Hope: Tendani Mulaudzi’s journey through drug addiction – using ecstasy and cocaine – ended in her recovery and setting out on a new path in her life. Photo: Supplied

Tendani Mulaudzi once envisioned a future in courtrooms and newsrooms.

A sharp student with ambitions of becoming a lawyer and later a hard news journalist, she was poised to follow a conventional path to success.

But before she could cross that threshold, addiction intervened. Her descent started in school, at the age of 14, where harmful substances offered a shortcut to belonging.

But each time the euphoria faded, Mulaudzi was left to deal with her difficulties alone.

She spent three years in a rehabilitation centre — as a patient and a counsellor — fighting through relapses, loneliness and with herself — before she discovered writing as a way to heal. She used it to transform her life and help others.

“Whatever I was using was a way to escape any feelings. It would make me feel numb for a little bit, and then I’d do something stupid, or I would hurt someone, I’d hurt myself, or I’d embarrass myself, and then that shame would come back,” she said.

“It’s like a vicious cycle, because I keep on trying to numb my shame, but I’m constantly putting myself in situations [where] I actually get more shameful as the time goes by.”

Mulaudzi was 14 when she started drinking alcohol — socially at first to feel accepted by her school friends — but moved on to experiment with harder drugs that gradually disrupted every area of her life.

“I remember trying MDMA and I loved it, because it’s like a love drug. You just feel euphoric and you want to hug everyone and love everyone. That’s when I would say things started to get a bit tricky for me, and I would find any excuse I could to use MDMA [ecstasy].”

Her reliance on drugs heightened after her father died when she was 20 and still studying for her undergraduate degree.

Instead of grieving his death, she threw herself into academia, supplemented by harmful substances.

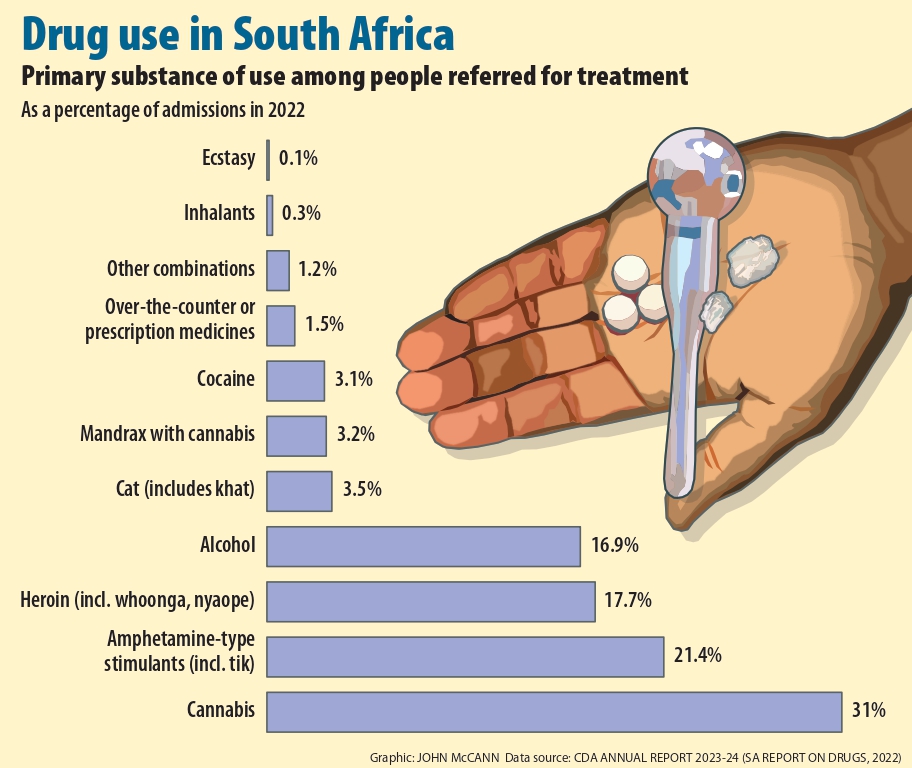

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

She was pursuing a post-graduate degree in law, but cocaine robbed her of that opportunity.

“I went to a club with a friend in January of that year, and that’s when I tried cocaine. That was, I think, when things really, really changed for me, because this was a drug that made me feel so good.

“I was intoxicated, but I could be in control, and I felt really confident and social, and that sort of did for me all the things I couldn’t do for myself. Essentially, it gave me the confidence that I felt I needed.

“That was when things started really unravelling for me, and I had my dad’s life insurance money, so I spent it all on things like partying and drugs and friends.”

Her addiction and social life took precedence while her studies, work and career began to suffer. It became worse when she started using cocaine on her own.

“It was very secretive. It was very isolating, and I could mask it pretty well,” she said.

“I had this double life thing down, where I presented myself as someone who was put together for the most part, but at home, I was just using.”

The following year she landed her dream job as a news reporter for EWN, but her addiction stripped her of the opportunity to “make it big” in South African media.

She said her work ethic, appearance and approach to life deteriorated — she often lost herself in shame, denial, guilt and self-sabotage.

“If my superiors asked me what was happening, even though they were coming from a caring point of view, I took it as an attack. It made me feel very defensive. So I created this narrative that everyone was out to get me, that they all hated me. There was no responsibility or accountability on my part.”

Mulaudzi was encouraged to seek treatment when she was 26 years old. That was the first time she admitted to being an addict.

She started her recovery journey in rehabilitation when she was 27. It was a brave step, but also an intense one.

“At the beginning, I felt very humiliated, hopeless — lots of hopelessness — a lot of feelings of, ‘I can’t come back from this, like I’ve done too much harm, and I don’t see how I can actually regain a life of meaning.’”

She relapsed three years after recovery. That felt like she had lost everything, including the time she took to recover. But she drew strength from the tools she’d learnt in rehab, helping her pick up the pieces and try again.

“It’s not easy at all. I think it’s one of the most difficult things anyone can do in their lives. But I grow. I can see myself growing every day. Sometimes I feel like I’m regressing, but that’s fine. Most of the time, it’s like, two steps forward, one step back, you know, which is fine.”

Mulaudzi took up writing as a coping mechanism when she was in rehabilitation, and when she became a counsellor in the same place, she shared this with others.

She is writing her first book and works as a wellness coach, mental health advocate and freelance journalist. She also hosts the Liberite Writing workshop to help others who are battling with addiction, depression, anxiety and grief.

“One of the things I believe in is to write alongside the people that I facilitate, and then share our experiences. It is really beautiful, because it’s that thing of relatedness or relatability, where like people could relate to one another through sharing.

“There is no help as powerful as one addict helping another.

“I found my purpose through my experience, because I thought that I could never be a journalist again, and maybe that’s because I wasn’t meant to be a hard news journalist. It’s not really my calling, but that’s what I found out, and that’s how

I started to appreciate the person that I am.”