Defiance: South Africans attend a rally to protest against troops in the townships. (David Turnley/Corbis/VCG/Getty Images)

What did it mean to be a white person in a struggle that was widely perceived to be for the liberation of black people and almost entirely involving black people as cadres and combatants?

The involvement of white people entailed something more than joining and being “welcomed” in the organisation(s), if that were possible when operating underground.

It necessitated self-awareness on the part of white people as members or leaders in their relationships with black people. Sensitivity was necessary in interactions to recognise — especially in situations of open legal struggles — that most white people entered with advantages in terms of their opportunities to acquire formal education and skills.

These were needed in the struggle but they also opened possibilities for stress, where those with the skills consciously or unconsciously made many of their black comrades feel inadequate through the wielding of this knowledge.

Knowledge is power and one had to be conscious of the need to use that knowledge to empower rather than subdue others without that level of formal training.

It was also necessary to recognise that the liberation struggle was itself a place for all to learn.

Whiteness examined

Whiteness needs to be discussed as part of an awareness of self and others and how we are differently located and what we have been able to take for granted about the unfolding of our lives and opportunities presented to us.

When people speak of race it generally does not refer to white people. White people are the observers of “races” or, in earlier times, missionaries or anthropological researchers or colonisers, regarding the Other. White people in whiteness discourse are never the Other.

Even in a liberation struggle dedicated to non-racialism, race is relevant. It ought not to be erased as a factor even with a fervent embracing of non-racialism. In a struggle where one works with others committed to equality, there are inequalities between comrades. These need to be factored into our understanding of how we relate to one another.

Being a white person in a national liberation struggle, historically and now when liberation struggle activities may be carried out in a range of spaces and ways that are different from before, requires considerable self-awareness of what that whiteness signifies.

One had to show that one was ready to do what was required and not expect praise or rewards.

