South Africa lacks a detailed, long-term national system of data collection on dust storms

On 16 October 2014, a large dust storm swept across South Africa. It originated in the Northern Cape where strong winds occurred as a dry thunderstorm built up.

High wind speeds in the Free State caused the soil to lift from large areas of dry, open farmland, forming a “wall” of dust that swept through Gauteng and the North West, wrote Angela Mathee and Vusumusi Nkosi of the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) in a 2022 article on dust storms in South Africa, which was published in the journal Quest.

At the time of the 2014 dust storm, Eurostat, Europe’s meteorological satellite agency, noted how dust storms are rare events in South Africa and that one which travelled more than 800km across the country was even more uncommon. The event, it said, “left residents running to close windows and doors after they realised that ‘that big dust cloud’ is actually about to move over them”.

Under-appreciated, more frequent

This week, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) warned that sand and dust storms are an under-appreciated problem that is now “dramatically” more frequent in some parts of the world. At least 25% of the phenomenon is attributed to human activities.

With impacts far beyond the source regions, an estimated 2 billion tonnes of sand and dust now enter the atmosphere every year, an amount equal in weight to 350 Great Pyramids of Giza. In some areas, desert dust has doubled in the last century, increasing the chance of sand and dust storms.

“The sight of rolling dark clouds of sand and dust engulfing everything in their path and turning day into night is one of nature’s most intimidating spectacles,” said Ibrahim Thiaw, the executive secretary of the UNCCD, in a statement. “It is a costly phenomenon that wreaks havoc everywhere from Northern and Central Asia to sub-Saharan Africa.”

Sand and dust storms presented a formidable challenge to achieving sustainable development. “However, just as sand and dust storms are exacerbated by human activities, they can also be reduced through human actions,” he said.

Solid walls of dust

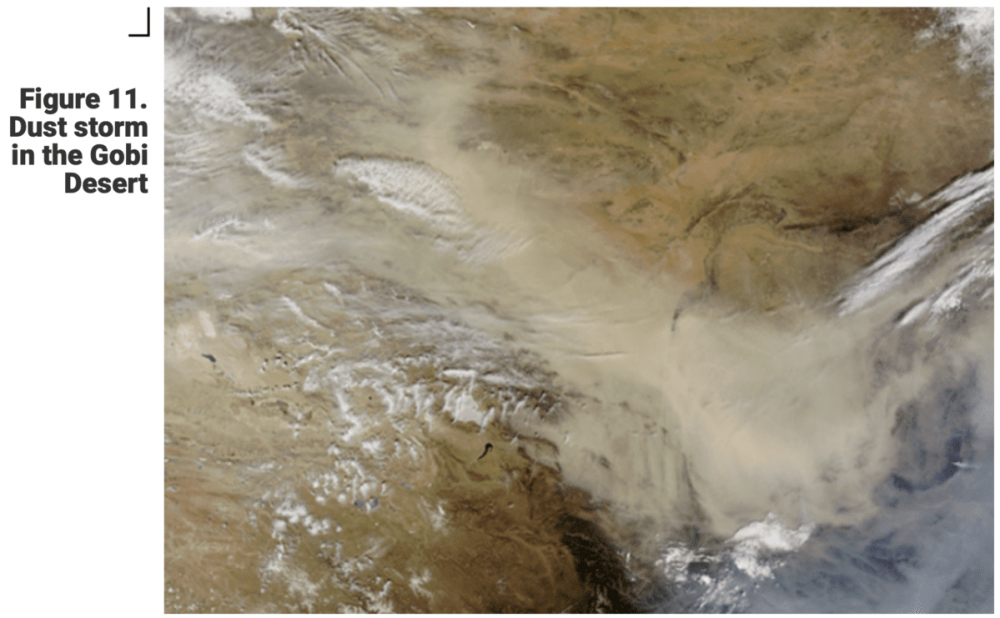

Major dust storms, the “front edges of which may span tens of kilometres and pass over great distances”, are well known across the world, including in Africa, Asia and America, wrote Mathee, the chief specialist scientist at the SAMRC’s environment and health research unit, and Nkosi, a senior scientist in the unit.

