Interim Director of the Centre for Women and Gender Studies (CWGS) Dr Babalwa Magoqwana (centre) with transdisciplinary and gender scholars from Mandela University and partner institutions at the Dr Joyce Banda public lecture in February.

All the Women’s Voices

The Centre for Women and Gender Studies (CWGS) was launched at Nelson Mandela University in October 2019. One of the CWGS’s key academic projects is to research and foreground African women’s biographies, intellectual production and political histories. These speak of women’s power and leadership in society. The absence and erasure of these voices is part of the sociology that contributes to gender-based violence (GBV).

“We see it as our mandate to resuscitate these voices and histories: not only the voices of intellectuals, we want all African women’s voices — workers, rural women, women in business, politics, the arts…” says the Interim Director of the CWGS and senior lecturer in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Dr Babalwa Magoqwana. It is the intellectual cleansing/ukuhlambulula of her story, aimed at healing the systematic and intellectual trauma that defines our society today.

The CWGS is mainstreaming these histories in its teaching and research:

• To develop a gender corridor in the Eastern Cape; and

• To link universities and scholars dealing with gender questions and profiling African women’s biographical intellectual histories.

“We are partnering with other universities in the Eastern Cape, such as Rhodes University, in talking about women’s liberation histories and popularism; how women in the liberation struggle were more than mothers and wives, they were essential to the revolution,” Magoqwana explains.

“We shouldn’t be reading about Sol Plaatje and the history of the ANC without reading about Charlotte Maxeke. In the same vein, we have commissioned a thesis on Adelaide Tambo who is often referred to as the wife of Oliver Tambo, although she was a political force in her own right. This is the kind of erasure of African women’s intellectual history we are combatting. Even in the rewriting of our country’s history, our African brothers have generally neglected the enormous role of women; or referred to them as ‘the wife’ or ‘first lady’.”

The CWGS is currently working on a book on African women’s intellectual histories co-edited with Rhodes University’s Siphokazi Magadla and Athambile Masola from the University of Pretoria. Due for publication in 2021, the book explores the voices of women in all spheres — from pop icon and activist Brenda Fassie in the eighties and nineties to intellectual activist Charlotte Maxeke, going back 150 years.

The CWGS is also exploring what it means to be “Queer in Africa”, based on the work of Professor Zethu Matebeni, the Centre’s first visiting professor, appointed in 2019, who is based in the Department of Anthropology and Sociology at the University of the Western Cape. Her research focuses on gender and sexuality, with specific attention on black lesbian lives, LGBTQ rights and queer issues.

“To show that LGBTQ life is not foreign or Western, it is part and parcel of our own cultures, Prof Matebeni explores the local languages in the Eastern Cape and how they represent sexuality. Her research speaks directly to what is happening in our communities and to the growing conservatism about sexuality in Africa that is often based on religiosity. It challenges dogmatic and traditionalistic approaches that dismiss sexuality as something that should not be engaged with in an African context.”

Prof Matebeni’s films, poetry and essays have been published in numerous journals and she is the co-editor of Beyond the Mountain: Queer Life in Africa’s Gay Capital (UNISA Press, 2019), and Queer in Africa: LGBTQI identities, citizenship and activism (Routledge 2018).

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic and rise in GBV during lockdown, the CWGS launched a digital platform in early April 2020 to build a local and global online community. “We invite people to speak on the work they have published and we encourage students from different disciplines and faculties to participate,” says Magoqwana.

As part of their aim to develop perspectives on the effects of the COVID-19 crisis, the CWGS’s weekly online series Reading with the author began with a focus on health and gender, in a conversation titled “COVID-19: Movement and class in post-apartheid South Africa” by gender activist and prominent feminist author, Professor Pumla Gqola.

“The CWGS is committed to addressing issues to which everyone can relate,” says Magoqwana. “In the Department of Sociology we will be investing in a new curriculum that foregrounds African sociology, to nurture African-centred gender scholars from first year who can see themselves in the curriculum and who go on to pursue Master’s and PhD degrees.”

GBV during lockdown

Gender-Based Violence (GBV) has escalated during the COVID-19 lockdown. While our country is working hard on controlling the virus, very little has happened to control GBV. Mandela University has responded by establishing the GBV Command Centre for anyone in need of help in the Nelson Mandela Bay Metro. The call centre numbers are 0800 428 428 and 0800 120 7867. The university also launched the MEMEZA anti-GBV campaign, which raises awareness about GBV and seeks to improve community safety through a range of measures, including the distribution of yellow whistles, to be blown in an emergency.

Documenting women’s contribution to history is key to academic project

Nelson Mandela University Vice-Chancellor, Professor Sibongile Muthwa

Nelson Mandela University Vice-Chancellor, Professor Sibongile Muthwa

Inyathi ibuzwa kwabaphambili – a Xhosa proverb that means wisdom is learnt or sought from the elders.

This powerful proverb was the overarching theme of the two-day virtual colloquium hosted by the Centre for Women and Gender Studies at Nelson Mandela University, in collaboration with Rhodes University and the University of Pretoria.

The colloquium, held on 28-29 August 2020, served not only as a significant Women’s Month commemoration, but was also the culmination of the first year of the Centre’s flagship intellectual project to recover memory and “re-member” women’s intellectual histories in Southern Africa.

Opening the colloquium, Mandela University Vice-Chancellor, Professor Sibongile Muthwa, said it was aptly themed, and deliberately sought to recognise the generational continuities and discontinuities of the struggle and achievements by women today.

“The discussions contribute to righting the wrongs of excluding women’s historiographies that have fundamentally shaped ideas of personhood, liberation and leadership, yet are largely left out of history and how our common journey as human beings is told,” Prof Muthwa said.

“Inyathi ibuzwa kwabaphambili is a call to action for us to look back while we are building and moving forward, learning from our elders … those who have built the institutions before us; those who have sacrificed so much for so many of us, and for those who are yet to be born. This connection and recognition of the linkages of the history and future of women enables us to recognise the continuities within the challenges faced by women today.”

Two years ago, Prof Muthwa, during her historic inauguration as the institution’s first black African female Vice-Chancellor, foregrounded the revitalisation of the humanities as one of the University’s key focus areas in the renewal of the academic project.

At the time, Prof Muthwa said: “The humanities, with open and malleable borders, are called upon to use their innate potential to awaken African scholarship, epistemologies and systems of thought so as to excavate the African praxes of our regions to write an inclusive narrative of progress. There is a constitutive link between knowledge, teaching and learning and institutional culture. Much of our non-transformative, exclusionary academic and non-academic practices and behaviours are closely knitted into our views of pedagogy, knowledge and institutional ethos.”

The Centre, which was launched in October 2019 under the interim directorship of sociologist Dr Babalwa Magoqwana, is aimed at providing an inclusive “gender agenda” that is informed by the broader transformation project of Mandela University in creating a more humane and equal society.

Through the colloquium, the Centre wrapped up its yearlong academic project of archiving and showcasing the biographical histories of the African women thinkers, infusing history and the creative genres of arts and language to centre the works that have been neglected from the maternal intellectual ancestors.

Opening the colloquium, Prof Muthwa called for the deliberate positioning of the daily struggles of ordinary women at the centre of the conversation, allowing recognition as intellectuals in their own right.

“[This] will add to a broader feminist archival project which seeks to re-member women and fight the continued colonial and post-colonial erasure of women’s intellectual contributions in the political and cultural imaginations in Southern Africa,” said Prof Muthwa.

Supporting the work of the Centre is the Charlotte Mannya-Maxeke Institute (CMMI), which was established to preserve this formidable leader and activist’s legacy by producing the same calibre of African women.

Maxeke, who was a key yet often underrated figure in South African history, is now recognised for the pioneering role she played in the emancipation of women and their overall contribution to society.

Representing CMMI at the colloquium, Dr Musawenkosi Saurombe said: “It is therefore important for us to take note of these contributions that have been made and how this has been a foundation laid for those of us currently continuing with the mandate previously established, and how important it is to continue the work that has been long started.”