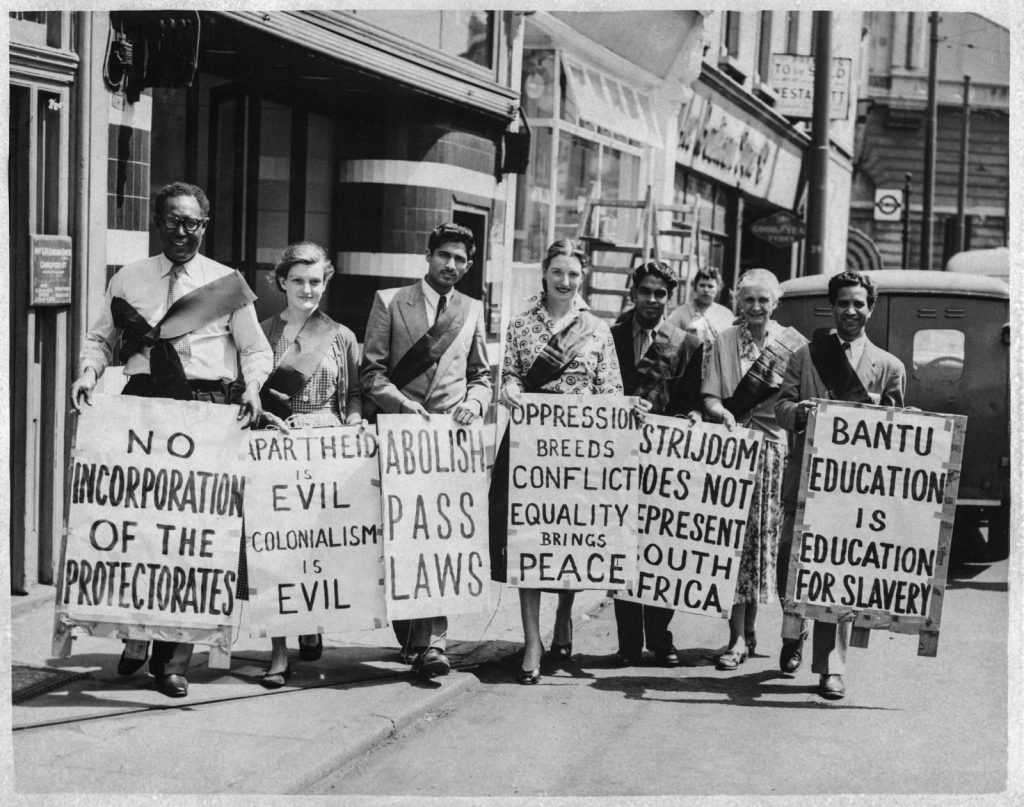

Members of the Movement for Colonial Freedom in the United Kingdom and the Black Sash Movement march to South Africa House in London to deliver a memorandum to South African prime minister JG Strijdom. (Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/Getty Images)

Members of the Movement for Colonial Freedom in the United Kingdom and the Black Sash Movement march to South Africa House in London to deliver a memorandum to South African prime minister JG Strijdom. (Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/Getty Images)

Continual self-reflection

Joining with black brothers and sisters required new learning, beyond “signing up” and reading what appeared in strategy documents. And what one needed to learn had also to be a “part of the everyday life experiences” of the black comrades. It is an issue that can present itself in more than one way and at different periods of one’s involvement.

There are levels of understanding of what it means to relate to a black person that cannot be couched in the language of non-racialism or constitutional rights or opposing national oppression or racism, or clearly articulating the concept of respect for human dignity and similar values. It is not simply wording or articulating sentiments.

Relating to black people in depth also means trying to unpack the broader experiential elements of being black compared with being white, which affects how they relate among themselves and also how relationships with white people are understood conventionally, and in the organisation.

This is not simply reducible to racism and insults, considered at an abstract or conceptual level where one refuses to countenance any form of racism, and takes a stand together with black people or as close together physically as one could be under apartheid.

For many white people, the turn to the struggle may not have been directly related to experience (although what many of us witnessed was an important influence). It may often have been intellectual and moral, albeit without the direct experience that only black people had.

Some may have been influenced by opportunities to witness aspects of what most black people in the struggle experienced in the minutiae of their lives.

Minutiae refer to details that are important to understand if one wants to grasp the texture of the lives of black people, to experience what was happening before, in the sometimes invisible background and after whatever we may have encountered in political meetings.

Joining the struggle needed learning beyond the original step of association, or linking up with an organisation of the oppressed, important as that step was. That entailed “oneness” of a limited kind. An affirmation that one “stood as one” needed to also appreciate the distinct social location and experiences of the different components of that unity.

Protest: In 1961, white students in Johannesburg demonstrate in front of a jail where black people are detained without trial. (AFP)

Protest: In 1961, white students in Johannesburg demonstrate in front of a jail where black people are detained without trial. (AFP)

Location

On the one hand, one needed to understand how one was (and is) located as a white person, what resources one commanded, how one stood in relation to the black people, and what advantages and disadvantages white and black people brought into that relationship. One needed to ask whether any such difference in resources that one had as a white person led to inequality inside the struggle organisations.

In my involvement in the ANC-led liberation movement, I did not have the opportunity to work with others for most of the time from my recruitment in 1970, until I first emerged from prison in 1983.

In prison, I did work with comrades, but we were all whites. It is only in the period of the United Democratic Front (UDF) that I came to work with black people, although I had worked with a small number when I was a liberal student in the National Union of South African Students at the University of Cape Town in the 1960s.

With the formation of the UDF in 1983, I came to be involved with individuals and organisations from all sections and a lot of my work entailed visits to townships, as part of the provincial leadership and later as one of those relating to the rise of popular power, advocating its potential practices in speeches and writings. In these township visits as well as interviews I learnt about local experiences.

