(Graphic: John McCann)

In Setswana, democracy is rendered kgololosego, which translates directly to freedom. Similarly, when academic Hlengiwe Ndlovu asked local historians what democracy means in isiXhosa, respondents used the word inkululeko, which also directly translates as freedom. These translations reflect a deeper, more freedom-orientated expectation of democracy.

Freedom is the condition to which an agent can think, choose and act without undue external coercion or internal constraint. Classic scholarship distinguishes negative liberty — freedom from obstacles — from positive liberty — freedom to pursue chosen ends, enabled by resources and capabilities. When both are realised in practice, we speak of substantive freedom: the lived capacity to turn legal rights into genuine, usable opportunities.

In a study of post-apartheid understandings of democracy, academics Heidi Brooks, Trevor Ngwane and Carin Runciman draw attention to the tensions between grassroots understandings and visions of democracy and that which has been articulated by the ANC.

One of the respondents they interviewed was Baba Nhlapo, of the Kuruman village in the Northern Cape, who remarked: “… we are free, but to our side, we don’t see democracy, we just see bad life. Because they [the ANC] say a better life but to our side it’s a bad life. So, I don’t think they [the ANC are] using the word democracy properly.”

This statement highlights a disjuncture between the promise of democracy and the realities of those on the margins.

Similarly, in her doctoral research on the evolving dynamics of state-society relations in South Africa, with a focus on Duncan Village township and the Buffalo City metropolitan municipality, Ndlovu found that the interactions between state representatives and communities reflect an ongoing struggle for inkululeko — an objective that residents of Duncan Village claim was never achieved with the end of apartheid. As residents in the township noted, the democracy that was achieved is not one they fought for.

This reinforces what philosopher Mogobe Ramose postulates in stating that the principle of democracy is complemented by, and is inextricably linked to, the principle of freedom.

Tracing the disjuncture

The view that democracy is not what was fought for resonates with sentiments long communicated between citizens, activists and liberation leaders. This does not imply a rejection of democracy or a lack of appreciation for political rights. Rather, it highlights a disconnect between formal democratic gains — such as elections and civil liberties — and the substantive freedoms people envisioned: economic justice, land redistribution, dignity and equality.

Ndlovu states that democracy presents a “new” battlefield on which the struggles for the realisation of inkululeko continue to be fought. In other words, South Africans may have achieved democracy, but not the freedom(s) they imagined. The anti-apartheid movement was consistently framed in terms of a “struggle for freedom”, a “liberation struggle” and a “freedom movement” — not simply as a campaign for electoral democracy. For many, the two are not synonymous.

As such, the achievement of democracy without transformation is experienced as an incomplete liberation. The realisation of inkululeko remains a deferred promise.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

Why language is important

The insights from the works cited draw attention to the importance of understanding how democracy is conceptualised through lived experience and historical memory. Language plays a crucial role in this process.

The absence of a direct vernacular equivalent for “democracy” in many South African languages suggests a deeper disconnect between the institutionalisation of democracy and its daily practice, between state and society, between expectations and institutional performance.

This disjuncture reveals that democracy, as introduced in South Africa, was primarily structured around institutions, laws and procedures — not necessarily around redressing the socio-economic injustices entrenched by apartheid. Equally important, it was not structured around the economic, political and ethical maxims that are deeply embedded in the ethical and communal values of ubuntu.

This reality becomes more apparent when considering how many South Africans, particularly in marginalised communities, articulate democracy less in terms of elections and procedures, and more through expectations of dignity, justice and communal accountability.

The gap between how democracy is institutionally framed and how it is lived by citizens reveals a dual dissonance: first, between democracy and substantive freedom, and second, between democratic governance and citizens’ everyday experiences of political life. This divergence is particularly striking in South Africa, where the formal institutional apparatus of democracy coexists with widespread dissatisfaction and disillusionment.

Despite relatively strong scores on governance indicators, South Africa is one of the few countries on the continent where public support for and satisfaction with democracy remains notably low.

It is crucial to avoid equating the decline in support with the wholesale rejection of democracy without interrogating how daily experiences shape democratic perceptions.