The CMMI is working on a programme to commemorate the 150th birthday celebrations of Mama uMaxeke.

ooMakhulu as an Institution of Leadership and Knowledge

Interim Director of the CWGS and senior lecturer in Nelson Mandela University’s Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Dr Babalwa Magoqwana

Interim Director of the CWGS and senior lecturer in Nelson Mandela University’s Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Dr Babalwa Magoqwana

The Inyathi Ibuzwa Kwabaphambili (wisdom is learnt/sought from the elders) of our African Women’s Intellectual Histories conference seeks to centre the intergenerational conversations and recognitions of interdependence of one generation to the other. When we themed the conference, we were deliberate about drawing on our elders in the critical conception of “What is considered knowledge?”, “How do we know what we know?” and “Who is the producer of knowledge?”

It is through our grandmothers (ooMakhulu), our aunts (oo ragadi, Oo Makhadzi), and our mothers that we have shaped our intellectual foundations of knowledge.

It is fitting to acknowledge these maternal contributions from our elders, the status that all of us cannot escape (sonke sizakubadala).

The Centre for Women and Gender Studies at Nelson Mandela University has prioritised the archival project of women’s histories to conscientise our society and reveal the maternal legacies that brought us here today. As the younger women, we carry our mothers’ histories, victories and traumas.

In my own life, it is my late maternal grandmother uMakhulu Magoqwana who inspired me. When I was a child growing up in the rural Eastern Cape she taught me all the vowels, she taught me about my clan names and about the local history and geography of the land.

She told me our stories and folk tales, none of which I received in the education system — such was the gap between what I learnt at home and in the formal education system, where, if you are not certified, you are not recognised for your knowledge and you don’t become a knowledge producer.

Yet we survived and coped with life because of the knowledge we received from people who are not recognised in the system, in our schools and our universities. It propelled me to pursue a scholarship that is healing for all of us, a scholarship that restores the recognition of ooMakhulu, given that recognition is part of dignity and healing.

The Eastern Cape is fortunate to have a rich matriarchal history, yet this is not reflected in the masculinised political culture of contemporary South Africa — where women continue to be marginalised. Structurally, power is constituted as a very masculine affair with women positioned as “the weaker sex”, as perpetual kids whose vulnerability is constantly emphasised, hence we have a Ministry of Women and Children.

Nelson Mandela University’s march against GBV in 2019. On the far right is the university’s Vice-Chancellor Professor Sibongile Muthwa.

Nelson Mandela University’s march against GBV in 2019. On the far right is the university’s Vice-Chancellor Professor Sibongile Muthwa.

This is not how it always was. My grandmother was far more in control than many women in our society today. The leadership of ooMakhulu in the economy and the household was central to the sociology of pre-colonial African society. Women kept their clan names, they did not take the man’s surname — this is a colonial inheritance.

Colonial patriarchal structures, religion and neo-traditionalism concealed as “African culture” systematically erased African women’s role and contribution in African societies. In pre-colonial African societies throughout Africa women shared the work, roles and duties at all levels and they owned land. Colonialism dispossessed women of their land and introduced a genderisation of labour.

We have to challenge how these histories have been written and re-establish women as co-partners and co-producers in society and the economy. Until this happens, until we educate our children differently and restore the dignity of women in our public cultures, and restore the reverence for ooMakhulu, the violence that we see today will continue.

Do not live above your people, live with them

Gender activist Dr Brigalia Bam

Gender activist Dr Brigalia Bam

Dr Brigalia Bam was born in the Eastern Cape and is a prominent gender activist and passionate developer of young women.

She is currently a member of the International Elections Advisory Council, and a former Chairperson of the Independent Electoral Commission and former General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches. She has been awarded numerous international awards, including the Mahatma Gandhi International Award for Peace and Reconciliation; OR Tambo Lifetime Achiever; Ubuntu Award, the Order of the Baobab (Silver) for uplifting women and promoting democracy, and many other recognitions.

She has received numerous honorary doctorates and served as the Chancellor of the University of Port Elizabeth (now Nelson Mandela University) and Walter Sisulu University. She is the author of Democracy: More Than Just Elections (2015).

Dr Bam delivered the following keynote address for the African Women’s Intellectual Histories webinar hosted by Nelson Mandela University on 9 August 2020:

It is 65 years since the Women’s March on the Union Building, and I have lived in this world for more than eight decades, with more than six of those being involved in women’s emancipation struggles.

I have been both a participant and a witness in this history, and I have seen failures and successes in equal measure. It is with this cumulative experience that I would like to share some thoughts, based on the proverb selected as the motto for this seminar, Inyathi Ibuzwa Kwabaphambili (Wisdom is learnt from the elders).

I would like to emphasise that inter-university collaboration ought to be a model for intergenerational collaboration and increased trans-disciplinary efforts across institutional boundaries, with the collective mission to emancipate women. We cannot afford to individualistically compete with each other when we have greater impact complementing each other in collaboration. When we compete we are often unable to complete our mission of emancipating all women; I have lived long enough to know this as a fact.

In South Africa we have no time to waste as the scale, gruesomeness and impact of gender-based violence (GBV) is unprecedented, even though on paper we are supposed to have some of the most progressive laws and constitution. Rampant corruption, a rapidly declining economy, growing inequalities, intergenerational poverty, unemployment, human trafficking and many other social ills are afflicting women with devastating intensity. It places the responsibility on us as agents of change for social justice.

In this respect a great African scholar and activist, Frantz Fanon, said something so profound and yet simple in his book, The Wretched of the Earth, when he proclaimed that “each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfil it, or betray it”. We have an extraordinary legacy of women in this country who have fulfilled their mission. If we head back to the close of the 19th century and the early decades of the 20th century we meet Charlotte Mannya Maxeke, who took a stand to fulfil her mission and become a pioneer and pathfinder for women’s emancipation when it was almost unthinkable, and when the odds were massively against the very concept of social justice for women.

The context may have been vastly different then, but the underlying issues still permeate our society today, despite enlightened policies and programmes. The journey of this great doyen of the women’s liberation struggle still continues today, hence the need for deep reflection, action research and action to address the issues of our time.

As women and scholars of this generation seek answers, it is essential that the research agenda and programmes for interventions have the brutally honest and difficult conversation informed by the following questions: Why have some of our interventions to emancipate women failed? What questions have we failed to ask? What have been our blind spots in the embrace of mainstream literature on women’s issues? With a fast changing societal and global context, what should be our new responsive research agenda?

The role played by our many pioneering women leaders and legends is profound and ought to be our reference point, as should the pre-colonial and colonial epoch of our history, where women played a decisive role that is often not documented in our mainstream literature. In examining women’s intellectual histories we need to make sure that while exploring the celebrated figures in history we don’t forget the vast wealth of intellectual histories of ordinary women in our families and communities who play a profound role in our formative years.

Our examination of women’s intellectual histories should be revisited to give voice to grandmothers, mothers, aunts, sisters and women community leaders who shaped us in our formative years, and whose average real life experiences give us the most realistic picture of what most women go through. It is in mining this intellectual history that we will come closer to comprehending and apprehending the organic experiences of women, thus being able to come up with future research agenda and focal points for our intellectual endeavours on the subject of women and gender studies.

In the current era, we need to closely examine the mega trends shaping the world and how this affects ordinary women in our communities. Globalisation, the rapid advancement of computing technologies and the fourth industrial revolution have fundamentally changed the way we live and do things, and it has had an impact on the condition of women and gender relations. But have we fully grasped what these are and what their implications are in a world of inequalities and digital divides? How do these impact on a young girl and an old woman, for a village woman and an urban woman?

It is my submission that if we put together our efforts to achieve the economic emancipation of women through contextually relevant education, technology, agriculture and rural development and the rebuilding of communities with women playing a central role, we will go a long way in ensuring sustained social justice for women. It is the how, and with what resources and social interventions that our research agenda should resolve.

And so, while we confront the urgent crisis of Gender Based Violence we must at the same time focus on sustainable strategies and solutions for the economic and social emancipation of women in order to break the backbone of patriarchy. The life of Charlotte Maxeke is testimony of a leader who was organically embedded in the communities she represented and for whom she worked. And there are many other women leaders who do the same. It is the alienation of our leaders and public intellectuals today that has created a social distance between them and ordinary women. There must be an articulation between the two if we are to have a catalytic impact.

As we ponder how to ground our research agenda in the real challenges of today, I invoke Charlotte Maxeke’s famous and yet pointed quote: “This work is not for yourselves — kill that spirit of self — and do not live above your people, live with them. If you can rise, bring someone with you.”

