Drought equaliser: Cape Town residents queued to refill water bottles at Newlands Spring. This may soon be Gauteng's future. (Morgana Wingard/Getty Images)

Gauteng faces the possibility of Day Zero in the next 10 to 20 years as long droughts caused by the climate crisis batter the country, a lead author on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned.

Francois Engelbrecht, a professor of climatology at the Global Change Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand, was unpacking the implications for South Africa and the Southern African region of the findings of a definitive new IPPC report on the physical science basis for climate change, on which he was a lead author.

For the nearly 4000-page report, 234 climate scientists, including several local experts, assessed 14 000 peer-reviewed studies, concluding that it is “unequivocal” that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land.

The scale of recent changes across the climate system are “unprecedented” over many centuries to thousands of years. These emissions are human-driven and responsible for about 1.1°C of warming since pre-industrial levels.

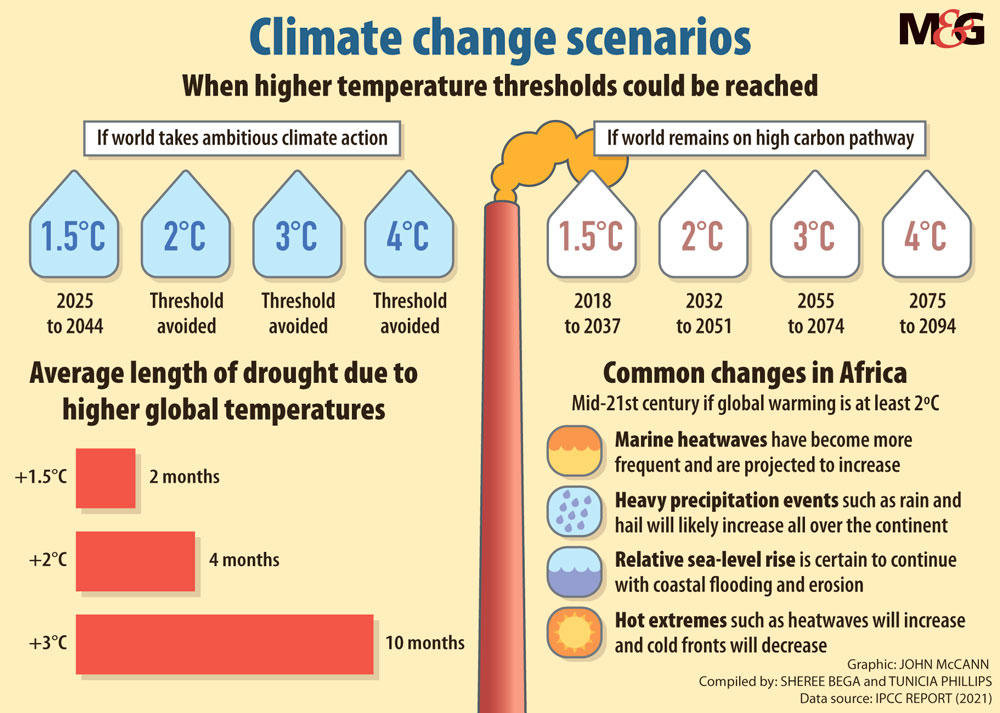

Averaged over the next 20 years, global temperature is expected to reach or exceed 1.5°C.

Southern Africa, a hot and dry region that is already water-stressed, is projected to become drier and warmer, leaving limited options for adaptation.

Alluding to how Cape Town nearly ran out of potable water in 2018, Engelbrecht said a Day Zero drought for Gauteng was the single biggest of four climate risks South Africa faced in the near term.

“This report tells us that droughts are becoming more likely in Southern Africa as the level of global warming increases. Just think what it will mean if the mega dams in eastern South Africa become so low in terms of their dam levels that they cannot fully supply Gauteng with the water supply it needs for the Gauteng industries and households?

