Thirsty: Xhosa initiates in Coffee Bay near Mthatha are at risk of dehydration in summer unless cultural practices can adapt to new ecological realities. (Mujahid Safodien/ AFP)

Eleven deaths have already been recorded since the beginning of the summer initiation season late last year. Like most initiation seasons, the most common causes of death are complications from infections —or dehydration. The Eastern Cape’s MEC for cooperative governance and traditional affairs, Fikile Xasa, has previously called on parents to avoid summer initiation schools when temperatures soar and dehydration risks increase.

Data on the causes of death for every initiation season is not readily accessible, and there is room for studies to explore a correlation between record hot summers and increasing chances of death by dehydration. However, depriving initiates of water is a critical part of the ritual.

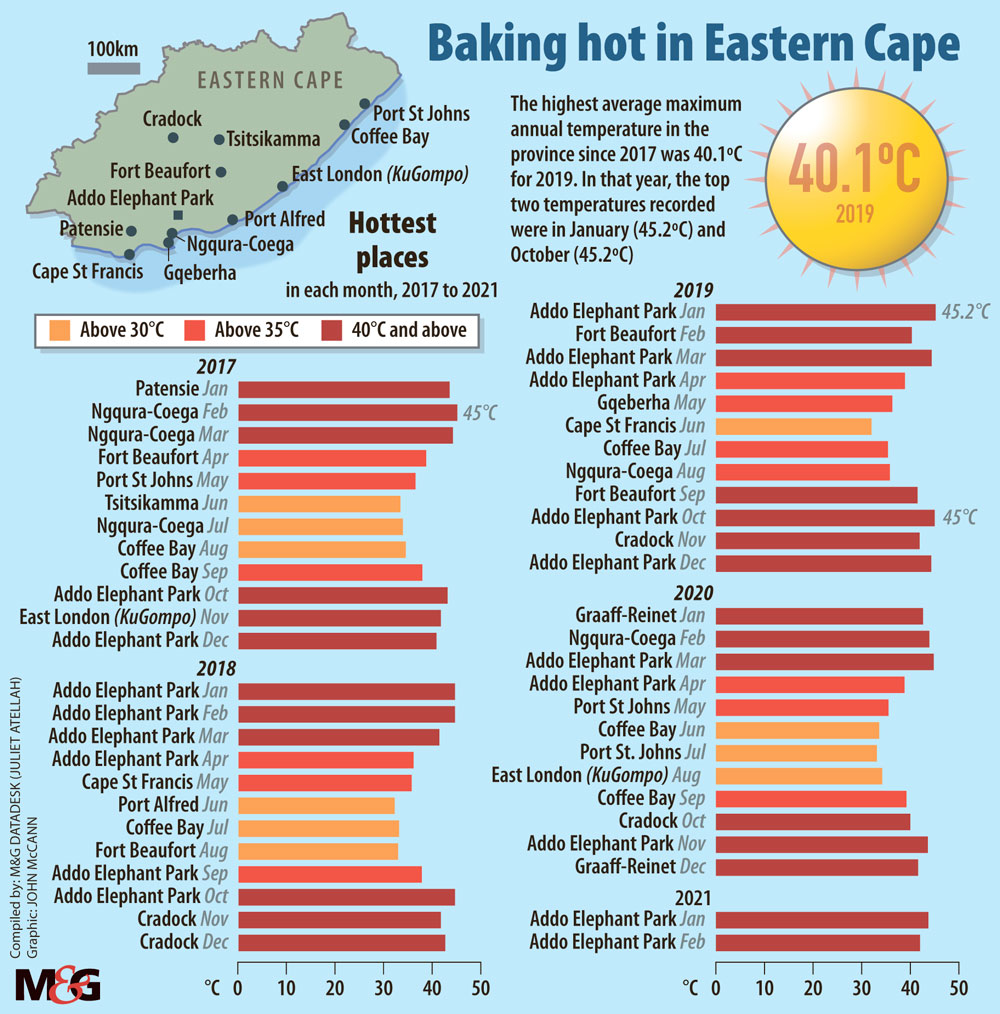

Weather data is increasingly reflecting what scientists have been warning since Eunice Foote first demonstrated the heating effects of greenhouse gases in 1856. The planet is warming, summers are hotter and weather extremes more frequent.

South Africa is no exception. Last year Gqeberha (formerly Port Elizabeth) nearly beat its 1965 record temperature of 40.7°C when the mercury hit 40.2°C.

“[The city] recorded one of the hottest Junes on record. In fact the average maximum temperature of 22.5°C was an all-time record since records started in 1950,” said Garth Sampson at the South African Weather Service in the Eastern Cape. “It surpassed the record of 22.1°C, which was recorded in 1996. This is almost a full two degrees higher than the average of 20.7°C. East London also recorded a record high average maximum temperature of 24.1°C, which was also the highest since 1950,” he added.

The international nonprofit organisation USAid said: “Across the country, mean annual temperatures have increased at least 1.5 times the observed global average increase of 0.65°C during the last 50 years. The probability of austral summer heat waves over South Africa increased over the last two decades of the 20th century compared to 1961 to 1980.”