This is my appeal to all women academics: to rise above narrow academic career aspirations into activist scholars embedded within the communities on which you reflect. People and activist women of my generation have traversed this road and played our part within the confines of our historical moments. We now hand over the baton to current and future generations to continue with the struggle, knowing that for as long as women are denied social justice, humanity cannot fully realise its potential. You are the leaders you have been looking for: if not you, who will do it? If not now, when will it be done? If not here, where will it be done? Zemk’iinkomo magwala ndini!!

Centering Women’s Studies in Femicide Country

From left: Rhodes University’s Dr Siphokazi Magadla, Nelson Mandela University’s Vice-Chancellor Professor Sibongile Muthwa; former Malawian president Dr Joyce Banda; VOKAL (Valuing Our Knowledge At Last) founder and director Advocate Eve Thompson. The occasion was the public lecture delivered by Dr Banda at Nelson Mandela University in February 2020.

From left: Rhodes University’s Dr Siphokazi Magadla, Nelson Mandela University’s Vice-Chancellor Professor Sibongile Muthwa; former Malawian president Dr Joyce Banda; VOKAL (Valuing Our Knowledge At Last) founder and director Advocate Eve Thompson. The occasion was the public lecture delivered by Dr Banda at Nelson Mandela University in February 2020.

The collaboration between my department at Rhodes University’s Political and International Studies, and the Centre for Women and Gender Studies (CWGS) at Nelson Mandela University, has brought students and academics across generations, disciplines, institutions and continents together.

It has reminded us of the strength and beauty of these community-building partnerships in the midst of a global pandemic. Together we created an online space that gave us an illusion of something “normal”, including a routine seminar space, where we have drawn on our various disciplinary knowledges to contribute to the multiple and urgent questions of women and gender, health, youth, liberation and heritage.

The founding of the CWGS in October 2019 was a result of the activism and vision of women, queer and non-binary academics and students fighting against a patriarchal institutional culture that erases these knowledge makers and an everyday reality of sexist humiliation, rape culture and violence.

In her review of Women’s Studies and Studies of Women in Africa During the 1990s, Professor of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Amina Mama reminds us that, “the almost worldwide emergence of women’s studies as a field of research, teaching and study is generally viewed as resulting from the impact of the international women’s movement on the academic establishment”. The existence and the call for women and gender studies is a reminder that this kind of work is full-time work. At my university, we had the Women’s Academic Solidarity Association (WASA), which was founded in 2004 when Rhodes University was turning a hundred years old.

The women who gathered at the home of Dr Darlene Miller at the time recognised that they could not challenge the white and masculine culture at Rhodes in their individual disciplines. They needed a different kind of leadership, a rotational leadership style, including sociologist Miller and mathematician Dr Phethiwe Matutu as the respective chairpersons of WASA — an organisation built on an interdisciplinary future for women’s liberation.

We hoped for a future where conversations on women and gender would not happen just in WASA-like spaces, but would form part of our core curriculum. We hoped for a future where a centre for women and gender studies and departments from different disciplines would focus on the issues that shape women’s lives, and reflect them in their everyday cultures, teaching and research. It is no coincidence that Miller was the Master’s thesis supervisor to Dr Babalwa Magoqwana, the founding director of the CWGS.

I consider it a WASA victory that the politics department at Rhodes University and the English department at the University of Pretoria are collaborating in seminars, colloquiums and book projects with the CWGS.

Mama asks: “What are the conditions that bestow distinctive characteristics on African women’s studies?” The answer, according to Professor of Leadership, Peace and conflict at King’s College London, and Extraordinary Professor at the University of Pretoria, Funmi Olonisakin, is that we must begin our activism and theorisation “from the spaces from which we are dying”.

It is this urgent reality that should fuel African women’s studies that emerge from the “collective concerns and interests of African women”, says Mama. Therefore, as much as it’s important for political science in South Africa to be grappling with the politics of capture, our energies ought to be focused on making sense and ending femicide in South Africa.

Girl learners from Nelson Mandela Bay at the Dr Banda public lecture.

Girl learners from Nelson Mandela Bay at the Dr Banda public lecture.

What do liberal claims to citizenship mean to women, queers and non-binary people who face an everyday reality of death? Political science, whose history is to privilege male elites, does not offer us the tools to answer those questions.

Our inheritance is an African women’s movement that brought together activists, creatives and thinkers to fight against what our elders called the “triple oppressions of race, class and gender”. This spirit of intersectional collaboration underlies our intellectualism that is at the service of liberation.

The Desire For Black People Is To Be Fully Human

Prof Zethu Matebeni. In December 2019, the Centre officially appointed Professor Zethu Matebeni as its first Visiting Professor. Prof Matebeni is a sociologist, activist, writer, documentary filmmaker, and one of the leading African queer theorists on the continent. She is currently based at the University of the Western Cape (UWC). Her CWGS role at Nelson Mandela University includes teaching, developing short learning courses and supervising postgraduate students.

Prof Zethu Matebeni. In December 2019, the Centre officially appointed Professor Zethu Matebeni as its first Visiting Professor. Prof Matebeni is a sociologist, activist, writer, documentary filmmaker, and one of the leading African queer theorists on the continent. She is currently based at the University of the Western Cape (UWC). Her CWGS role at Nelson Mandela University includes teaching, developing short learning courses and supervising postgraduate students.

It’s odd that in a country like South Africa, higher education hasn’t prioritised centres focused on women and gender studies,” says Professor Zethu Matebeni. “Yes, there are a range of gender studies programmes as well as the African Gender Institute at the University of Cape Town, but it’s exciting that Nelson Mandela University is investing in the first Centre of this kind. This is an important initiative, particularly in the Eastern Cape, as it opens a lot of opportunities for developing scholarship and creating new knowledge. It is a political project that comes at a very crucial time in our democracy when gender-based violence is increasingly spoken about, yet continues to rise.”

LGBTQ+ includes all of these communities:

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Transsexual, 2/Two-Spirit, Queer, Questioning, Intersex, Asexual, Ally, Pansexual, Agender, Gender Queer, Bigender, Gender Variant, Pangender.

Matebeni explains that the CWGS unpacks the notion of “gender” and “sexuality”, “which many people tend to think about in terms of the relationship between men and women — a relationship embedded in issues of violence, because the foundation of the heteronormative idea assumes an automatic gender imbalance where men are superior and therefore women are violated in a range of different ways”.

The CWGS is broadening the gender conversation and unpacking it in ways that seek not to be comfortable. “My framework is through an African queer and gender lens that seeks to understand the intersections of race, class, sexuality, ethnicity and the nation in terms of understanding violence,” says Matebeni.

Students attend a lecture conducted by Professor Zethu Matebeni

Students attend a lecture conducted by Professor Zethu Matebeni

Her interest as someone trained in sociology is to look at concepts of sexuality and the construction of gender in the African context, because it was as a result of the colonial legacy and Western gaze that indigenous forms of sexuality in African culture became taboo. “The effect of this is that sexuality — which is something that African people have always prided ourselves about — was turned into something that made African people feel ‘othered’ and objectified,” she explains. “It was a case of ‘your body looks like this’ and so through the colonial and Western gaze it came to be seen in a particular way — including through the imaginations of white women and men with their ‘taboo’ desire for black women and men. Or the much cited example of how in colonial times Sarah Baartman became an object and ‘not a person’.”

South Africa has always been obsessed with sexuality — we had legislation about who you could have sexual or intimate relations with; and control and censorship of what we could see and could not see, to the point that people were excited to see breasts. The same legislation also banned political material — anything that would excite political thought. How sexuality and political imagination are connected is very interesting.

“I locate black women in the conversation on sexuality and gender because of the legacies that black women have lived through, and the dire consequence of the colonial encounter on black women and black women’s sexualities. I look at what the world would look like if our gaze started with black women’s perspectives instead of men’s perspectives.

“Through my research and teaching I address the desire of black lesbians and all LBGTQ+ people to be fully human. I have therefore put the black lesbian and black queer women at the centre of my CWGS research. I deliberately take this group as a place from where we can view the world, to reveal a completely different worldview. There have been dozens of brutal murders of mostly black lesbians in South Africa. These brutal murders added to the excessive violations and rapes towards black lesbians — to make them feel less than human.”

Prof Matebeni studied Sociology at the Nelson Mandela University, completed her Master’s in Sociology at the University of Pretoria, and an interdisciplinary PhD at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research (WISER).