“Often described as a ‘solid wall of dust’, dust storms have wreaked havoc with agricultural land, caused immense damage to property, worsened air quality, disturbed road and air transportation and caused harmful health impacts, even loss of life.”

Dust storms have been associated with both natural factors, such as precipitation and wind strength, and human factors such as poor agricultural practices. Mathee and Nkosi also said there is growing concern that changing climate could be causing an increase in the frequency, intensity and distribution of major dust storms

There is a need to explain the implications of dust storms and share preventative measures to protect human health by increasing awareness. The authors drew on international and local information about dust storms and developed a public information sheet for South Africans.

Range of health effects

The health consequences of dust storms are a serious concern, they said. “For example, exposure to dust storms has been associated with skin and eye irritation, decreased lung function, increased cardiovascular effects, increased hospital visits and admissions and more frequent use of emergency services.

“In the longer term, for people exposed to many dust storms over many years, there have also been associations with adverse pregnancy outcomes and birth problems. Children, neonates, the elderly, pregnant women and people with chronic cardiopulmonary diseases have been shown to be particularly vulnerable to the health consequences of dust storms.”

But in South Africa, there is limited information available on dust storm patterns, with a key reason being the lack of a detailed, long-term national system of data collection on dust storms, the authors said.

“This database is needed to assess changes in the frequency, severity and distributions of dust storms in the country. From sources of information like anecdotal accounts and satellite imagery, there is evidence that major dust storms do occur in South Africa from time to time.”

For example, satellite imagery showed an increase in dust storms in the Free State between 2006 and 2016.

“The South African Weather Service reported large dust storms that swept across most parts of the country in October 2014 and January 2016. Dust plumes that ‘turned skies red’ in Alexander Bay (Northern Cape) during September 2019 were also visible from satellite images.”

Information about when and where dust storms occur is needed but at the same time data about how dust storms affect human health is also needed. After dust storms passed over Kimberley in 2014 and 2016, the SAMRC conducted a pilot study looking at the impacts on health, “however, the information in the study (as yet unpublished) is limited, and considerably more research is needed to fully understand how dust storms affect health in South Africa”.

Unpredictable and dangerous

While dust storms are a regionally common and seasonal natural phenomenon, the problem is worsened by poor land and water management, droughts and climate change. And fluctuations in their intensity, magnitude and duration “can make sand and dust storms unpredictable and dangerous”, the UNCCD said.

The major global sources of mineral dust are across North Africa, the Middle East and East Asia, Australia, South America and Southern Africa. According to the UNCCD, more than 80% of Central Asia is covered by deserts and steppes, which “coupled with climate change and lasting droughts represent a major natural source of sand and dust storms”.

“The dried up Aral Sea [in Central Asia] is a major source of sand and dust storms, emitting more than 100 million tonnes of dust and poisonous salts every year”, which affects “not only the health of people living in the vicinity, but far beyond” and generates annual losses of $44 million.

Sand and dust storms cost the oil sector in Kuwait an estimated $190 million annually, while a single sand and dust storm event in 2009 resulted in up to $243 million in damage in Australia. And while some places benefit from this nutrient deposition on land, and mineral and nutrient deposition on water, particularly ocean bodies, “these limited benefits, however, are far outweighed by the harms done”.

“Sand and dust storms have become increasingly frequent and severe having substantial transboundary impacts, affecting various aspects of the environment, climate, health, agriculture, livelihoods and the socioeconomic well-being of individuals,” said Feras Ziadat, technical officer at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation and the chairperson of the United Nations Coalition on Combating Sand and Dust Storms.

“In source areas, they damage crops, affect livestock and strip topsoil. In depositional areas atmospheric dust, especially in combination with local industrial pollution, can cause or worsen human health problems such as respiratory diseases.

“Communications, power generation, transportation and supply chains can also be disrupted by low visibility and dust-induced mechanical failures.”

UNCCD experts said that unified and coherent global and regional policy responses are needed to address “source mitigation, early-warning systems and monitoring”.