“Let us be extremely careful about what this risk may mean in terms of economic impact and social unrest if we run out of water for large periods of time in the province … I don’t think we are prepared in any way.”

Gauteng has already come close to such an event but “too few people realise that”, Engelbrecht said, referring to the 2015-16 El Nino drought when the Vaal Dam fell to below 25% in September 2016.

“If you speak to water engineers, to people concerned about water quality, colleagues at Rand Water, they will tell you that should the level of the dam fall to below 20% then the Gauteng supply is compromised for water quality reasons and for engineering reasons in terms of pumping the water uphill towards to Johannesburg, for example.

“In a world that becomes drastically warmer with more evaporation, with more of these droughts that we’ve been seeing in the last decade in South Africa that last three to five years, that risk is increasing,” he added.

The second risk is to the agricultural sector. The 2018 IPCC Special Report on 1.5°C found that the maize crop and cattle industry may collapse at 3°C of global warming, which means about 6°C of regional warming. “Can we maybe reach the tipping point at 2°C of global warming because sustainable agriculture is not only about the biophysical impacts of heat waves and drought, it’s also about socioeconomic aspects. For how long can a farmer keep on farming when there’s three years of drought, then four and five years … There is evidence documented in the report of observed increases in drought across this region that we can already detect.”

The third risk is the direct effect of prolonged, unprecedented heat waves on human mortality, he said, citing how hundreds of people died in the unprecedented heat wave in the Pacific Northwest in early June.

“It can happen in South Africa and it has. It’s just that our data is not so good in terms of detecting mortality induced by heat waves in our region.”

The fourth risk, for which South Africa “is not prepared for at all”, is the possibility of intense tropical cyclones moving southwards, affecting Maputo (Mozambique) and the Limpopo River Valley between South Africa and Zimbabwe, Engelbrecht said.

“It’s even possible that such a cyclone can reach Richards Bay. Just think about the immense impact it can have in terms of loss of life and also on the economy. The report is very clear that increases in intense tropical cyclones can already be detected across the world with the risk extending to Southern Africa,” he said, citing Cyclone Idai in March 2019.

The report also shows how the frontal systems that bring South Africa its winter rainfall are increasingly being shifted towards the South Pole as the planet warms, leaving cities like Cape Town increasingly vulnerable to drought.

“The cold fronts that are so important for our winter rainfall will find it increasingly difficult to reach the southern parts of South Africa in a warmer world,” Engelbrecht said.

South Africa is warming at twice the global rate.

Climate change, to a large extent, is about the changes in extremes. “What the report indicates very clearly is that with every 0.5°C of warming there are clear increases in the intensity and frequency of a large number of different extreme event types,” said Engelbrecht.

Many changes in the climate system become larger in direct relation to increasing global warming, according to the IPCC report. These include increases in the frequency and intensity of hot extremes, marine heat waves, and heavy precipitation, agricultural and ecological droughts in some regions, and proportion of intense tropical cyclones, as well as reductions in Arctic sea ice, snow cover and permafrost.

Some changes are “irreversible” for centuries to millennia, especially in the ocean, ice sheets and global sea level.

But a key finding is that limiting warming to 1.5°C is “still within our reach”, said Pedro Monteiro, chief oceanographer at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research and a lead author of the IPCC report.

“Climate change is widespread, it’s everywhere, it’s human-driven unequivocally, it’s rapid and it’s accelerating and intensifying. Slowing or stopping this process requires strong, rapid and sustained greenhouse gas reductions.”

Either way, the world is going to change, Engelbrecht said. “Let’s keep our eye on COP26. If that new climate pact forms and we see these investments in renewables shooting up at levels never seen before, the world will change fast and South Africa will have to have all its ducks in a row to keep pace because the world will expect us to completely change our dependence on coal within decades. There will be substantial support under such a treaty for us to make this transition.”

But if it fails, the world will also change, he warned. “Then it will be extremely likely we will exceed these dangerous levels of global warming and South Africa will have to increasingly focus on adaptation measures.”