Taking a leaf out of Unesco’s textbook: The Execs Back to School event at Yeoville Boys’ Primary School shows how successful public and private sector collaborations can be.

The recently published UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco) report Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education, calls for an overhaul of the education system worldwide.

The report highlights the need to transform education models, arguing that they are outdated and failing to meet the demands of our rapidly changing world.

At the core of Unesco’s vision is an emphasis on inclusive, equitable and sustainable education, which underscores the importance of lifelong learning and the strengthening of public education systems as being for the common good.

As the report notes, today’s education models, largely designed in the industrial era, are struggling to keep pace with contemporary societal needs. The need for an education system that is adaptable and forward-looking is apparent.

This transformation is even more critical in the sub-Saharan region, where educational disparities remain vast.

While global cooperation and partnerships are emphasised as essential in addressing these problems, the onus is on governments and local stakeholders to drive reforms that are contextually relevant and effective.

In the South African context, initiatives such as Execs Back to School serve as a bridge between the global educational vision set out by Unesco and the local actions needed to realise this vision.

On 16 October, I attended the Execs Back to School event at Yeoville Boys’ Primary School, in Johannesburg, where I witnessed the determination and resilience of leaders, teachers and learners.

The event, organised by Citizen Leader Lab in partnership with Sphere Holdings, provides executives with an opportunity to delve deep into the problems confronting South African public schools.

Yeoville Boys’ Primary School, led by principal Lindelani Singo, exemplifies this commitment.

As an alumnus of the Execs Back to School programme, Singo spoke about how the initiative had facilitated his professional growth.

His leadership, coupled with the dedication of the teaching staff, has cultivated a positive learning environment, even in the face of significant socio-economic problems.

Despite it being categorised as a quantile four school, with no fees charged to learners, the infrastructure at Yeoville Boys’ Primary is well-maintained, offering a beacon of hope.

Partnerships with institutions such as the University of the Witwatersrand, the University of Johannesburg and Access World Rugby have provided crucial support, further enhancing the learning experience. This is testament to the transformative potential of public-private partnerships in strengthening education systems.

But the visit to Yeoville Boys’ Primary also illuminated a fundamental flaw in the department of basic education’s quantile system.

Introduced as a tool to address educational inequity post-apartheid, it was designed to allocate resources based on the assets, property value and income per household within a school’s catchment area.

This approach was meant to level the playing field, providing more significant support to schools serving disadvantaged communities. But it has not kept pace with the evolving socio-economic dynamics, especially in urban areas such as Yeoville.

The quantile classification of a school such as Yeoville Boys’ Primary does not accurately reflect the socio-economic realities of its surroundings. Initially assessed when the area was more affluent, the classification has not been updated to consider recent changes, including the influx of low-income families and a rise in informal settlements.

