Nokuthula Mabaso, centre, and other mourners from eKhenana attend the funeral of Ayanda Ngila at his family home in Mthalala village in Port St Johns, Eastern Cape. Photograph: Rogan Ward

Last week, South Africa commemorated the 10th anniversary of the Marikana Massacre. But a slow and painstakingly thorough bloodbath of Durban’s shack dwellers has been taking place for the past 15 years.

The target

On 20 August 2022, in the early hours of the morning, under the cover of darkness, two armed men snuck into the eKhenana Commune, a collective led by the shack dwellers’ movement Abahlali baseMjondolo. Everyone was asleep and no one saw them as they moved among the shacks looking for their target.

Footage from CCTV cameras (installed by the community after the assassinations of Ayanda Ngila and Nokuthula Mabaso) shows that the two men first went into the community hall (which doubles as the movement’s Frantz Fanon School). It was empty.

Then they moved on to the communal kitchen where members sometimes sleep. No one was there either. Searching through the rooms of eKhenana’s chicken coop, still they found no one.

Eventually, however, they arrived at the home of Lindokuhle Mnguni, the chairperson of the commune.

The safe house

For the past year, Mnguni has been sleeping in a safe house far away from eKhenana. There were already threats against him and attempts on his life because of his role in founding the settlement and challenging the stranglehold that local mobsters have on housing developments in the Cato Manor/Cato Crest area.

After Ngila and Mabaso were assassinated, the need to use the safe house was underlined. Mnguni would visit eKhenana during the day under the protection of other members of the movement; but once night fell, he would leave his true home for the protection of this clandestine refuge.

It was no way to live and Mnguni hated living in fear. He was committed to the struggle and willing to give his life for his community. But he was also under pressure from his comrades to take these precautions. They told him that they could not lose yet another leader of the movement. So, religiously, he would return to the safe house each night.

On the night of 19 August, however, Mnguni finally let down his guard.

After just finishing a meeting at the community hall that had run overtime, Mnguni insisted to another movement leader that he was too tired to travel. Assuming that no one aside from close comrades knew about his presence at eKhenana, he rationalised that he could safely retire to his humble home that he had not slept in for the better part of the year; he would leave at first light that Saturday morning before others had risen.

Besides, most of the Ngubane family, the people linked to Ngila and Mabaso’s murders, were now behind bars; things were looking up, and the settlement had been quiet for months.

Forgetting vigilance this one time was just too tempting: Mnguni would get to sleep in his own bed, in the warm arms of his partner, among a community he loved and believed in. Though the risk seemed low, this one miscalculation proved fatal.

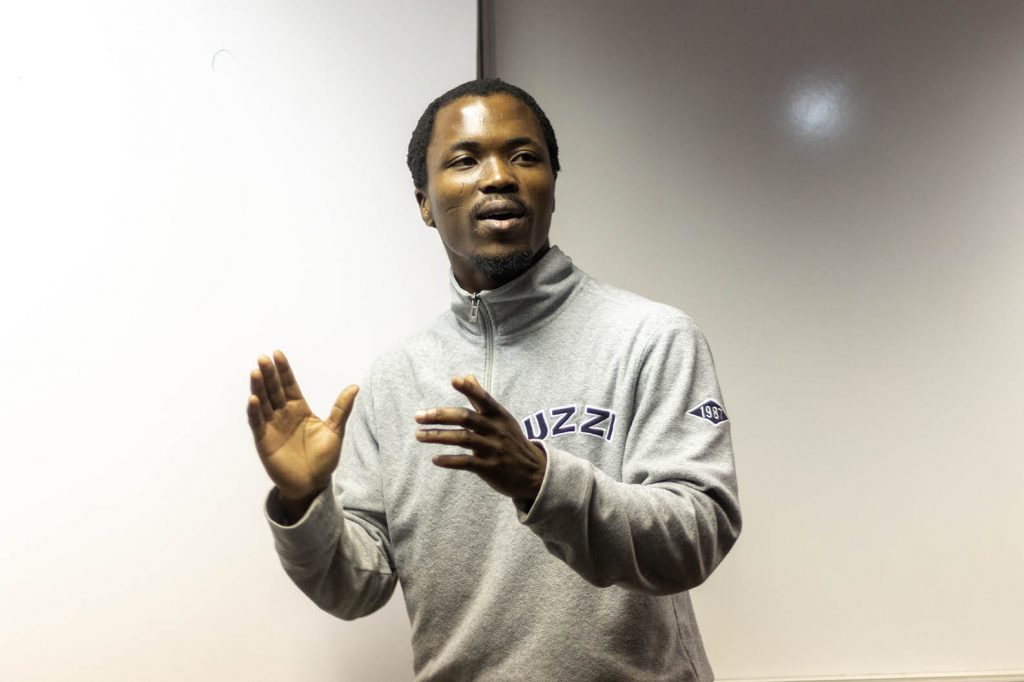

Lindokuhle Mnguni.

Lindokuhle Mnguni.

The assassination

The two men who snuck into eKhenana were professional hitmen. They knew how to get around undetected. They knew all the places their target might be. And they knew how to shoot to kill.

When they reached Mnguni’s small home, they found him and his partner there asleep. The two men grabbed a spade and smashed the window so that they could get a clear shot inside. They fired only a few shots. That is all it took. Mnguni, only 28 years old, was killed almost immediately. His partner was shot too and is in a critical condition.

As the residents of the commune awoke to gunfire, rushing to see what had happened, the hitmen fled the settlement into the dark night. Those who saw the men escape identified them as being responsible for the killing of Ngila.

Residents rushed Mnguni’s partner to the hospital where she was saved from meeting the same fate as he did. But though they tried, saving the community’s chairperson proved impossible.

Mnguni was not just an activist but was also an organic intellectual and avid reader. He hated racism and capitalist greed. He was a selfless young activist and pan-Africanist. He was a committed feminist, not just in word, but more importantly in deed. He believed with all his heart in the struggle for equality for all human beings, no matter where they find themselves. He has left us, gone too early to meet his ancestors.

The unseen Marikana

The Marikana Massacre is known as the largest single massacre in post-apartheid South Africa. But not all massacres occur in the space of a few minutes. There are also seemingly hidden massacres that take place over a long period. As individuals are picked off one by one, we often do not notice that the killings constitute a deliberate and brutal slaughter.

Over the past 15 years, 24 leaders of Abahlali baseMjondolo, the largest independent social movement in South Africa, have been assassinated by hitmen or by police. Many more members of the movement have also been attacked and have landed up in hospital on the cusp of death.

Why does this keep occurring? Each individual case has a different immediate cause. However, the killings are well organised and targeted. There is a wider context. Every one of these killings have occurred because these activists challenge the powerful and corrupt status quo, a state of affairs maintained in KwaZulu-Natal by the ANC.

We may not see it as a massacre because it does not occur all at once. But make no mistake, the brutal slaughter of Abahlali members is systematic.

It will continue until we begin to treat the lives of poor black shack dwellers as morally equal to the lives of wealthy white residents of Umhlanga, Sandton and Camps Bay. It will continue until we begin to value poor people’s lives over rich people’s profit. It will continue until we act. If we proceed and do nothing, we will all be culpable for failing to stop the carnage.

Jared Sacks is a South African PhD candidate at Columbia University. He is the founder of a non-profit children’s organisation and has worked as a freelance journalist and political commentator.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.