Endowed with a third of the world’s supply of them, the continent must push for actions that have the most benefits for its people. (Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images)

At the turn of 2025, the World Bank, the African Development Bank, the African Union and the continent’s governments delivered a bold new initiative titled Mission 300. It aims to reduce Africa’s energy poverty by halving the number of Africans without access to electricity from 600 million to 300 million by 2030.

The chances of realising this goal, especially within this short period, depends on the extent to which the continent takes charge and overcomes external competing interests.

Over time, Africa’s pursuit of climate justice, including a just energy transition, has been hampered by self-interest and the strong positions held by rich countries and billionaires — positions that have prevailed over reason and the common good.

For example, last year’s 29th Conference of Parties (COP29) finally agreed on a paltry $300 billion of climate finance annually by 2035 against the $1.3 trillion per year by 2030 that Majority World countries had pushed for. This was after two weeks of intense negotiations.

Africa has been denied not only access to climate funds but also the technology needed for a green transition, as rich countries delay their own transition, resulting in a lack of structured mechanisms for technological transfer to Majority World countries.

Plans by big oil companies from rich countries, such as ExxonMobil, BP and Total Energies, to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 indicate that they are not treating the need to bring emissions under control with the urgency it deserves.

Similarly, the energy transition frameworks of African countries such as Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Uganda and Zambia indicate that they plan to exit from fossil fuels incrementally, in some cases as late as 2070.

This is due to the inability of African economies to rapidly phase out fossil fuels, given their overreliance on crude oil and coal-based power production; the fragility of their economic performance as well as a global economic order primarily run by rich countries.

Rich countries’ self-interest is evident in the nature of their investment in Majority World countries. For instance, Europe’s biggest energy investment in Africa, a £19 billion gas pipeline from Nigeria to Morocco with the potential to continue into Spain, is seen as a move to potentially replace Russia with Africa as their main source of gas. This investment aligns with the EU’s target to stop importing gas from Russia in 2027, due to the tense relations occasioned by the war in Ukraine.

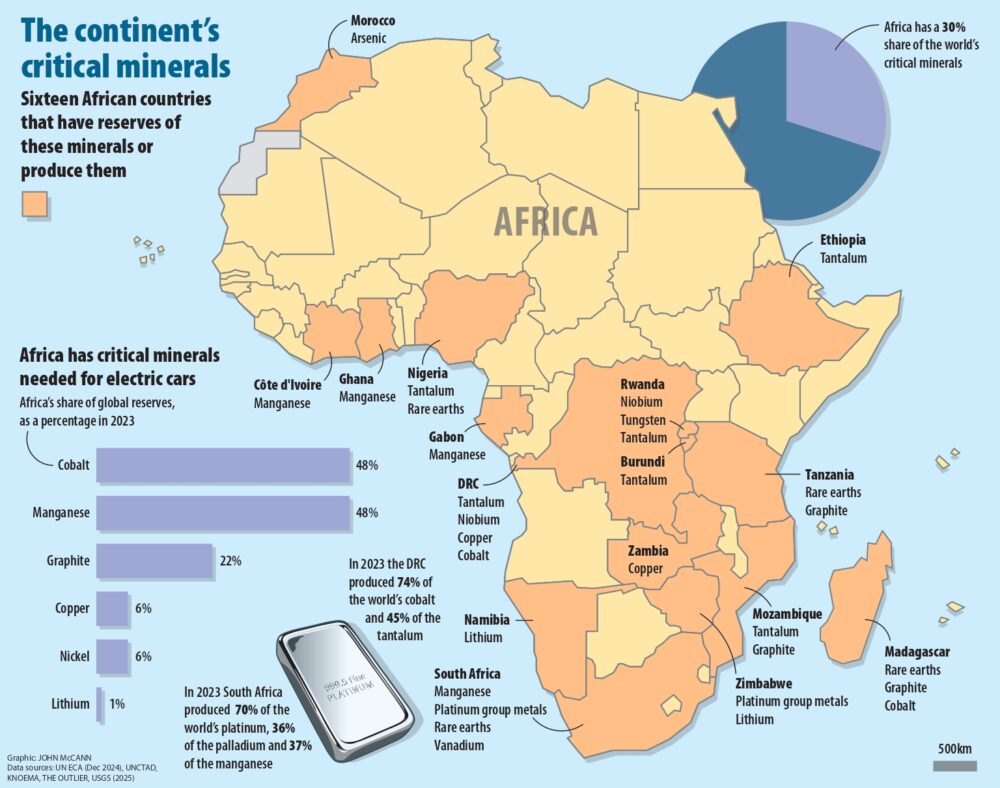

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

The irony of this one-sided partnership between Europe and Africa is contained in Europe’s plan to implement the controversial EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, an initiative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in Europe to to 55% below the 1990 levels by 2030.

The tax implications will have serious ramifications on trade partners such as Africa.

African Development Bank president Akinwumi Adesina has pointed out that such a trade tax could cost Africa a yearly $25 billion in revenue, which is needed to fund critical energy needs and public services.

With the emerging demand for Africa’s critical minerals, estimated at 30% of the global reserve, and a looming second mineral resource boom, Africa has a real opportunity to level the playing field by designing the rules of engagement to facilitate a just, equitable, fair and socially inclusive energy transition.

African leaders and the civil society must not relent in their call for climate justice.

They must continue to demand that the international financial systems urgently address Africa’s debt burden, especially by supporting a long-term measure for a true sovereign debt convention within the UN that will permit poorer countries to take part in decisions on debt treatment.

With the continent spending 34% of revenue on debt repayment, little is left for crucial public services such as health, education and social protection, hence it is not surprising that governments have deprioritised the just energy transition.

During the G20 finance ministers meeting in South Africa in March, African leaders were unanimous in their declaration for debt relief.

Protectionist policies veiled as climate taxes, such as the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, must also be struck out and replaced with an increased flow of grants to finance cleaner energy projects. The continent needs more grants and fewer loans to drive investment in clean energy solutions without recreating neoliberal economic dependency models.

At minimum, the EU should exempt African countries from theCarbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

In addition, the African Petroleum Producers’ Organisation should consider a special-purpose vehicle for fossil-for-critical minerals investments that would tap into the investments pool of the already-capitalised Africa Energy Bank to shore up South-South trade, which is already on the rise, having reached $2.3 trillion in 2023.

This would unlock investment in green minerals and propel Africa swiftly into cleaner fuels, ready to take on the future.

However, it does not negate the importance of African nations taking steps to develop national action plans geared towards implementing the recently launched Africa Green Minerals Strategy developed by the Africa Minerals Development Centre.

With the uncertainty in geopolitical rules of engagement, Oxfam believes it has never been more urgent for Africa to shape a more just future by uniting in its demand for fair exchange to create a more sustainable future for all.

Nkateko Chauke is the acting executive director of Oxfam South Africa and Francis Agbere is the economic justice lead at Oxfam in Africa.