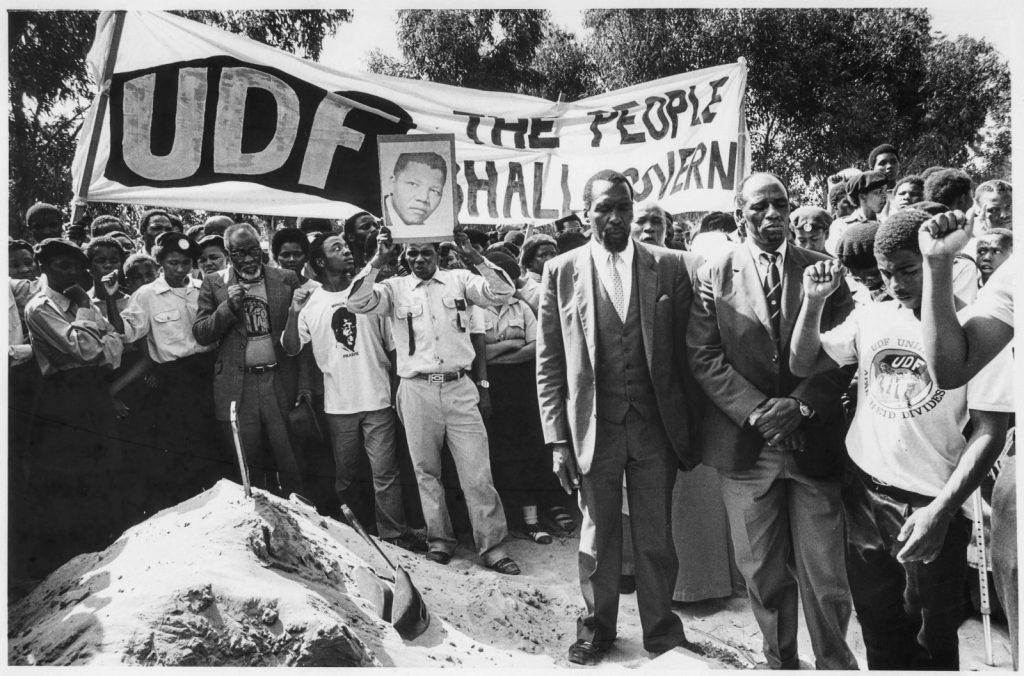

Members of the United Democratic Movement attend the funeral of a UDM activist. (Eli Weinberg/Robben Island Mayibuye Archive)

Members of the United Democratic Movement attend the funeral of a UDM activist. (Eli Weinberg/Robben Island Mayibuye Archive)

Release from prison

I was initially cautious about being involved in public activities when due to be released after serving my first period of imprisonment — as a sentenced prisoner — in May 1983. I had planned, as others had done before, to leave the country on an exit permit that would not have allowed me to return. This was because people were placed under close police surveillance and heavy restrictions, and had great difficulty finding work or playing any political role.

But there had been a shift in the political climate. This meant it was no longer inevitable that I would be banned on release. And it seemed possible, if I proceeded cautiously, that I could play a constructive role in undermining the apartheid regime while in the country.

This was a position that we, after discussing the matter as a collective in prison, had reached at a very late stage. We changed our position at the end of 1982, a few months before my release, and decided that I should remain in the country. It forced me to confront my fears and also the privileges of my whiteness.

This was a political choice. But it was also a difficult personal one. I did not want to go back to jail. I longed for peace, quiet and a contented family life. I dreamed of a tranquil home life, uninterrupted by police attention or the threat of it.

But I asked myself this: “If I were a black South African, without any opportunities to take up a professional career or emigrate, would I then consider withdrawing from politics?”

I had made my choice in the late 1960s to throw my lot in with those wanting to change South Africa. I considered it important that I, as a white person, should not demand less of myself than I did of my black comrades.

The UDF experience

When I worked in the UDF I had a range of experiences in the three years between my release and re-detention in 1986, doing things I had never done before, hearing voices I had never heard, seeing things I had never seen.

This was exciting but also a learning curve. I had read about the “masses in action” and “mass creativity”. In the 1980s I saw “the masses” I had read about in revolutionary texts.