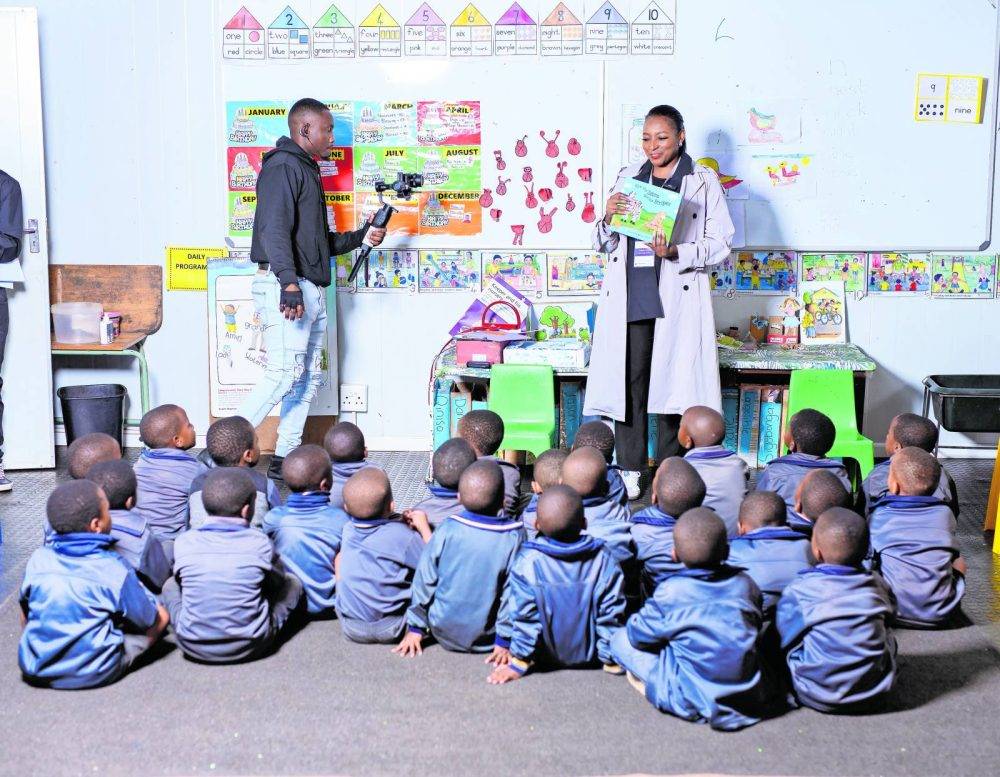

Teach our children well: The Execs Back to School event at Yeoville Boys’ Primary School, in Johannesburg, where principal Lindelani Singo, an alumnus of the programme, spoke (right).

Teach our children well: The Execs Back to School event at Yeoville Boys’ Primary School, in Johannesburg, where principal Lindelani Singo, an alumnus of the programme, spoke (right).

As a result, the school receives less financial support than it needs. This mismatch underscores the rigidity of the quantile system and highlights how it has become an impediment to achieving the very equity it was designed to promote.

To align with the transformative goals in Unesco’s report and to address the gaps in local initiatives such as Execs Back to School, a re-evaluation of the system is needed.

Here are some recommendations for the basic education department:

Regular updates and socio-economic assessments: The quantile system should be revised to incorporate regular assessments of school catchment areas.

By taking into account the changing demographics and economic conditions, the classification can better reflect the actual needs of schools and ensure the equitable distribution of resources.

Dynamic funding models: The static approach to funding allocation does not account for rapid socio-economic changes. Introducing a dynamic model that adjusts funding based on real-time data and needs can help bridge this gap.

For instance, schools in areas experiencing increased migration or economic downturn should receive additional support to manage the influx of learners and the problems that come with it.

Enhanced public-private partnerships: The success of partnerships at Yeoville Boys’ Primary underscores the potential effect of collaborative efforts between the public and private sectors.

The department should facilitate more opportunities for such partnerships, creating a framework that encourages businesses to invest in schools, not only through funding, but also by providing mentorship and infrastructural support.

Site visits: A critical takeaway from the Execs Back to School event was the value of working directly with schools.

By conducting regular site visits, education officials can gain a deeper understanding of the specific problems and needs of schools. This hands-on approach can inform better policymaking and resource allocation, ensuring support is tailored to the unique context of each school.

Focus on lifelong learning and holistic education: In line with Unesco’s emphasis on lifelong learning, policies should be designed to nurture skills beyond traditional academic learning. Incorporating vocational training, digital literacy and life skills into the curriculum can better prepare learners for the complexities of the modern world.

The private sector has a pivotal role to play in this transformation. Initiatives such as Execs Back to School show how business leaders can effectively work with and support public education. Companies have the resources, expertise and networks to drive significant change, whether through funding, skills development programmes or mentorship initiatives.

By investing in education, businesses are not only fulfilling a social responsibility but also contributing to building a skilled and capable future workforce.

The Unesco report’s call for a new social contract in education resonates deeply with the local realities observed at Yeoville Boys’ Primary. Although global frameworks provide a visionary blueprint for change, it is the localised, context-specific interventions that breathe life into them.

To realise this vision, systemic flaws such as those in the quantile system must be addressed.

It is important for the department to recalibrate its policies to better reflect the realities of the communities it serves.

Through targeted reforms and enhanced public-private collaboration, we can move closer to an inclusive and equitable education system that equips every child with the tools needed to thrive in the future.

The resilience of school leaders such as Singo and the eagerness of learners are a reminder of what is at stake: the future of our nation.

Chrissy Dube is the head of governance, insights and analytics at Good Governance Africa.