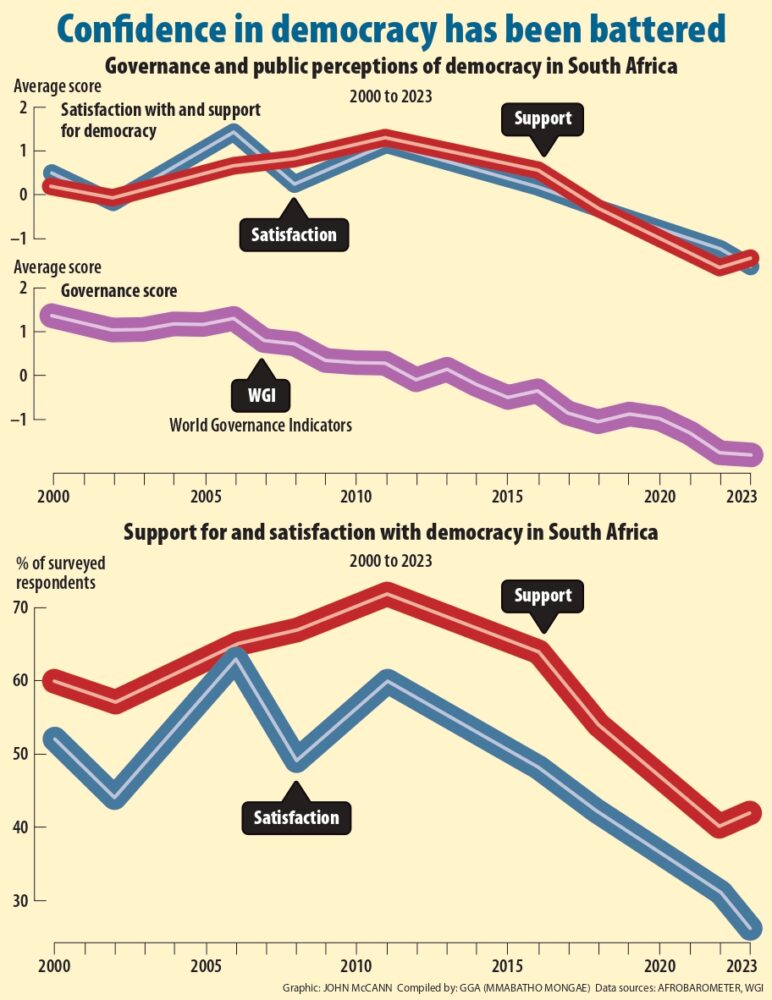

Support for democracy in South Africa remains fragile. From 2000 to 2011, support increased from 60% to 72%. But, from 2011 to 2022, it declined from 72% to 40% before rising to 42% in 2023. This modest recovery coincides with a slight improvement in governance scores during the same period.

As illustrated in the figure, there is a positive correlation between public perceptions of democracy and overall governance quality. Periods of declining governance are generally accompanied by reductions in both satisfaction with and support for democracy. Conversely, modest improvements in governance tend to be met with slight increases in democratic perceptions.

Notably, 2011 marked the highest recorded levels of support for (72%), and satisfaction (60%) with, democracy. But the Worldwide Governance Indicators score remained constant between 2010 and 2011. This divergence may be partly attributed to the 2010 Fifa World Cup, which ushered in a period of extensive infrastructure development and improvements in service delivery — factors that probably enhanced perceptions of state performance. Post-2011, both governance scores and democratic perceptions have been in steady decline.

Furthermore, a long-standing trend persists in which many South Africans are willing to trade democratic processes for material benefits. As early as 2000, 61% of respondents expressed a willingness to forego elections in exchange for jobs, housing and security. This figure has remained relatively consistent across Afrobarometer survey rounds, dipping to 35% in 2002 but resurging thereafter.

According to the 2024 Afrobarometer survey, 85% say that the country is going in the wrong direction. When asked to identify the top issues the government should address, 71% cited unemployment, 26% pointed to electricity and load-shedding, and 21% highlighted corruption. Other concerns included inflation, poverty and crime.

These findings do not reflect a wholesale rejection of democracy, but rather a deep frustration with government performance. This is further evidenced by the fact that across all Afrobarometer surveys, support for democracy has consistently exceeded satisfaction with democracy.

This observation reveals a polity in which intrinsic attachment to democratic rule endures, while instrumental confidence in its ability to deliver is eroding. Furthermore, the findings signify the centrality of socio-economic wellbeing — particularly for black South Africans who remain largely excluded from post-apartheid prosperity — in shaping attitudes toward democracy.

Where to from here?

The term “democracy” originates from the Greek demokratein which consists of two words demos (the people) and kratos (power). If the majority remain disempowered, can we truly claim to live in a democracy? Or do we live in a system of democratic governance that functions without the people? The consequences of this contradiction are already visible: declining voter turnout despite the growing number of political parties, unprecedented unemployment — particularly among the youth —persistent poverty, rising crime and widespread civic disillusionment.

These conditions point to a fragile and increasingly dysfunctional democratic ecosystem.

Addressing South Africa’s deep socio-economic problems and realising the long-standing struggle for inkululeko or kgololosego cannot happen in isolation from how democracy is understood, practiced and institutionalised.

Any genuine democratic project must be grounded not only in the rule of law and free elections but also in the experiences, cultural meanings and expectations of its people. Language, as a carrier of these meanings, must therefore be taken seriously.

A democracy that fails to speak the language of its people — both literally and figuratively — is unlikely to gain their enduring support.

Dr Mmabatho Mongae is the lead analyst in the governance insights and analytics programme at Good Governance Africa.