Previous appointments include senior researcher at the Institute for Humanities in Africa at the University of Cape Town (UCT). She has been a visiting Professor at Yale University and has received a number of research fellowships, including those from the African Humanities Program, Ford Foundation, the Fogarty International Centre and the National Research Foundation.

Matebeni says all women in South African society are vulnerable to sexual violence. Black lesbians, at the same time, occupy a different space in society — challenging and often openly rejecting sexual, gender, and other cultural norms. While sexual violence towards women is generally aimed at abusing power over female bodies, we also understand that the added vulnerability of rejecting black heteronormativity carried a heavy, and often deadly, penalty on black female bodies.

“The desire for black people is to be fully human, and in this reclaiming of humanness the Centre for Women and Gender Studies needs to place women and women’s sexuality at the core, for it is through the unpacking of sexuality and diverse sexualities that we start to see the origins and history of violence against the ‘other’.“There is a wonderful body of work that looks at diverse African sexualities,” says Matebeni. “Diverse sexualities are not a colonial import or un-African. A number of scholars have offered examples from Africa through the centuries, including intimate male embraces in ancient rock paintings and all kinds of same-sex relations between women, including same-sex marriages.

“We challenge people to look at the most powerful women in their lives and to see how they compare to the lesser role that has been imposed on most women in our society. Therefore in our lives and in our research and in our reading of existing texts we need to start thinking about gender in radically different ways. To start actually addressing gender-based violence in our society; we need to understand its origins and start reshaping our view of the world. We need a new game entirely. In women and gender studies we need to be uncomfortable with the binary established between masculine and feminine; we need to break down binaries such as male and female; we need new cultural definitions of sexuality in flux. We need to take our cue from activists, cultural producers and many artists who are propelling a different conversation about sexual and gender diversity.

Books

Co-edited with B Camminga, Beyond the Mountain: Queer life in ‘Africa’s gay capital’ (UNISA Press, 2019)

Co-edited with Surya Monro and Vasu Reddy, Queer in Africa: LGBTQI Identities, Citizenship, and Activism (Routledge, 2018)

Curated Reclaiming Afrikan: queer perspectives on sexual and gender identities. (Modjaji books, 2014)

Black lesbian sexualities and identity in South Africa: an ethnography of black lesbian urban life. (LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, 2012)

#Activist Connexions in the CWGS

Students and postgraduates at Nelson Mandela University played a central role in the creation of the CWGS to advocate for the advancement of gender equality and anti-gender-based violence in higher education and society.

The Centre was launched as a result of several years of activism and discussion among Nelson Mandela University staff and students (though the social activist platform #Activist Connexions) who are concerned about the women and gender-related matters not being mainstreamed sufficiently in higher education. One of the early engagements was the Gender Forum 2014, facilitated by the university’s Centre for Non-Racialism and Democracy (CANRAD).

The CWGS works across all faculties, contributing to pro-active advocacy programmes to build a community that values co-existence and Ubuntu. The primary aim for establishing the Centre is to contribute to attitudinal and social transformation through the promotion of women empowerment, gender equality and equity by way of rigorous critical analysis of the role of economic, religious and political institutions in legitimising and institutionalising gender, sex and sexuality disparities.

Three of the student drivers in the CWGS are featured here:

Nangamso Nxumalo, Final year BCom Law, Nelson Mandela University

Nangamso Nxumalo

Nangamso Nxumalo I am interested in the economics of gender, in particular women and class. I draw on economic and legal tools of analysis to research how women in the informal sector organise themselves; and how the developmental objectives of urban and rural women in the Eastern Cape, and across the African continent, differ in terms of the communities in which they live. Ultimately, I want to use my degree(s) to contribute to policy that is appropriate to the informal sector, as this is where the majority of people in our country are situated.

Activism is familiar to me given the history of my family. When I got to university I resonated with the gender movement and then my own activism was activated. My understanding of gender has developed over time and it is still developing.

I came to understand how pervasive sexism and patriarchy is from general observations, ranging from women having to put up with catcalls and comments when walking down the street to not feeling good enough about myself. It was through scholarship — reading, researching and constant conversations — and experience sharing where I got to really understand the debilitating effects of patriarchy.

What also deeply concerns me is how different classes of people get treated differently. For instance, I see how “classed” or “privileged” women get treated differently to other women (because of their “Model C” accent or because they are perceived to be more educated or from a richer middle class background, or because they are conventionally attractive according to the marketing, advertising and Western idea of beauty that we get fed).

Even among black women activists, the effect is that many women in this “class” tend to start consciously or unconsciously exceptionalising themselves and seeing women from other backgrounds — such as poorer or “underprivileged” women and rural women — as “the other”. This sense of exceptionalism usually results in a watered-down execution of our politics, and that’s a problem. Nobody should be pushed to the fore as the voice of “the group” because of a perceived accent or appearance. We need to value women from all walks of life and encourage people to be themselves so we can ultimately work together as equals fighting against common structural issues.

Nomtha Menye, Sociology Master’s student, Nelson Mandela University

Nomtha Menye

Nomtha MenyeMy Master’s thesis is grounded in exploring the spiritual significance of water amongst the amaXhosa.

I was born and bred in the Eastern Cape province, and at least once a year we used seawater and sacred rivers such as the Isinuka springs in Port St Johns as sites of Intlambuluko (spiritually cleansing). South African historian, academic and educator Dr Nomathansanqa Tisani explains in her work how this process is performed with the intention of healing the body and making the inner person whole. Ubuntu is achieved through respecting the body as a spiritual being and not its physical appearance.

I believe the traumatic experiences of women in this country need interventions like this that go beyond theories. We need practical interventions that are grounded in the ethnographic study of the Eastern Cape girl child. Research must start at home with the people at home.

This research is of importance to me personally, as I come from a family of successful independent women. These women are not exempt from patriarchy and misogynistic men. It is the constant navigating around such behaviours that makes gender activism so tiring. I also grew up seeing women who never objected against gender-based violence (GBV). It concerned me, and it was only when I became an activist and faced misogyny head on that I understood we cannot all be activists. It takes a different kind of being Iscaka (servant) to partake in this gender war that seems endless. Studying sociology and being part of organisations such as the CANRAD at Nelson Mandela University — which plays a fundamental role in excavating archives of women who have achieved the unimaginable in their time — gives us strength. We find strength in all the women who have gone before us. The archives provide platforms for academic cleansing and making the inner person whole. These are the kinds of spaces of Intlambuluko I speak about in my research; spaces that critique the erasure of women in history.

These platforms also provide thinking and engagements hubs for students. Many students, past and present — our #Activist Connexions — were part of the formation of CWGS. Therefore, the launch of the CWGS on 3 October 2019 symbolised the cutting of the ribbon of our collective efforts.

My aspirations for the CWGS are centred on challenging the ideas women once took as truths, taking into consideration that the biggest challenge is not the decolonising theory, it is taking the theory into realistic praxis. Re-imagining a space of seeing bodies as spiritual beings and not their physical appearance. A space of Intlambuluko.

Nobubele Phuza, Sociology PhD student, Nelson Mandela University

Nobulele Phuza

Nobulele PhuzaI started my PhD this year after graduating with a Master’s in Sociology on gender in sport. I looked at the meaning of “emphasised femininity” and the expected or conventional attributes for sportswomen. My research focuses on netball, which has reflected and reinforced ideas of culturally valued femininity. Netball is socially accepted as an “appropriate” sport for women, evidenced by its promotion for girls in schools, the number of teams, clubs and leagues in existence and the invisibility of men’s netball in the media and society.

I hope the research will help to (re)centre women in discussion of gender and sport and add to the conversation around gender socialisation by problematising the taken-for-granted cultural practices that we engage in every day.

My doctoral study focuses on the mechanism and architecture of protests related to gender and sexual justice in South African universities. It traces the divergence of #RUReferenceList, #RapeAtAzania and #IAmOneInThree, as the most notable components of the #EndRapeCulture campaign, from the historical Silent Protest, motherist movements and androcentric #FeesMustFall movement. I will be satisfied if the study invites broader understandings of liberatory politics and theories of our time that bring feminised resistance from the periphery to the centre of scholarly and political debate. To be clear, I want women’s resistance to be taken seriously, on the ground and in the academic field.

