There has been nothing remarkable about the government of national unity’s first year in office, but the steadying of the ship has been invaluable. Photo: GCIS

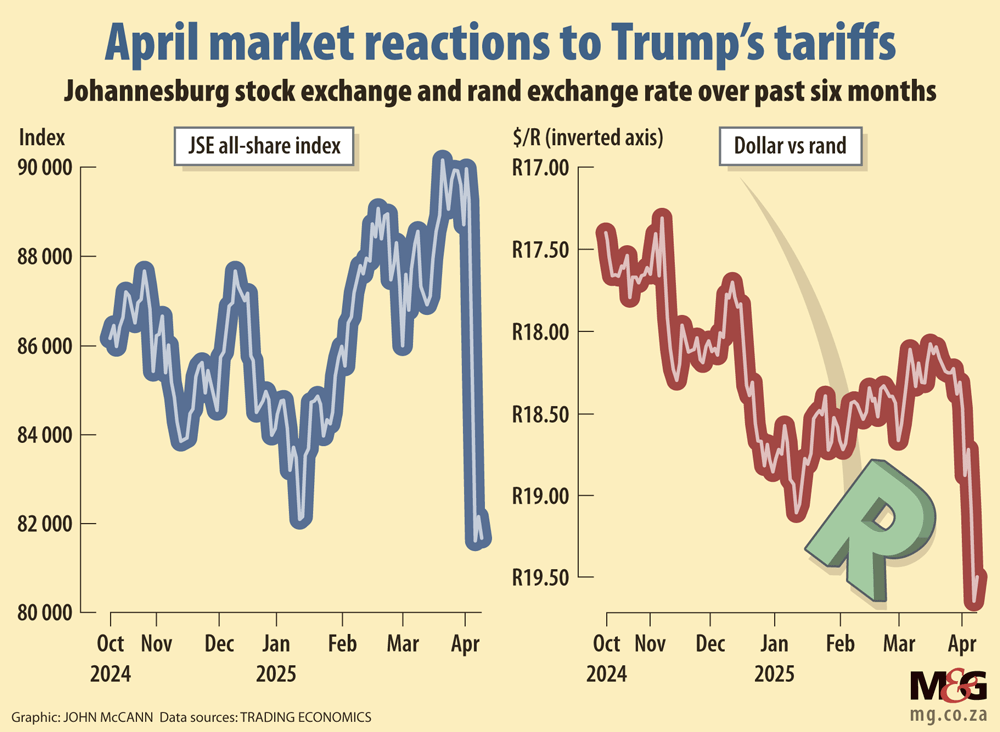

The JSE took a hammering last week. The All-Share Index (ASI) dropped by roughly 4.5% on Thursday alone, wiping out nearly R1 trillion. Hundreds of thousands of South African employees’ pensions are represented in the ASI.

In perspective, a trillion rand is just under half of South Africa’s annual budget for the 2024-25 financial year — an appropriate comparator within which to locate the loss, given that the country’s governing coalition failed to agree on the budget. This rendered the markets more sceptical of the country’s future economic prospects and coincided with the Trump administration announcing a 30% import tariff on goods exported from South Africa.

The tariff imposition signals the likely end of our inclusion in the African Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa), which had granted us preferential (duty-free) access to US markets. It has also tanked the rand, which has fallen below R19 to the US dollar.

These realities are interconnected and devastating. The government of national unity (GNU) — dominated by the ANC (majority with 40% of the total vote) and the DA (minority with 22% of the total vote) — failed to pass a national budget through its combined parliamentary majority. The DA refused to support it on both substantive and procedural grounds.

The ANC then collaborated with other smaller parties to pass the vote through the National Assembly.

This gave no confidence to investors already concerned about losing access to US markets, itself a partial function of how the US perceives South Africa’s foreign policy — another fault line in the fractious governing coalition.

The GNU is not so much a government of national unity as it is a grand coalition, cobbled together out of a combination of goodwill and necessity in the wake of the 29 May election last year. Moderate faction(s) in the ANC agreed that cooperating with the DA would be better for the country than alternative arrangements, and the DA had a chance to demonstrate its governance credentials at the national level.

Foreign and economic policy differences were not explicitly ironed out, though. It is not as if the markets didn’t know this, but we are all creatures of hope, and the statement of intent that governed the coalition seemed to be enough of an institutional bulwark against fracture risk.

