But seeing a small image on the web does not begin to match the full-sized experience.

I asked Iziko for permission to see the collection, saying the work deserved a wider audience, especially as much of the country’s authentic rock art has badly deteriorated.

Iziko’s Wilhemina Seccona agreed to my spending three days with the archive, which had been in deep storage for the past six years while Iziko awaited its new premises to be completed.

Assistant Benjamin Marais, who has been with Iziko since 2015 but had never seen the collection, was looking forward to seeing it. He wheeled two out-sized cardboard boxes on a trolley along the corridor from a storeroom that houses rock art collections.

Iziko does not have a catalogue and there is no way of knowing which copies are stored in what boxes. The copies, carefully wrapped in a roll with generous amounts of acid-free paper, were stored in no particular order.

I was given special gloves and began with Box M, which had 11 drawings. I had agreed with Benjamin that I would call him over, interrupting his other work, if the image was particularly impressive. This was the case with virtually all of them, the vivid colours seemingly being released from entrapment as they were unrolled.

Carefully unwrapping and re-wrapping the works took time as did trying to figure out where the copy had been made and by whom. Some included the location, for instance, a farm, while others did not. By lunchtime, I had seen only 11 copies.

Earlier research had led me to a 2011 thesis on the expedition by archaeologist Petro Keene, parts of which I had read. Re-reading it over lunch at a cafe in the Company’s Garden, I saw it included a catalogue.

Keene highlighted one work, number one, the Ha Baroana (it means Place of the Bushmen in Sesotho), which is 10 metres long and 2.5 metres high. It was one of the first copies made by the expedition, and the largest, taking three months to complete.

The cardboard boxes I’d seen were large, say 2.5 metres long, but in no way could accommodate such a monumental work.

Unwrapping Ha Baroana

Back at Iziko I asked about it. It was in storage, although there was some uncertainty whether it was part of the Frobenius collection. Benjamin would show me the Ha Baroana the next day.

It is so large that when shipped to South Africa in 1931 it had its own box. It now resides rolled up on a top shelf in the rock art room with another, almost-as-large canvas alongside it. It was much too long for the room Iziko makes available to researchers. Benjamin and I had to unroll it in two, one section at a time, spread across a set of tables. On the back it had the names of the three women who created the copy. As Benjamin and I slowly rolled out the canvas, we were treated to colours so bright they could have been painted yesterday. There was an overall story of eland, some giant-sized, others in herds, and people, often in lines, elongated and close together, some superimposed on the animals. One small area had a sparkle of white crosses.

Preservation: Three women artists on the Frobenius expedition of 1928/9 spent three months at the Ha Baroana site in then Basutholand making a ten-metre long copy of the rock art. Photo: Courtesy Frobenius Institute

Preservation: Three women artists on the Frobenius expedition of 1928/9 spent three months at the Ha Baroana site in then Basutholand making a ten-metre long copy of the rock art. Photo: Courtesy Frobenius Institute

There were long leg-like images painted really close to one another, creating movement. Elsewhere, lines of small dashes in seemingly random spaces gave similar effect.

Parts of the canvas had little on it, others were layered and detailed, a celebration of line, shape, colour and form. The whole included a set of self-contained vignettes, masterpieces in their own right.

It was much too much to take in. As magnificent as the Didima Gorge is, and the art we’d seen there, there was a sense of incompleteness. This is often the case in viewing rock art in situ. This rendering of the Ha Baroana was a complete story.

Blown away

Keene, whose recent work includes curating an exhibition at the Origins Centre in Johannesburg and exhibiting her own artworks in Bergen, previously worked as collections manager at Iziko, where she spent four years with the archive and knows its contents better than anyone.

She came across the Frobenius copies at Iziko shortly after volunteering at the museum in 2006.

“A memorable day was when I noticed on the top shelf of thousands of boxes of archaeological finds, two extremely large rolled-up paintings. I fetched a ladder and as they were heavy, I needed assistance to get them down from the shelf.

“They were rolled out in a long passageway and I could not believe what I was seeing. One of these copies is from Ha Baroana.”

These magnificent large copies, she says, “certainly do blow the mind away. It was a great privilege to be working with these copies on a daily basis for a number of years.”

Skotnes echoes these sentiments. “The Frobenius collection is truly wonderful — the biggest ones are incredibly impressive. We were able to build a cabinet for the longest one [the Ha Baroana] which was shown in full [at Made in Translation].”

Shortly after Keene came across the Ha Baroana at Iziko, the copies housed in Germany at the Frobenius Institute, founded in 1925, were also being re-discovered.

Richard Kuba, who curates the rock art collection at the Institute, said “the copies were stored in the Institute until the early 1940s, when luckily they were temporarily transported outside of Frankfurt am Main as a precaution and thus survived the bombardment in March 1944, which destroyed the Institute.

“However, after the war, they were poorly stored in a damp basement of an old villa, which was the location of the Institute until 2001. Then,

they were moved to the less damp basement of the University of Goethe building, still forgotten until we unrolled them for the first time in 2007 for digitisation.”

Researchers who found the works were struck by how modern and fresh they appeared. “When we pulled them out, we were blown away,” said Kuba.

Mutoko

The large canvas that resides alongside the Ha Baroana was copied by the fourth artist on the expedition, Joachim Lutz. A 1929 photo shows Lutz perched halfway up a ladder, a giant canvas rigged up in front of him and a mighty elephant rising up on the rock wall behind him.

Seven metres long, it is known as the Mutoko, where it was copied, at a cave 140 kilometres east of Harare. Also extraordinary, it is quite different to the Ha Baroana, most of the background being a triumph of flowing colour, light browns, creams, pale yellow, off-greens and brilliant white.

The foreground includes black-and-white zebras, and to-ing and fro-ing people — mostly painted in red ochre — both small and large. There are trees and other flora, a feature of rock art north of the Limpopo River, which is largely absent in the south. Large bulbous connected pods spread across the whole, pulling it together. A double snake-like line divides much of the whole into two.

Like the Ha Baroana, you know you are looking at a single story, the multiple, layered images, all the elements, as contrasting and different as they are, somehow contributing to a synergistic whole.

But the Ha Baroana and Mutoko have lots of differences too. Eland overwhelmingly dominate the former; they are embedded and deeply layered into it. There are plenty of antelope in the Mutoko, but they are much more dispersed and differentiated, as are the people who dance, run, chase, cavort and frolic as individuals.

The human figures in the Ha Baroana are grouped, in lines, marching or moving in unison and in close proximity. In one case we see lots of long legs, multiple individuals with separate heads, but sharing a long common shoulder. The figures are partly transparent; you can see the eland through them. Most of the human figures have animal heads. In the case of the Mutoko the figures are fully human.

Benjamin and I discussed whether we preferred the Ha Baroana or the Mutoko. My sense would be to have them on opposite ends of a large gallery with a long bench facing each one, to sit, stare, and wonder.

I tried to compare my experience with previous monumental artworks I have seen. Two came to mind, the Sistine Chapel and Geurnica.

My preference would be both of these African works, a key difference being that the first two were overseen by just a single artist in a limited period of time. With the Ha Baroana and Mutoko one senses a whole community of artists shaping and re-shaping, celebrating and embellishing over the longest time.