Like every other woman, I always feel suffocated by the requirements of conformity to socially acceptable femininity. I am glad to have spaces like the sports field which allow me to walk that line of athleticism which is neither masculine nor feminine. It would be great to have that feeling spill over into everyday life.

I suppose I’d be more satisfied if gender functioned like a T-shirt: on one day I might dress in a conventionally more masculine way, on another day I wear my netball outfit with its embedded femininity, voluntarily buying into everything society means when it says “woman”. I’d fluidly move between the two, but at the same time I am keenly aware that making those transgressions can make South Africa a very unsafe place for me as a woman. As women we have to think about our own safety all the time, because the reality is that we are not safe. As women we need to be constantly manoeuvring through and around the complexities of agency and GBV. I’m looking forward to a time when things aren’t like this anymore.

African Feminist Imaginations

Professor Pumla Dineo Gqola

Professor Pumla Dineo Gqola

Professor Pumla Dineo Gqola was appointed to the Centre for Women and Gender Studies (CWGS) in May 2020. She is a Professor of Literature, with specific focus on African feminism, African literature, postcolonial literature, and slave memory.

She has just been announced as the holder of the National Research Foundation (NRF) SARCHI Research Chair on African Feminist Imaginations awarded to Nelson Mandela University in November 2020. The Chair comes at a time when the country is seeking answers and solutions to the gender-based violence (GBV) crisis. The chair serves as direct institutional response and intention to ending gender inequalities and boosting transdisciplinary academic research on gender issues. It will attract top postgraduate students from across the continent and build an African research feminist hub in the Eastern Cape.

Miriam Tlali – Writing Freedom

Gqola’s book on South African novelist, short story writer and essayist, Miriam Tlali (1933 – 2017), Miriam Tlali, Writing freedom is in press with HSRC Press. In 1975, Tlali became the first black woman in South Africa to publish a novel in English, titled Muriel at Metropolitan.

This is an excerpt by Gqola from her presentation on Tlali during the colloquium hosted by the CWGS in August 2020 on African Women’s Intellectual Histories/Inyathi Ibuzwa Kwabaphambili.

In an interview shortly after the publication of Tlali’s fourth book Footprints in the quag (David Philips, 1989), author Cecily Lockett asks Tlali: “Would you call yourself a feminist writer?” This is a question that confronted Tlali many times, one she answers with clarity in the affirmative. She underlines hers as a feminism highly cognisant of how race and other indices of power work and impact it: her feminism is not about the primacy of gender or the attitudinal sexism as per the “narrow Western feminism”, but about patriarchy as structural and perpetually collaborating with other institutional systems of power. Importantly, her feminism is not just a South African feminism, but is part of a body of radical black women’s writing from all over the world, similarly concerned about the interlocking forms of oppression. Here she mentions Flora Nwapa, the first woman novelist in Nigeria.

Whereas other feminists in the Black Consciousness tradition, like Mamphela Ramphele, have argued that men were blind to their misogyny, Tlali sees patriarchal investment as deliberate and conscious. Rather than a romanticisation of mothering or even mother-son relationships, which is everywhere evident in the magazine Staffrider at the expense of the figures of mothering characters, Tlali positions the subordination of women as a wilful act by men.

Tlali is widely known for her novels, but far less attention is paid to her non-fictional work in the form of her substantial body of essays and her column “Soweto Speaking” in Staffrider magazine, particularly in the first five years of Staffrider, from 1979.

In Staffrider, political transgression, coded as heroism, named as “staffriders”, is written as exclusively masculine terrain in Staffrider fiction, while women are habitually and theoretically written out of heroism, through violence — as raped bodies — and through silence — as stoic suffering wives and mothers — thus ensuring that they cannot be staffriders.

Tlali’s position at Staffrider is a complicated one. She is one of the founders of the magazine, yet she “disrupts” the central masculinised tenets of the magazine through her painstaking attention, not to heroic masculinity but to “the ordinary”. This carved for her an intellectual space that enabled her to critique dominant ideologies of Afrikaner nationalism and white supremacy through ordinary people’s stories and life experiences.

Tlali’s columns are far more than a record of black life, as they are often read. She reveals the anxieties produced under apartheid, she reveals the complexity and paradox of relationships in the shadow of apartheid and unmasks the stories of male characters who are both hero and villain.

In 1988, Tlali said in a paper delivered in Amsterdam before the Committee Against Censorship: “To the Philistines, the banners of books, the critics … We black South African writers who are faced with the task of conscientising our people and ourselves, are writing for those whom we know are the relevant audience. We are not going to write in order to qualify into your definition of what you describe as ‘true art’…. Our duty is to write for our people and about them.”

In Staffrider Vol 2, no 3 (July/August 1979), Tlali narrates Mrs Flora Mooketsane’s story about the difficulty of accessing her late husband’s pension. Titled “The Soweto ‘not-so-merry-go-round’: An Interview”, Mooketsane’s tells us that her husband died on 17 November 1976 and how she was pushed from pillar to post — from the Bantu Commissioner’s office in Braamfontein to the West Rand Administration Board (WRAB) offices for her late husband’s cards — to the Labour office and eventually being handed a cheque:

They filled the cards, and at the same time, gave me a cheque for R16.00 which, they said, was my husband’s pay for the week they had not paid him for AND his holiday pay which was due at the time of his death.

‘Is this all I must get?’

‘Yes.’

‘How can it be? My husband has been working all along. His ‘unemployment’ (U.I.F.) has been withdrawn from his pay all these years; he has never drawn it.’

‘It’s your fault. You said your husband was a Botswana person.’

‘I never said that. How can I say that? My husband was born in Zeerust in the Transvaal. He only changed his pass and took a Botswana passport. He has been working here all along and he lived here all along.’

‘There’s nothing we can do for you.’

She keeps fighting and going back. Her anger is palpable. She elicits the help of her brother-in-law to no avail, and eventually decides at the end of the column to approach the Black Sash for assistance.

In Staffrider Vol 2, no 4 (November/December 1979), Tlali speaks to policeman Sergeant Moloi in his “comfortable home” that he shares with his children and grandchildren in Rockville. He is a veteran of the Second World War and describes himself as a “good” soldier; he has travelled across the globe, and was a prisoner of war in Egypt about which he related how he was united with a white former colleague of his whom he had not seen since they were municipality policemen “arresting Africans for passes” in the streets of Johannesburg. Sergeant Moloi was then a Sergeant Major and Van Eck a driver stationed in Marshall Square (now known as John Vorster Square).

He related how later, as war prisoners in the hands of the Germans, they parted because Van Eck would not attempt to escape. Being the daring soldier he was, Sgt. Moloi decided to adhere to the instructions he had received while undergoing training as a spy in his country to ‘always try to escape’. He and a friend named Shawa took the plunge and succeeded. Then began Sgt. Moloi’s long, arduous and heroic journey of twenty days through the desert, in the midst of which Shawa resolved to take a different direction, and he wandered alone. Finally, exhausted, hungry and thirsty, but as determined as ever, Sgt. Moloi stumbled into El Alamein and the safe hands of the Allied Forces. As a trained spy, his expert knowledge and wide experience in the desert led to the successful destruction of enemy camps in the desert and to the sinking of ships.

About Professor Gqola

Professor Gqola holds a DPhil in Post-Colonial Studies from Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München in Germany, and MA degrees from the Universities of Warwick and Cape Town.

Gqola is a product of the deep intellectual histories of the Eastern Cape, growing up in a family of intellectuals from the University of Fort Hare, Alice campus. She became the Dean of Research in the same university in 2018, following a decade in the School of Literature, Language and Media at the University of the Witwatersrand between 2007-2017, where she rose from associate to full professor. She has previously been Chief Research Specialist at the Human Sciences Research Council, and taught at the Department of English and Classical Culture, at the University of the Free State from 1997-2005.

Professor Gqola is the author of five books, including the pioneering study What is slavery to me? Postcolonial/slave memory in post-apartheid South Africa, and Rape: A South African Nightmare, awarded the 2016 Sunday Times Alan Paton Award for Non-Fiction. In 2019, she was appointed to the DHET Ministerial Task Team to advice on matters relating to sexual harassment and gender-based violence (GBV) in public universities in South Africa.

The Unmemory and Memory of Women in Liberation Struggles

Radical ecofeminist Professor Patricia McFadden.