I was elected to the then-Transvaal executive of the UDF, charged with conducting political education. We had periodic meetings of the executive in Khotso House in Johannesburg, where our offices and many other progressive organisations were located. (Because of these activities I was forced underground in the first State of Emergency from July 1985 to February 1986).

I had a car and was able to drive to and from UDF meetings. Some of the leading officials of the UDF in the Transvaal, such as Paul Mashatile, then one of its general secretaries, did not have transport and I used to return him to Alexandra township after meetings.

When I was in this position, I was working and paid a salary as a law lecturer at Wits University. Many of the people who worked for the UDF had no remuneration. They would go to the office and were given money for transport.

I was not aware of all this immediately. I did not fully understand then that part of being a white person in the struggle is that one ought to be inquiring and finding out about the conditions of others in the struggle.

I’m not sure that I was sufficiently careful to find out about the conditions under which black comrades lived and took part in UDF activities. In truth, a lot of the comrades who worked for the UDF in various capacities were not paid and had few changes of clothing. One practical result was that if the police were hunting for them, their clothes made it easier to track them down.

When we held a regional or provincial meeting, how did I get there and how did comrades from the townships travel? How did they raise the money and were they compensated at all for whatever they paid in transport? What were the hazards involved in their reaching these meetings and returning home, compared with my relative safety, when not on the run myself?

I must admit I did not inquire about these things. Having some idea now of the dangers of transport, by train then or by taxis, one needs to ask whether we took sufficient steps to ensure that meetings and the hours of meetings did not put people, especially women, in danger.

But also given that many of the people who participated were only partially employed or unemployed and often living in insecure conditions or homeless, what did we do to accommodate that, not only in the UDF offices but more generally?

Learn and teach

How does one use one’s higher formal educational qualifications? This is important to interrogate because knowledge is not only power, but a potential weapon deployed not only against the enemy but against comrades. It can be intimidatory, used to ram through one’s position, or make others fear to raise objections.

The question that white people who have these skills need to ask is how to make knowledge and expertise an inclusive quality, by transmitting them in a way that they are owned by all participants to become similarly empowered.

Formal learning is only one knowledge base and those who have

university degrees can learn different and profound lessons from people with little formal education. And it is exemplified by Moses Kotane, who had no formal schooling, and Walter Sisulu, who had standard two before being imprisoned on Robben Island.

I am not sure whether I initially believed I would learn from encounters with people who had little formal education. But I came to study and experience the quality of intellectualism that does not derive from professional training and to benefit from it.

Prison: Raymond Suttner leaves the Durban supreme court in 1975 after being sentenced to seven and a half years in jail. He was charged on two counts under the Suppression of Communism Act. At the time he lectured law at Natal University.

Prison: Raymond Suttner leaves the Durban supreme court in 1975 after being sentenced to seven and a half years in jail. He was charged on two counts under the Suppression of Communism Act. At the time he lectured law at Natal University.

I gained more than I lost

I never viewed my participation in the struggle as altruism. Altruism refers to doing something to benefit others without any sense of gain. I am not saying that my activities were selfish, but they were not selfless either.

I did not set out to gain, but I gained more than I lost. As I do a reckoning now I believe that I had the opportunity to lead a life that has had meaning. The liberation struggle entailed sacrifice, but it was simultaneously an opportunity to transform my relationship with being a privileged white person. Being part of this common effort would help “normalise” my life.

As I think about my life experiences — in retrospect, for this was not in my mind at the time — I see a lot of my experiences as trying to remedy my relationship with black South Africans, to “fit” into the society where I lived, but in an emancipatory way.

As I think about it, my political involvement was at one level an existential process, whereby I “normalised” my life in what was then a rigidly segregated South Africa.

This set me on a course that would for some time render me both an insider and an outsider, physically present in apartheid South Africa, but taking a course different from that of most white South Africans.

Professor Raymond Suttner served lengthy periods in prison and house arrest for underground and public anti-apartheid activities. His writings cover politics, history, and social questions. In Inside Apartheid’s Prison, he records his prison experiences and subsequent break with the ANC/South African Communist Party.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.