This means that depriving initiates of water after circumcision could spell disaster for the thousands of boys who are bound for the mountains in future summers.

If summers are characterised by record temperatures for the foreseeable future, what does this mean for the survival rate of initiates who volunteer to go without much water for several days?

The World Health Organisation (WHO) characterises heat waves as one of the most dangerous of natural hazards. Between 1988 and 2017, WHO said that 166 000 people died due to extreme temperatures, while in 2015 the number of people exposed to heat waves increased by 175-million across the globe.

Manhood rituals take place across South Africa’s provinces twice a year (once in winter and again in summer), with circumcision rituals varying among the cultures that practice it.

Parents and guardians wave nervously as abakhwetha (initiates) are escorted onto the mountain (entabeni or komeng) where they will face physical and mental challenges. Those who survive will bury the remnants of their life as boys and emerge proudly as men. Ukuwela/howela, or crossing over, means shedding the old self and embracing the adult world, worthy of privileges, titles and respect not afforded to those who fail the ultimate test of manhood.

According to a 2017 report into initiation deaths the cultural, religious and linguistic rights commission (CRL) said: “Some people regard this sacred custom, this rite of spiritual orientation (performed in temples disparagingly called: The School in the Bush or the Mountains) as ‘the shrine of a people’s soul’. It is an occasion in which the initiates esoterically reignite the spiritual consciousness of the male person. Thus, the sacredness of this process of ritual purification (ukukhothwa ubuNqambi) remains inviolate regardless of whether it’s done collectively or not.”

A 2009 case report in the Journal of Transcultural Nursing said traditional circumcision was seen as a sacred religious practice.

The custom is strongly associated with identity, and defines a man’s status within his community for the rest of his life. According to the authors, significant stigma is attached both to failed initiates and uninitiated people. In the Eastern Cape, the important coming-of-age ritual for amaXhosa remains embedded in the adage of “survival of the fittest”.

“Boys have to be successfully initiated to marry, inherit property or participate in cultural activities such as offering sacrifices and community discussions,” reported a 2010 study in the journal Qualitative Health Research. “If they are not circumcised, they are given leftover food at celebrations, are not allowed to socialise in taverns with other men, are not allowed to use the family name to introduce themselves and are sometimes forcefully taken away from their girlfriends.”

Culture and traditions change over time as people adapt to changing environments, and ulwaluko (initiation) is no different.

Despite victimisation and stigma associated with the ways in which a boy transitions to manhood, many families are choosing to support initiation schools that provide water and guarantee sterile tools are used in the circumcision.

In 2010 researchers studied complications of traditional circumcision in the Eastern Cape. The findings included sepsis (56.2%), genital mutilation (26.7%), dehydration (11.4%) and amputation of genitalia (5.7%).

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

The public hearings on the challenges and problems of male initiation in 2017 culminated in a final report that was expected to initiate corrective action to address the increasing risks of fatalities during the male circumcision ritual.

Public hearings were held in several provinces where the custom is practised. In the final report, the CLR highlighted that initiation practices are universally common to many cultures across the world.

“They come in many forms and institutional expressions. They are historical indicators used by human communities to mark the transit from one stage of life to another,” it said. The report goes on to recommend that the custom adapt to a changing environment and society.

“Even though the practice has survived the passage of time, it is faced with the need for some modernisation and its attendant challenges. Initiation’s resilience is being tested against its capacity to adjust to and accommodate these modern tendencies, while simultaneously finding its rightful place and expression. Beyond that, today, male initiation faces the challenge of a public outcry about its various problems.”

The investigation found that the Eastern Cape had the highest prevalence of initiates (average 79%) within the three-year period (2014 to 2016) compared to the other provinces, which had averages of 5% or less. The CLR noted that the longer and hotter summer initiation season negatively affects the healing process of the wounds of initiates.

The spokesperson for the Eastern Cape department of traditional affairs, Mamkeli Ngam, told the Mail & Guardian that parents, families and the public are encouraged to put the safety of their children first. The South African constitution recognises the right to religious and cultural freedom, but acknowledges that the death rate during initiation seasons have become a national health concern.

The department said that it is the responsibility of parents to ensure that the initiation schools of their choice are giving abakhwetha water to avoid dehydration and death, in spite of the traditional voluntary deprivation of water being an important aspect of the tradition.

Studies are increasingly exploring the effect climate change may have on traditional norms and customs. Professor Christian Nche George at the department of religion and cultural studies at the University of Nigeria noted in a paper published by the Journal of Earth Science & Climatic Change: “African traditional leaders should lead their respective affected communities to embrace and adjust to the changes in the global climate and resultant ecological realities.

“The African traditional religious practitioners should be made to understand the dangers of climate change as well as their roles in mitigating these dangers,” the paper said.

Tunicia Phillips is an Adamela Trust climate and economic justice reporting fellow, funded by the Open Society Foundation for South Africa