Radical ecofeminist Professor Patricia McFadden.

A webinar in October 2020, hosted by the CWGS in collaboration with the Trade Collective think tank led by the activist scholar and researcher Lebohang Pheko, explored ‘The Memory and Unmemory of Women in Liberation Struggles’ and the tensions and hostilities that many women still experience from the states for whom they fought. Pheko initiated the partnership with the CWGS which set out to determine historical truths through the excavated memory of black women. This memory is very different to the male version of the role of black women in the liberation struggle; one in which women are reduced to “motherism” and referred to as ‘‘the mothers of the nation”, which effectively and conveniently positions women as “adjacent” to the liberation struggle and not the full participants that they were and still are.

Herstories have been santised and packaged by men. The notion of a National Women’s Day highlights how the state has co-opted who and what women should be, and identified itself as the representative of women, not only in our daily lives but, very importantly, in the historical archives.

“Black women are the most erased and evicted of all people from the historical archives and official narratives of nation building, freedom fighting, colonialism, imperialism and officialdom. National liberation movements have introduced a toxic nationalism into our daily lives where women are often differentiated and excluded from a system that is, in effect, nothing more than a continuation of colonialism.” — Professor Patricia McFadden

Professor Patricia McFadden was the keynote speaker for this webinar. She is a radical ecological feminist or ecofeminist who lives a vegan lifestyle at her home on a piece of land in the mountains of eastern Eswatini, where she grows most of her food organically. She has been a feminist activist and writer for the past 40 years, and has published extensively on African States, African liberation struggles and radical feminist theory.

This is an excerpt by Professor McFadden from her presentation:

I have spent many years in the resistance circle of life and participated in the struggle in South Africa and our continent in all kinds of ways as a human living in a black female body. I have evolved into a radical ecofeminist because I feel the natural environment is the most important centre of activism for women that there is.

It offers us a door that we need to fling wide open, a door that will enable us to imagine and reimagine and recalibrate ourselves and our voices as we are today and who we are becoming.

There are so few spaces where we can be the beautiful women we are and that we dream of being. The natural environment is a vehicle through which we can create the space we need to flourish, and there is no more important space for us to occupy than the natural environment, on which all life depends. It is a space where women do not need to request men to recognise our roles and rights, but where we do this for ourselves and assert our rights from this critically important platform.

Why this conversation is so important is because it challenges neoliberalism and nationalism as discourses that function in very particular ways to silence women and all dissenting voices that challenge the status quo. Neoliberalism is driven by misogyny and wastefulness or what I call “wastism”; it is a system in which women’s voices and agencies have been muffled and erased, particularly when we critique the ideology of neoliberalism, nationalism and state power. As women, we need to recognise the deeply disabling impact of nationalism. Most of us draw our entire identity from nationalism, despite the fact that what nationalism has done is to reinvent feudalism, often at women’s expense.

Memory as it has been assembled thus far, and packaged as “history” is a political resource where history masquerades as “our story” and enables those who rule to claim a history of valour and foresight, and therefore to claim the right to exercise absolute power. When working people question the plunder of our resources they are reminded by the rulers that “we freed you and we have returned to rule you in an authentically African way, some of us are the sons and daughters of chiefs”; and if they are not the sons or daughters of chiefs, they install themselves as such, as if this is a legitimate system, when it is largely a system of terror and oppression of women.

The legendary 1996 Zimbabwean movie Flame was banned in Zimbabwe because it reflected the brutal truth of women’s experience in the liberation struggle in Zimbabwe. The state used its power to enforce sanitisation on the producers, directors and actors. Yet this was not an invention that crazy women conjured; it was the reality that we know, that we experienced in our liberation movements. The film is designed to recover and reinterpret history, and to remind us that there is no one history, there is herstory.

By claiming our own story, we change the meaning of memory and we awaken our radical consciousness, in a similar way to what Biko achieved with black consciousness. The majority of men are not interested in reading our work because they cannot truly recognise us and what we bring. Many men, including politicians and intellectuals, also try to speak about us, and it’s boring what men say about us: mostly they refer to us as some exotic additive, instead of as incredible contributors to the shift that came about as a result of liberation struggles, for which we still carry the violations in our bodies.

We owe it to ourselves to unmask patriarchy and misogyny on our own terms. We have to disrupt the notion of liberation movements as being a place of belonging for everyone. The significance of this moment is that it gives us the opportunity to unmemory the patriarchal version of ourselves, and retrieve and reinvigorate our own memories. This is a taking back of ourselves, beyond the reach of male narration; it is a doorway into a new and alternative way. We must not be silenced against the terror that continues to rage across our society. These moments serve to remind women that we are fierce, and when we do this, we return to ourselves.

“The manner in which the global system colonises all forms of life, including all forms of biodiversity, by placing ourselves above our life source — the natural environment — is a replication of how men colonise women in a hierarchical manner, and how white people colonise black people. This is a global issue and the Covid-19 pandemic is a real and true and indication of just how far away the human species has moved away from the natural environment on which we depend, as one of many species living on this amazing planet.” — Professor Patricia McFadden

I am happy to be able to say that I now live authentically in my own space, with myself as my autonomy. On my little piece of land I have found ways of maximising who Patricia is, what feeds me and what I can become. It’s time to create these new worlds of freedom for ourselves and for those with whom we want to share our futures. Systems of class, power and wealth have trapped too many women into establishing themselves as participants in the state. This is landmine territory and we cannot be radical in the state, it is a site, not of freedom, but of male-dominated, ruling class power, and we need to deeply understand this. From here, we need to grow the new feminist skin. I am still struggling from the bad habits of having been a feminist nationalist for most of my life.

Ecological feminism offers us the opportunity to change; to evolve the relationship between ourselves and the natural resources that sustain us, the powers of nature, the Earth’s kanga, which we wrap around our planet with its multitude of possibilities.

Today, every single day is a special gift that my life is giving to me and a pathway to freedom in this life. As an activist I have spent my life in search of freedom; I was always searching for the source of it, and when I found it in the relationship with nature, I gravitated towards it. It offered us the opportunity to return to the self, and there was no turning back. It was an embrace of the future and it is all around us if we simply turn to the extraordinary origins, memories, gifts and sensibilities that we as women have.

The Enigmatic Nosuthu Jotelo

Dr Nomathamsanqa Tisani

Dr Nomathamsanqa Tisani

This is an excerpt from the presentation by Dr Nomathamsanqa Tisani during the colloquium on African Women’s Intellectual Histories in August 2020.

The proverbial search for a needle in a haystack in the form of indigenous women in history is an agenda to be pursued relentlessly because banqabe njengezinyo lenkukhu.

This search is not just an exercise within what Meg Samuelson (University of Adelaide, Australia) refers to as ”the feminist idiom of global sisterhood”, nor is it within the black and white Western binary dance. What we are about is toppling the European medieval Great Chain of Being which located indigenous women at the lowest rung of the ladder, just above the chimpanzees and gorillas. Human history is all the poorer without the great histories of indigenous women.

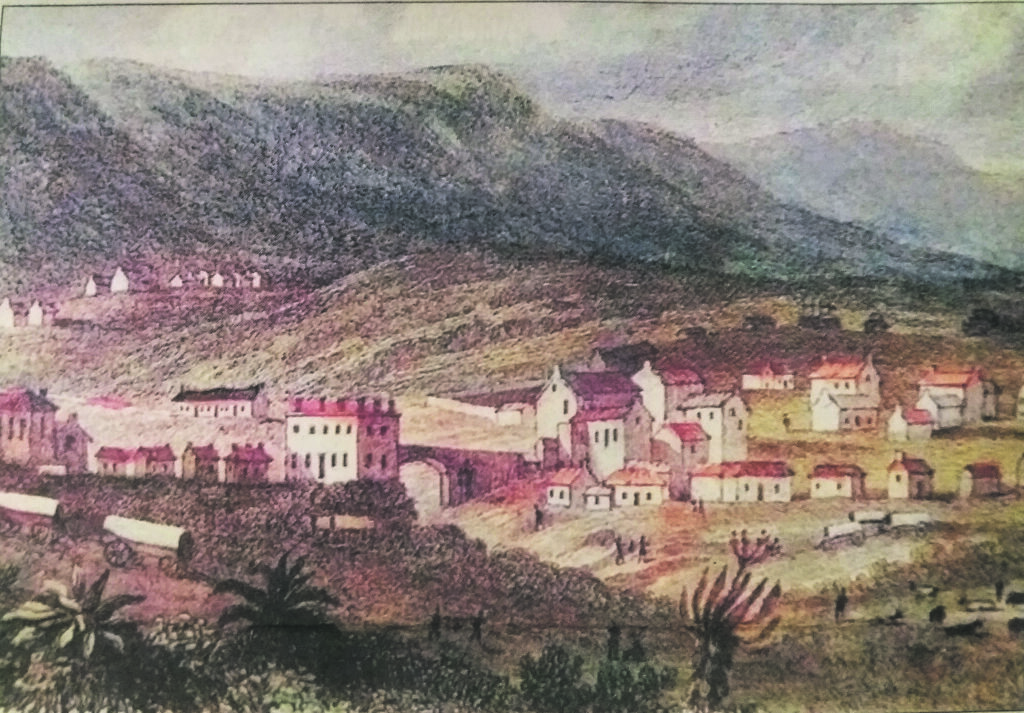

Artist’s impression of Bethelsdorp, the site of the oldest London Missionary Society (LMS) station in South Africa, which today forms part of Port Elizabeth

