South Africa needs to change its top-down approach, consult communities and fast track the delayed Integrated Energy Plan

The conclusion of the 28th iteration of the United Nations Climate Change Conference further cemented the need to bolster institutional quality and build strong resource governance mechanisms to adapt to the climate crisis and ensure energy justice for all.

For this to be fully realised, an adoption of simplified approaches must be considered to deliver inclusive climate action.

For a just energy transition (JET) to successfully materialise, concentration should be on localising JET. Understanding public perceptions and affording people greater climate awareness while learning from those on the front line will be essential for a realistic transition. But what does it mean to have a JET that fully integrates public perceptions to ensure it delivers on its objectives?

Ongoing debates about what a just energy transition means, and who it is “just” for, have percolated discussions at the various Conferences of the Parties and continue to gain traction as the world shifts to greener sources of energy provision. Globally the movement is multi-layered, with varied understandings and approaches that are driven by various actors and institutions.

Africa’s position on the transition is no different — multi-layered and complex. In July last year, the African Union adopted a common position on energy access and a just transition that provides a “comprehensive approach for Africa’s short, medium and long-term energy pathways to accelerate universal energy access and transition without compromising its development imperatives”.

The common position stipulates that Africa will continue to use all forms of its abundant energy resources including renewable and non-renewable energy to address its needs.

With this understanding, definitional clarity and transition pathways should be provided and owned by respective countries — in developed and developing contexts.

Access to energy is significantly lower in Africa compared with other regions.

About 567 million people are without electricity (the lowest access in the world) where, according to the 2021 ND-GAIN Country Index, seven out of 10 most vulnerable countries are in Africa.

And although Africa only emits about 4% of global carbon emissions, it loses $7 billion and $15 billion a year because of the effects of climate change. By contrast, 23 developed countries such as Canada, Germany, Japan, the United States and large parts of Europe have contributed about 50% of global greenhouse gas emissions over the past century.

China alone is responsible for nearly 14% of the global greenhouse gases, making it the world’s single largest emitter.

Although there is a vast gap between carbon emission contributions, the effects and consequences are more severe in Africa. These realities are indicative of an unjust international system.

COP28 had the potential to effectively address climate change consequences but the aim is to actualise commitments made and to decentralise decisions and agreements. One way of doing this is by not only mapping out practical ways of achieving targets but by also adopting people-centred policies that reflect domestic understanding of and commitments to climate change.

In taking public perceptions of climate change into consideration, we can assess an underexplored measurement of the effectiveness of the Conferences of the Parties — public perceptions.

World leaders gather annually, at great cost (climate-wise and monetarily) to make important decisions, but to what extent are these decisions and agreements relevant and beneficial to the people of Africa? On acknowledging that the “just” in the JET is largely about the people, how do they understand climate change? Do agreed decisions translate to a greater sense of agency and awareness?

Climate change has devastating effects on people’s lives, and the human cost is expected to rise in the coming decades. Therefore, it is critical to adopt coordinated interventions from businesses, governments, civil society and the public.

Global agreements made at COP28 need to translate to increased domestic capabilities, and the buy-in of the people and political leaders — but this depends on their awareness of climate change, a sense of agency, and public understanding of climate risk.