But coalition politics at the local level has shown South Africans that budgets are typically the sticking point in making coalitions work for citizens. When budgets don’t pass, services can’t be delivered.

So, what is really behind the fracturing of our grand coalition and why were pre-emptive steps not taken to avoid this governance mess?

Some commentators have blamed narrow party-political interests, accusing party leaders of sacrificing the national interest on the altar of self-advancement. Others have pointed to a lack of real leadership in the GNU. President Cyril Ramaphosa apparently delegated the budget negotiations to his deputy, Paul Mashatile, indicating either passivity on Ramaphosa’s part or that his faction(s) has lost its authority in the party. The reality is more complicated.

First, the ANC sees itself as the chief in the coalition; that it received less than 50% of the popular vote has not really changed how it sees itself. For at least 15 years prior to the 2024 elections, the ANC ran the country like its fiefdom; the Zondo commission state capture report makes this much clear.

The fact that so few politically connected kleptocrats have been prosecuted is a fundamental concern to rating agencies and the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), which has grey-listed us. The FATF was also not convinced that South Africa under ANC rule was doing enough to prevent the country from being used as a conduit for terrorism financing. It did not help that, because of foreign policy incoherence, we looked like Hamas sympathisers after its 7 October 2023 attack on Israel.

These dynamics, including South Africa’s economic and military alliances with Russia and China — which seemed to blow holes in the country’s non-alignment policy — were doings of the ANC before the DA entered into coalition government in June last year.

And the US has made its disdain for our foreign policy clear, especially the genocide case against Israel at the International Court of Justice.

Second, the DA and ANC differ fundamentally on economic policy; the DA is largely in support of a free market, although it does also support a social welfare net; the ANC is not. The ANC has entrenched an oligopolistic market structure in South Africa through policies that favour existing players and big business, just like its apartheid predecessor.

Through governance architecture design flaws, the ANC also enabled the country’s state-owned enterprises to become the primary looting channel for state capture. This, and the extensive red tape that militates against small and medium business growth, raises stagflation risk — rising inflation alongside economic stagnation. We grew at a mere 0.6% last year.

Economic reform should, therefore, have been one of the fundamental agreements underpinning the GNU. A budget would then have been built to reflect this. The DA objected to a VAT increase (especially one that did not adhere to prescribed parliamentary processes) on the grounds that the opportunity costs were too high — VAT hurts the poor, and the middle class is already over-stretched and indebted.

Fundamental reforms to ignite growth are certainly a preferable option. The ANC, though, sought an immediate revenue source to plug the shortfall and wasn’t prepared to take a risk on implementing reforms.

Third, there is always a game of brinkmanship in a coalition of this nature. The two main parties have different support bases, and how each behaves sends a signal to those constituents. Each must be seen to be true to their electoral promises. This is not the same as simply placing party interests ahead of national interests. Rather, it is a matter of defining one’s red lines and then either holding that line or backing down. Every time one backs down, one loses credibility.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

The DA has backed down on rather a lot since joining the coalition. It stuck to its guns on the budget, and made it clear to the ANC that it wouldn’t provide parliamentary support for the VAT increase, both because it reasoned it to be unnecessary and because the right procedures were allegedly not followed. It knew the risk, and that it could be ruinous to both parties (and possibly the country).

In brinkmanship, this is literally the move of taking your opponent to the brink and seeing who blinks first to avoid mutual destruction. The ANC simply bypassed the budget brink by coalescing other parties to circumvent the coalition dynamics. In the process, though, it probably broke the coalition.

The outcome is that while the ANC avoided the budget brink (for now), it did not avoid mutual destruction — both parties will suffer if the country’s economic situation continues to plummet.

Pre-emptive steps could arguably have been taken to avoid this outcome, but it seems as if the DA did not bank on the ANC garnering sufficient support from other parties to avoid the implications of the gridlock between itself and the DA. In the end, the ANC came across as the playground bully.

The DA took a risk to enter the coalition and has arguably been ridden roughshod over on foreign and economic policy; at some stage it was going to have to take a stand and play brinkmanship.

But the mutually destructive outcome is R1 trillion of value gone. And that is probably just the beginning.

Ross Harvey is the chief research officer at Good Governance Africa’s Southern Africa regional office.