Artist’s impression of Bethelsdorp, the site of the oldest London Missionary Society (LMS) station in South Africa, which today forms part of Port ElizabethHere in southern Africa we have heroines about whom we vaguely have knowledge, such as Nzinga, MaNtantisi, Nandi, Mnkabayi, Suthu and many others. We are about the great restoration for which now is the time, Sekunjalo. A moment when we bring MamTshawe Nosuthu Jotelo — a 19th century isiXhosa speaking woman — back into human history and that of southern Africa. She deserves that honour, as you will hear.

Revisiting the life of an 19th century African woman necessitates a call to who she is even before exploring what transpired. Makhulu Nosuthu is MamTshawe of the Ntinde House, of Kote, of Tshatshu, of Ngconde of Malangana. Her socio-political profile is equally important and we can reconstruct it from her iziduko and those of amaJwara, the family she married into. MamTshawe, the royal princess, held a relatively senior position as she was married into amaJwara, Jotelo, Mtika, ndinganibizi ndinganilandanga. This clan is one of the old family lines within the social system of isiXhosa speaking people.

In 1804 Bethelsdorp included Xhosa and Gonaqua (people of Khoikhoi and Xhosa descent) converts to Christianity

In 1804 Bethelsdorp included Xhosa and Gonaqua (people of Khoikhoi and Xhosa descent) converts to ChristianityThis is one part of Nosuthu’s history. The other part is that her name first appeared in the missionary records during the 1830s as one of the women converts at Tyhume Mission Station of the Glasgow Mission Church. In addition to accepting the Christian faith Nosuthu embraced formal learning, going against prevailing norms and practices. Her eldest son, Festiri, attended school long enough for him to return and build a school with the help of Nosuthu. He, in turn, taught his mother and siblings, reading and writing — homeschooling indeed!

Nosuthu’s people have also been linked to Bethelsdorp, a London Missionary Society mission station from 1804 when Kote Tshatshu, inkosi of the amaNtinde took his young son to be educated by the missionaries. This Ntinde prince was given the name Jan or Dyani. Jan Tshatshu was baptised and steeped in Christian religion. Thus, Tshatshu, over a number of decades, is a prominent indigenous figure who appears in missionary, travellers and military journals. He was one of the best informed people at the time on both the African world as well as the fledgling European presence in southeast Africa. It is fair to consider Tshatshu as an early African intellectual.

In all likelihood, through her family, Nosuthu had been initiated into Christian teachings and issues related to formal learning by the time she married her husband. She would have brought novel thinking to her marital family as is expected of a bride — to come and imbue the children she would bear and the wider community with new ideas.

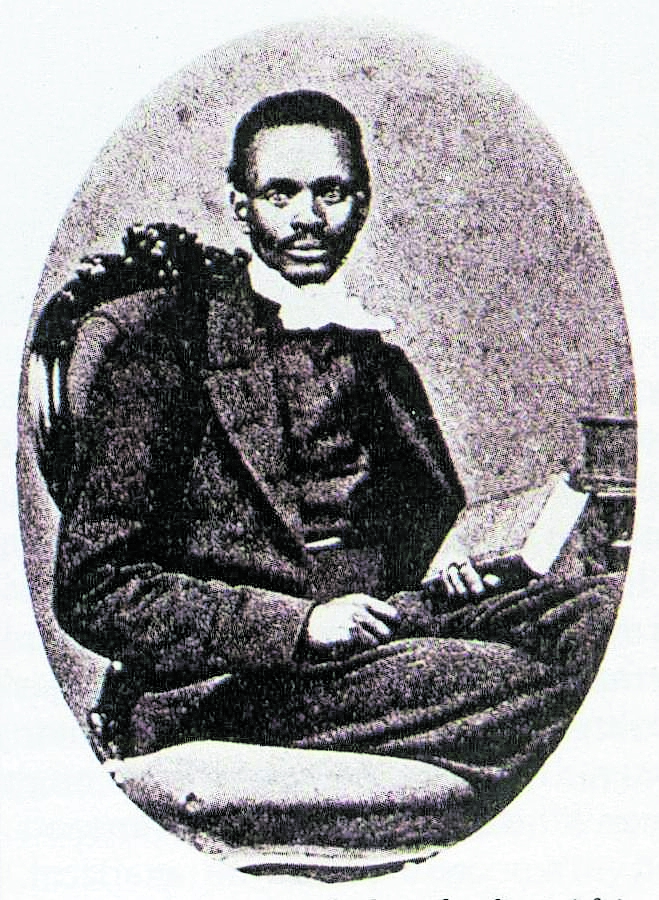

Nosuthu was thus a conduit through which both formal learning and Christianity were conferred to the Soga children and their children’s children, and the rest of South Africa. At the end of the 19th century the renowned Soga family dynasty was one of the most influential in the Eastern Cape. One of the sons, Tiyo Soga, was a prominent writer for Indaba newspaper, published between 1862 and 1865 at Lovedale. Soga was a pioneering literary figure in southern Africa and its most important missionary until his death in 1871. Indaba contributors were the vanguard of an “educated elite”.

Tiyo Soga – African nationalist politician of the Cape Colony

Tiyo Soga – African nationalist politician of the Cape ColonyIt can safely be stated that Nosuthu is the progenitor of the Soga Missionary and Intellectual Dynasty. The concept of ukufukama comes in here. While the verb ukufukama is associated with a chicken sitting on eggs, when it is applied to humans, then it covers the notion of nurturing, guiding, protecting and, above all, creating and brooding novel ideas. Nosuthu’s historical narrative is part of the rich tapestry of South African history.

About Dr Nomathansanqa Tisani

Dr Nomathansanqa Tisani is an historian and educator who has served in this capacity for 50 years, straddling secondary and higher education. Over the past five years Dr Tisani has been a visiting lecturer at Nelson Mandela University and her research has broken new ground on the history of African women during the 19th and 20th centuries. This has included work on outstanding figures such as Queen Mother Suthu, Sarah Baartman, MamTshawe Nosuthu Jotelo, Charlotte Maxeke, Nontetha Nkwenkwe and Lauretta Ngcobo.

In her work as a historian, she is a “keeper of memory”, much in the same breath as imbongi and wearing the mantle of uMakhulu and sharing stories of the family and clan. She is a member of the clans of amaTshawe and amaZotsho. She founded Eyethu Imbali, a history programme focused on the excavation and preservation of oral histories and stimulation of community history consciousness.

She cites the Church of the Province as a vital institution in her formation and Black Consciousness and Africanist thinking as key influences in her work. She is passionate about holistically supporting and mentoring girls and young adults in life generally and in their academic careers specifically.

Gender, Arts and Heritage: Contemporary Intellectual Histories

South African musician, Thandiswa Mazwai, who is known for lauding women who have shaped the woman that she is, during one of her performances.

South African musician, Thandiswa Mazwai, who is known for lauding women who have shaped the woman that she is, during one of her performances.

They have made their mark in the South African entertainment industry, entrenching their “womanism” through their artistic talent. They acknowledge, loudly and proudly so, the influence of various ordinary and extraordinary women — their grandmothers, mothers, aunts, sisters and fellow artists and peers — on their expressions of gender through the arts.