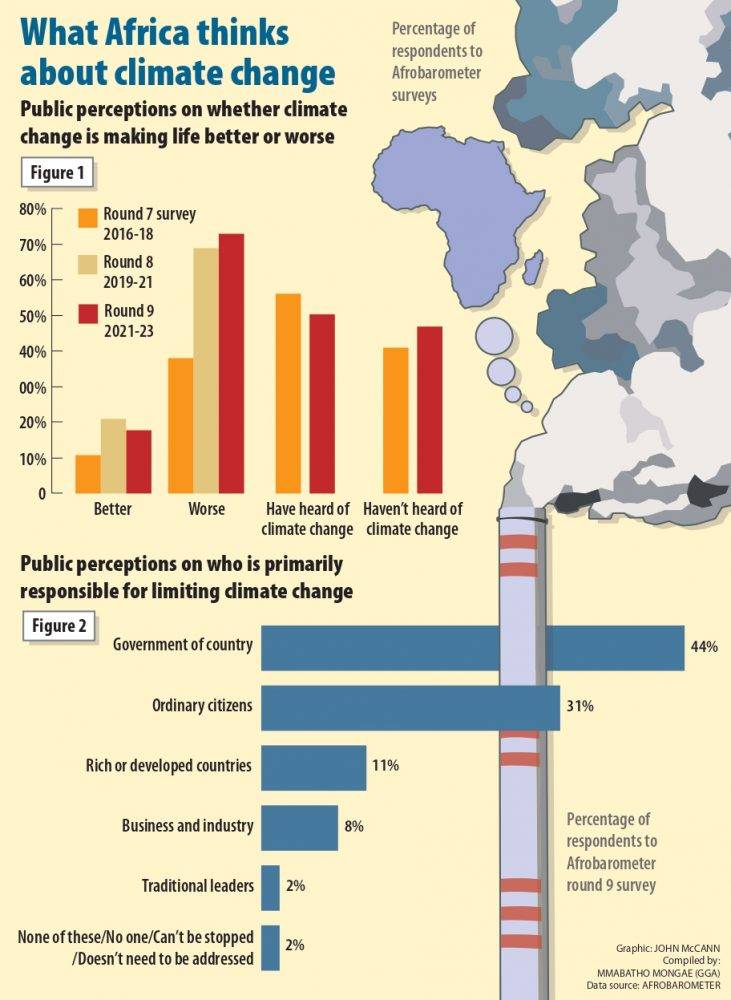

According to the Afrobarometer round 9 survey, more Africans say that over the past 10 years, droughts and floods have been more severe. When asked if they have heard about climate change, 50% of African respondents say they have heard of it.

Surprisingly, from 2016 (round 7) to 2023 (round 9) there is a six-point decrease in the number of Africans who have heard of climate change.

This decrease may be indicative of several factors which include a language barrier, the decrease in the percentage of respondents surveyed or population growth. On the converse, there is a six-point increase in those that have not heard of climate change.

Although there is a decrease in those that have heard of climate change, more Africans perceive climate change to be getting worse. From 2016 to 2023 there has been a 35 percentage-point increase in those that perceive climate change to be getting worse.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

Of perhaps greater interest is those who perceive climate change to be getting better. From 2016 to 2018, 11% of Africans said climate is improving; this increased to 21% from 2019 to 2021, and slightly decreased to 18% from 2021 to 2023. This perception is particularly high in Sudan (25%), Mozambique (17%), Sao Tome and Principe (16%) and Namibia (13%).

The Afrobarometer rounds 7, 8 and 9 coincided with COP22 (2016) to COP28 (2023). Within this eight-year period important and ground-breaking decisions were made but there appears to be a gap between these decisions and the decentralisation of knowledge.

These trends indicate several factors that may include language barriers and the lack of education and initiatives on climate change. For the former, people may not be aware of the term “climate change” but may be able to describe what it is, nonetheless.

These are complexities that should be considered at COP28. Buzz words at COP28 (and previous Conferences of the Parties) include: climate adaptation, loss and damage fund, climate resilience, and renewable energy, but how will world leaders make this language intelligible at the ground level?

Climate change is a global issue and requires a coordinated global response — including a greater sense of agency from people.

Despite decreases in the number of Africans who have heard of climate change and an increase in those who say climate change is making life better in their country, there is a significant sense of agency from Africans. When asked: Who is primarily responsible for limiting climate change, 44% of Africans say that it is primarily the government’s responsibility to limit climate change. This is followed by 31% of Africans who say they are primarily responsible for limiting climate change.

This coincides with 86% of Africans who think that people need to do more to limit climate change. This finding is encouraging and suggests that African residents are willing to do something about climate change.

Interestingly, only 11% of Africans say that rich or developed countries are primarily responsible and fewer say that business and industry is responsible. This is indicative of a sense of ownership and agency among Africa’s citizens.

In dealing with climate change, the focus should be less on processes and rather prioritise agreeing and adopting practical and binding measures that reflect the realities and perceptions of Africans.

COP28 and future Conferences of the Parties long-term effectiveness will be in the ability to simplify decisions and agreements that bridge the gap between high-level decision-makers and people’s understanding.

Busisipho Siyobi is the lead researcher in the natural resource governance programme at Good Governance Africa. Mmabatho Mongae is a data analyst in the

Governance Insights and Analytics Programme at Good Governance Africa.