Actress and comedienne Celeste Ntuli and internationally renowned musician Thandiswa Mazwai shared their experiences as women in male-dominated spaces during their respective conversations with the Centre for Women and Gender Studies (CWGS) at Nelson Mandela University, in celebration of Heritage Month and the Centre’s first anniversary respectively.

Arts, culture and heritage were the focus of the Centre’s programme in September and October, as it continued its work to explore ways of thinking about how gender matters across different aspects of our lives.

“I grew up with the word ‘womanist’, and there was something about that particular framing that gave me the impetus to exist in the world without the baggage of gender. So, when I came into the Kwaito world, I came in as a young person who had lost the most valuable part of my life — my mother. So when I came into those spaces, I didn’t think that they were acting a particular way towards me, but that it was the way that things were,” said Mazwai, in conversation with Professor Pumla Dineo Gqola during the first anniversary virtual celebrations.

Mazwai is known for lauding influential women, such as the late Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Lebo Mathosa, Brenda Fassie and her own maternal lineage — who have shaped who she is today.

Actress and comedienne, Celeste Ntuli, has made her mark in the largely male dominated comedy space, using the stage to advance an African feminist agenda.

Actress and comedienne, Celeste Ntuli, has made her mark in the largely male dominated comedy space, using the stage to advance an African feminist agenda.

“Mam’ uWinnie, for me, has always represented that woman who bows to no one and doesn’t follow the rules, but makes her own. A woman who thrives, who fights, who is a celebration, who is dangerous and who is just naughty, beautiful, sexy and everything all in one. So, I was never going to let go of my lauding of Mam’ uWinnie Mandela because as I lauded her, I lauded every kind of woman that I was. She allowed me to say ‘I am what you say I am’,” said Mazwai.

Ntuli acknowledges her mother and aunts among the forces that shaped the woman she is, navigating the largely male-dominated South African comedy space with boldness.

“I am a woman, but first and foremost I’m a human being. My mom and aunts were dope people … they taught me that the definition of being a woman is non-defined — just be,” she said.

“As society, if we say that we are equal, then let us not box people. Let us let them be.”

The Centre, concerned with looking to the past for illumination on ways to better understand the present conditions of women, sought to explore, through intergenerational dialogues, how gender shapes what is remembered and recognised, and what this means for the intellectual, creative and activist energies of African women.

With the deliberate focus on gender, arts and heritage, and through these conversations, the Centre sought to take time to study the work of prominent figures in popular contemporary arts, such as Mazwai and Ntuli, who explore women’s gender diversities through their artistic expressions.

Other women performing artists, whose contribution to history and contemporary discourse was shared through presentations during the two-day Inyathi ibuzwa kwabaphambili: African Women’s Intellectual Histories colloquium hosted by the Centre at the end of August, include:

Zenzile Miriam Makeba, whose life and work reflects, according to jazz vocalist and scholar Nomfundo Xaluva, the profound complexity of a black woman’s journey and place in the world.

“To confine her legacy solely to her music is to censor her significant contribution to the liberation struggle and her indelible mark in the creative and cultural heritage of the African continent,” said Xaluva, who presented a paper titled Zenzile Miriam Makeba: A Legacy Hiding in Plain Sight.

Lebo Mathosa and her awareness of the gendered norms within the various genres she incorporated in her art.

“The aim for my paper [was] to explore how genre influences Mathosa’s performance of gender and how she expresses her sexual agency visually, musically and lyrically,” said Thulisile Msezane in Lebo Mathosa: Genre as a Compass for Gender Performance.

Resisting the erasure of black women’s intellectual tradition

By Dr Athambile Masola, writer, researcher and teacher at the University of Pretoria (nGAP lecturer)

“Ukuzilanda refers to a practice of fetching oneself in order to connect the past to the present … [It] echoes the proverb ‘inyathi ibuzwa kwabaphambili’ (wisdom is learned from the elders). The important word in this proverb for me is ibuzwa — the practice of interrogation, which is also at the heart of ukuzilanda and requires us to ask questions in order to get the answers we need about the ways in which erasure happens.” Dr Athambile Masola

Growing up, umama insisted I know isiXhosa, my mother tongue. She ensured I was exposed to isiXhosa, through radio and the stories of Gcina Mhlophe, to sermons and Bible readings in church.

With my mother having prepared the soil for me to take black tradition seriously, my friends introduced me to a practice of sharing books and introducing me to feminist writers and researchers. My friends and mentors have been the stewards of my intellectual journey, as they shared writings of black women whose feminist imagination challenged me to understand the effects of the Eurocentric education I had received for 12 years at a prestigious girls’ school.

Writer, researcher and teacher at the University of Pretoria (nGAP lecturer), Dr Athambile Masola

Writer, researcher and teacher at the University of Pretoria (nGAP lecturer), Dr Athambile Masola

This practice of sharing exposed me to Noni Jabavu’s memoirs. Reading The Ochre People and Drawn in Colour together with Sisonke Msimang’s Always Another Country led me to the idea of ukuzilanda, which I incorporated into my doctoral research. Ukuzilanda refers to a practice of fetching oneself in order to connect the past to the present. An example of this among some cultures is the recitation of family names (ukuzithutha) for ritual purposes and to connect to the past. In a sense, ukuzilanda echoes the proverb “Inyathi ibuzwa kwabaphambili”; wisdom is learned from the elders. The important word in this proverb for me is ibuzwa: the practice of interrogation, which is also at the heart of ukuzilanda and requires us to ask questions in order to get the answers we need about the ways in which erasure happens.

The importance of ukuzilanda becomes apparent when we read the ways in which history has been constructed. One of the ways in which South Africa’s African nationalism movement has been constructed is through the emergence of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) in 1912. Charlotte Maxeke was the only woman in attendance at the meeting in Bloemfontein. What has often been omitted was the response of the women’s organisation, which had already begun with pass protests in 1903. An example of this can be found in the poetry of Nontsizi Mgqwetho and the newspaper archive, which tells a different story about women’s work in the early 20th century.

In 1918 Maxeke established the Bantu Women’s League (BWL), which has recently been co-opted as the precursor to the ANC Women’s League without a thorough examination of the evidence which exists, suggesting a different narrative. When I read Mgqwetho’s poetry alongside Maxeke’s open letter published on 12 June 1920, we see that Maxeke was not merely an attendee at the SANNC’s inaugural meeting, but rather someone who lambasted the Congress for the fractures they had in their organisation, which had consequences for the BWL. I read and analysed her letter alongside Mgqwetho’s poem Uqhekeko lweCongress (The split of Congress), which echoes Maxeke’s concerns. Without the voices of these women as part of our understanding of African nationalism in South Africa, we have an incomplete picture of the contestations during their time, which have implications for how we understand politics today.

This work of rereading history while looking for the names of women is a long tradition firmly established by African feminists. Together with Maxeke and Mgqwetho’s writing in the early newspapers, the publication of the Women Writing Africa series is a response to the erasure of women’s writing across the continent. This series of anthologies is the most extensive archive available because of the thorough work of African feminists from all regions of the continent—southern, northern, eastern and western and Sahel — which has evidence of women’s writing translated into English dating as far back as 6th century BC in Egypt.

This anthology series answers the questions Boitumelo Mofokeng posed in 1989 —“where are the women?” — in response to Staffrider magazine’s commemorative issue, published in 1988 to celebrate 10 years of its existence. The issue only included three writers, thus leaving out many of the women who had contributed poetry to the magazine from as early as 1979. This question continues to find resonance, as it challenges the ways in which we think about the representation of black women in the public sphere, and the ways in which their intellectual contributions are included.

A Doctor Displaced: Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma’s Time in Exile (1976-1990)

Dr Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma. (Photo: Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Dr Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma. (Photo: Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

In November 2015, Nica Cornell chose Dr Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma as the subject of her final submission for an honours course. Dr Dlamini-Zuma’s name had been tossed around in the media as a possible presidential candidate. At the time, she was the Chairperson of the African Union Commission — the first woman to hold this post.

“I quite vividly remember going to the library, with the naïve assumption that there would be a few books I could use. There weren’t any. That void sent me on a five-year journey — from South Africa to England, and back to the archives at the University of Fort Hare,” said Cornell, giving her presentation at the Inyathi Ibizwa kwabaphambili coloquium.